Geoeconomic fragmentation looms over euro area financial stability

Geoeconomic fragmentation looms over euro area financial stability

0:00 minGeopolitical tensions pose risks to capital flows. Over the past two decades the euro area has deepened its financial ties with countries whose foreign policies are now increasingly at odds with Europe’s own. An escalation of geopolitical tensions can trigger capital outflows from the euro area and strain its external financing. The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) actively monitors and analyses these risks.

Financial exposures to geopolitical risks have increased over time

Geopolitical tensions have economic costs, causing, for example, both international trade and cross-border capital flows to suffer. This is geoeconomic fragmentation. A recent ESM discussion paper examines the implications for the euro area’s external financing.

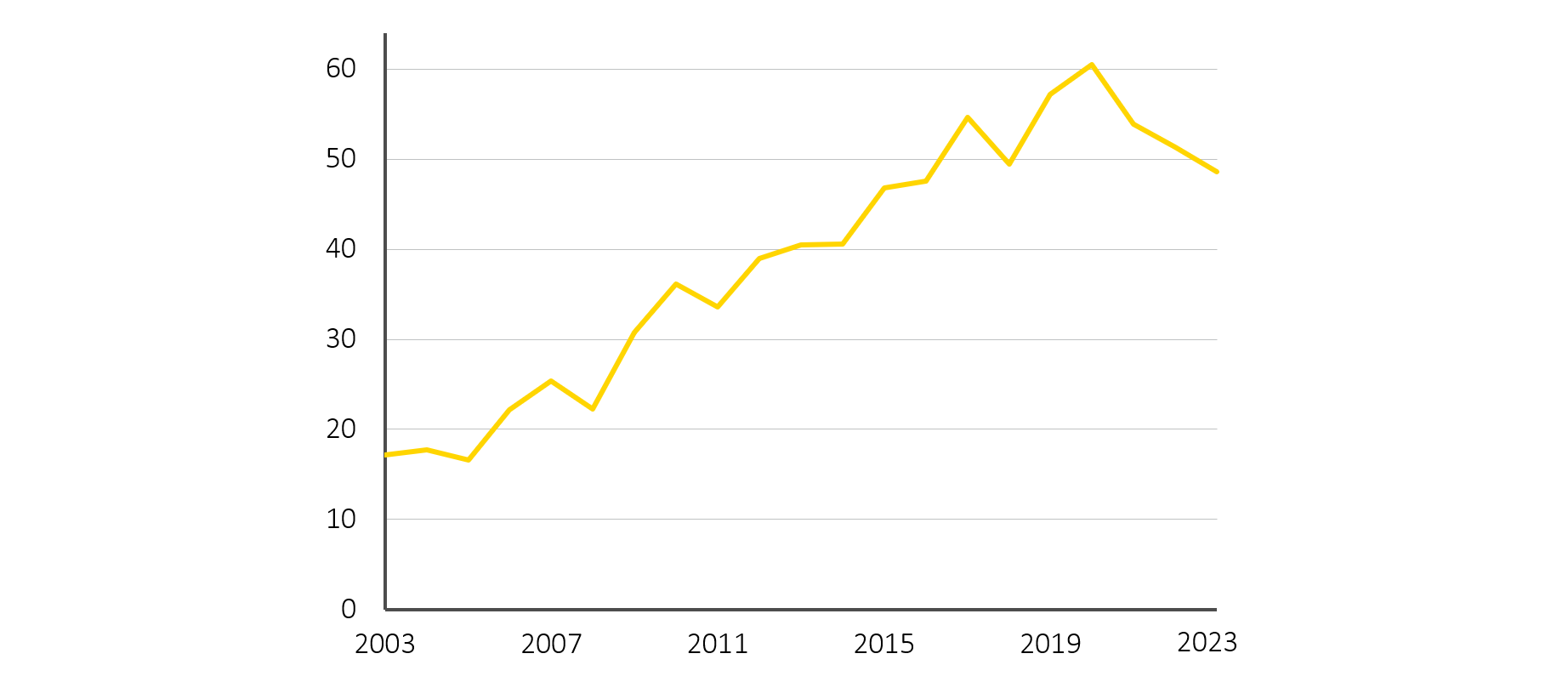

We find that the past two decades have seen an increase in the euro area’s financial exposure to the risk of geoeconomic fragmentation (see Figure 1). The euro area has deepened its financial ties with countries whose foreign policies are now increasingly at odds with Europe’s own, such as China and Russia. Summed across all financial instruments, these positions towards geopolitically distant countries [1] more than doubled since 2008, peaking at 60% of euro area GDP in 2020. Then, by mid-2023 they had fallen below 50% of GDP, indicating ongoing fragmentation.

Figure 1: Euro area’s aggregate financial exposure to fragmentation risk

(2003–2023, % of euro area GDP)

Notes: This figure plots the euro area’s estimated gross direct exposure to financial fragmentation risk. It is computed by weighting bilateral positions with a geopolitical proximity index (countries geopolitically aligned with China receive a weight of 1, neutral ones a weight of 0.5, and others a weight of 0). Gross positions (assets plus liabilities) are normalised by euro area GDP.

Source: ESM calculations based on the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Coordinated Direct Investment Survey and Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey, the Bank for International Settlement (BIS) Locational Banking Statistics, and other complementary data described in the ESM discussion paper

Pockets of vulnerabilities

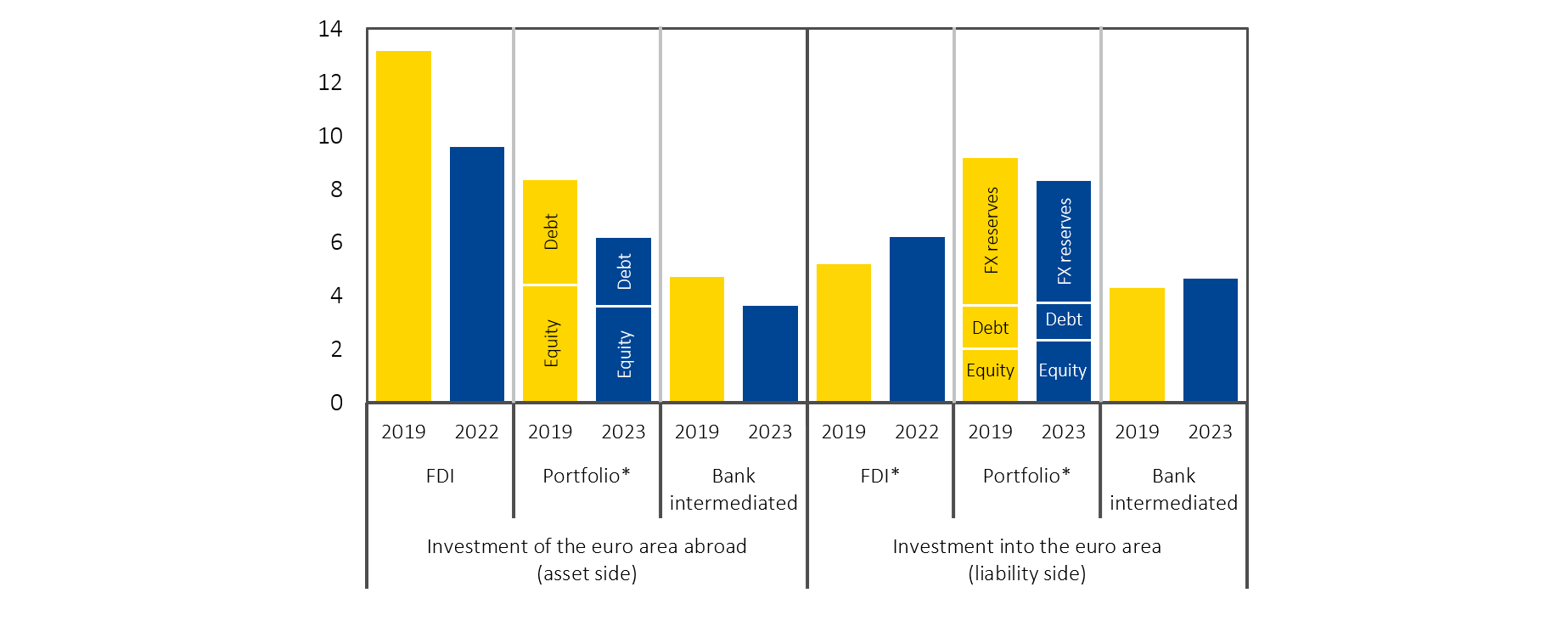

Foreign direct investment (FDI) and portfolio investment exposures to geopolitically distant countries stand out in aggregate (see Figure 2) but vary across euro area member states. [2] Large euro area countries tend to have larger FDI investments in other countries that may be at risk, while smaller economies tend to be mainly recipients of inward FDI. Euro area investors have cut back on their investments in geopolitically distant countries recently, but FDI investments from distant countries into the euro area have been little affected.

Portfolio investments from geopolitically distant countries to euro area securities reach 8.3% of GDP, including a significant portion of sovereign debt held as reserves by foreign central banks. Our estimates suggest that roughly one third of euro area sovereign debt held by non-euro area investors is in the hands of non-politically aligned countries as official reserves, although this figure comes with high uncertainty due to data limitations. [3]

Figure 2: Euro area exposures to geopolitically distant countries

(2019 vs latest, % of euro area GDP)

Notes: This figure focuses on the euro area countries’ investment positions to the group of geopolitically distant countries relative to the size of the euro area economy. *Restated figures, wherein inward FDIs are estimated on an ultimate basis, and portfolio debt liability positions include securities held as reverse assets by foreign central banks (cf, “FX reserves”).

Source: ESM calculations based on the IMF’s Coordinated Direct Investment Survey and Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey, the BIS’s Locational Banking Statistics, and other complementary data described in the ESM discussion paper

Portfolio investments sensitive to geopolitics

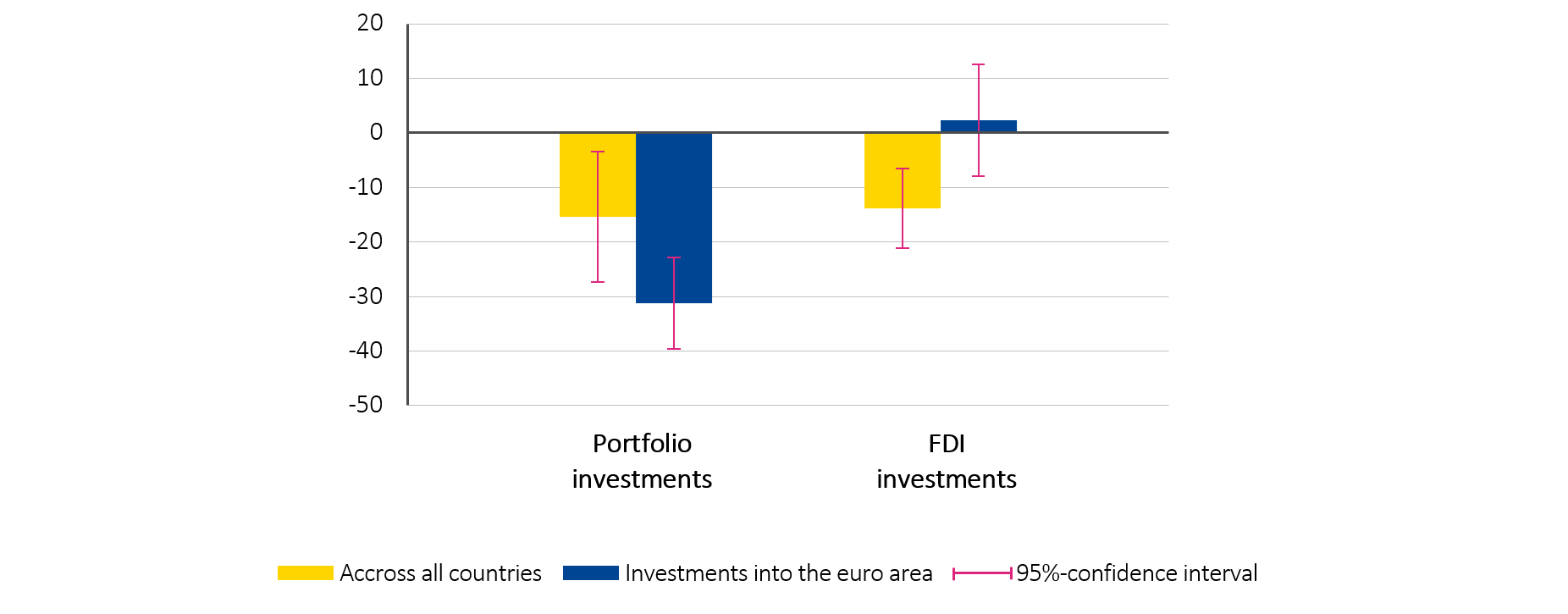

Rising geopolitical tensions strain the euro area’s financial links to other countries. Empirical evidence confirms that investor countries allocate smaller investments to partners with differing foreign policy views. This sensitivity is particularly pronounced for portfolio investments to and from euro area member states (see Figure 3). If geopolitical distance between countries increases, these investments decline. [4] Geopolitical factors can also play a role in the currency composition of foreign exchange reserves. [5]

Figure 3: Impact of geopolitical distance on cross-border investments

(change in a partner’s investment share due to an increase in geopolitical distance, in %)

Notes: This figure plots the estimated percent change in a recipient country’s share of a source country’s cross-border investments in response to one standard deviation increase in geopolitical distance between the two countries. Results are based on gravity-type models applied to bilateral cross-border financial stocks using a large panel of economies from 2005 to 2022.

Source: ESM calculations

Adverse geopolitical events can also impact portfolio flows between the euro area and the rest of the world more broadly. Foreign investors’ behaviour towards the euro area can shift depending on the prevailing level of geopolitical risk.

The euro area is usually seen as safe haven, attracting net portfolio inflows. Typically, when a geopolitical shock hits, euro area investors withdraw from foreign equities, while foreigners increase their purchases of euro area equities, resulting in net equity inflows. Additionally, the search for safety prompts inflows into euro area debt securities, as long as geopolitical risks are generally contained.

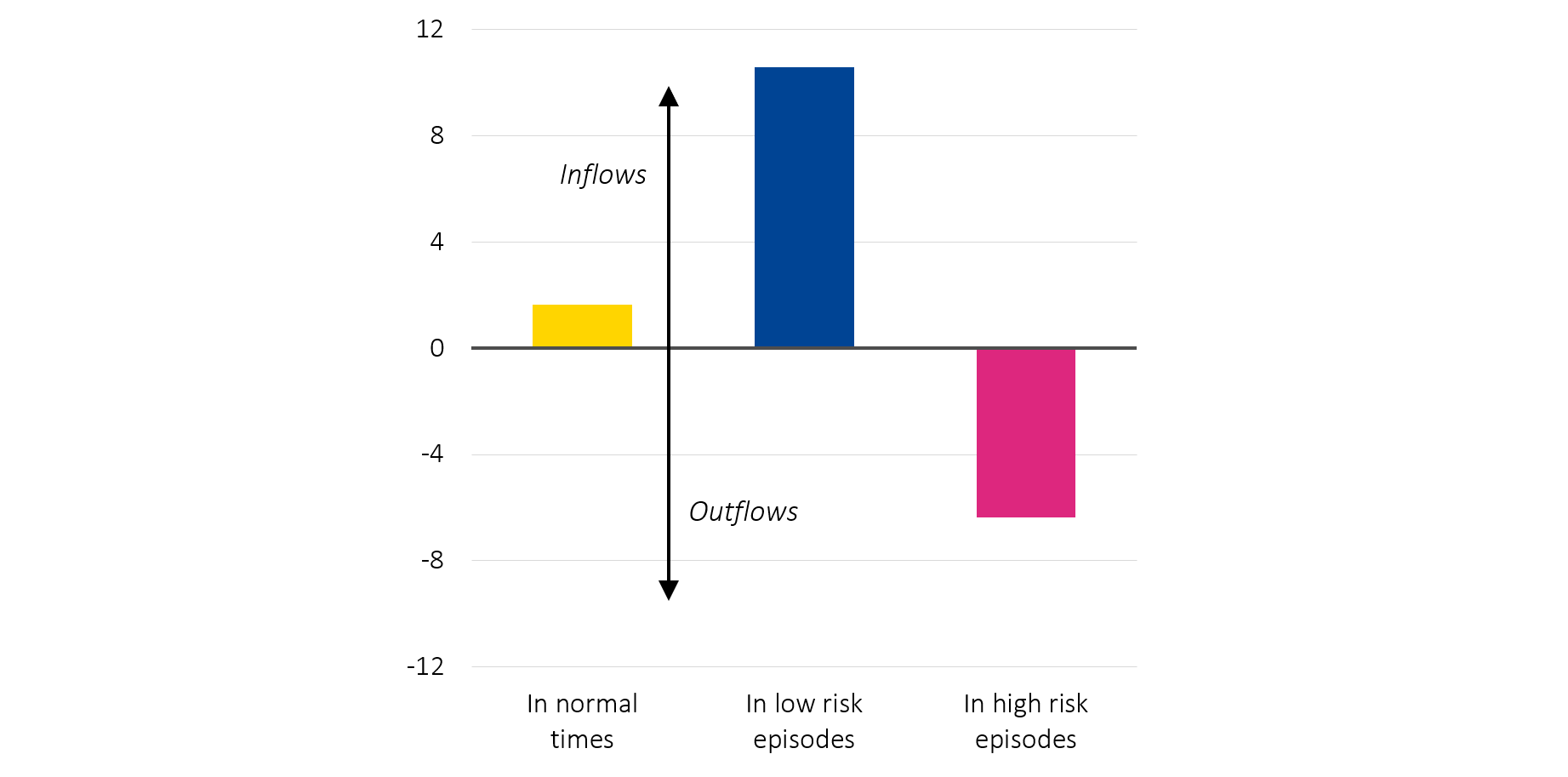

However, portfolio debt inflows become fickle in a geopolitically risky environment. Our analysis suggests that when geopolitical risks are more elevated, shocks can trigger portfolio outflows from the euro area (see Figure 4). This puts further constraints on the euro area’s external financing.

Figure 4: Elevated geopolitical risks can lead to portfolio outflows from the euro area

(impact of a global geopolitical shock on portfolio debt flows into the euro area after six months)

Notes: Median impulse responses to a one standard deviation shock to global geopolitical risk (Caldara and Iacoviello, 2022), based on a Bayesian vector autoregression (BVAR) model with monthly data from April 2000 to December 2023. The figure shows results from a constant-parameter BVAR model (i.e. normal times), and from an endogenous Markov regime-switching BVAR model that detects low/high risk regimes based on the level of the geopolitical risk index. A positive (negative) number indicates net purchases (sales) of euro area instruments by non-euro area investors.

Source: ESM calculations based on Eurostat, Haver analytics, and data from Caldara and Iacoviello (2022). Measuring geopolitical risk. American Economic Review, 112(4), 1194-1225.

Diversification and risk-sharing can help

As geopolitical risks increase, financial shocks to the euro area become more frequent and intense. The euro area’s response should not, however, be isolation, as this would reinforce fragmentation. The euro area stands to lose if globalisation reverses, and global financial markets become fragmented. Financing would become more scarce and costly.

Instead of decoupling, a diversification of the euro area’s global financial linkages can help mitigate financial shocks. Domestically, risk-sharing through the help of the ESM, banking union, and capital markets union would support the euro area’s resilience in the face of today and tomorrow’s increasing global volatility.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Pilar Castrillo, Graciela Schiliuk, and Rolf Strauch for their valuable comments and contributions to this blog post, as well as AMRO colleagues for valuable discussions, and Raquel Calero for the editorial review.

This blog is based on Chapter 3 of the ESM joint discussion paper with AMRO staff, “Geoeconomic fragmentation: Implications for the euro area and ASEAN+3 regions”.

Footnotes

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Authors

Blog manager