Higher interest rates attract investors to euro area sovereign debt but pose challenges for public finances

The recent increase in interest rates has changed the landscape of euro area government debt. While governments must pay higher borrowing rates to finance their deficits, higher bond yields attract investors. Looking at the origin of the new demand for government debt, we ask if this will endure and what the implications of higher borrowing costs are for sovereigns.

Shifts in demand for euro area government debt

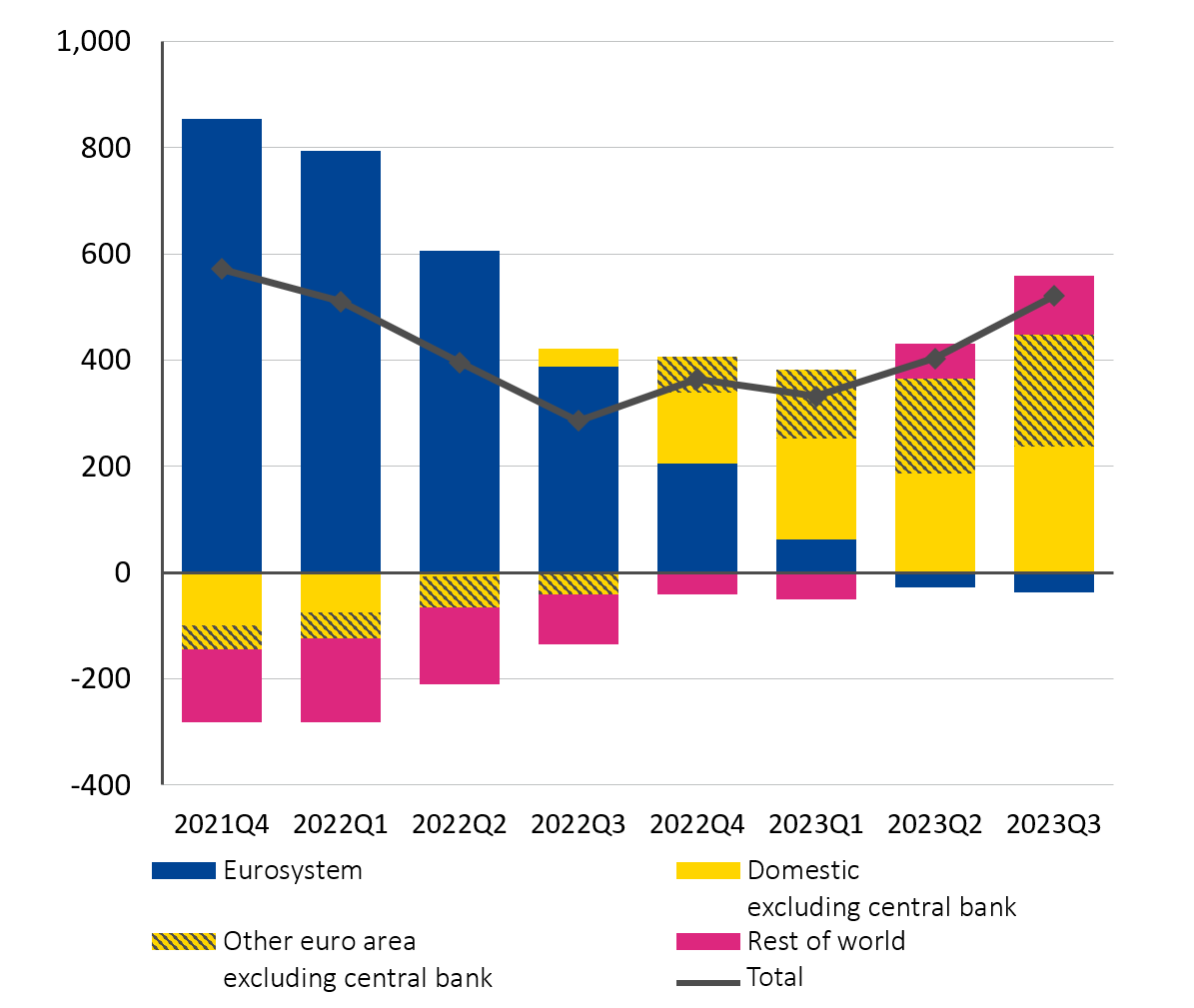

Central banks were key in the demand for sovereign bonds over the past eight years, but that is changing. Around one third of the increase in euro area government debt in 2022 was absorbed by the Eurosystem, which comprises the European Central Bank and the national central banks of the euro area member states. But in 2023 the Eurosystem reduced its holdings in its endeavour to tighten monetary policy, turning into a net seller of sovereign bonds. Consequently, the additional demand from private investors became even more crucial in absorbing the increase in government debt.

Economic resilience and higher yields entice investors

Indeed, higher interest rates and the recent resilience of the euro area economy have attracted more private investors into euro area debt.[1] Investor confidence was also likely supported by enhancements in the European institutional framework, such as the European Commission’s Next Generation EU package to support EU Member States’ recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic .

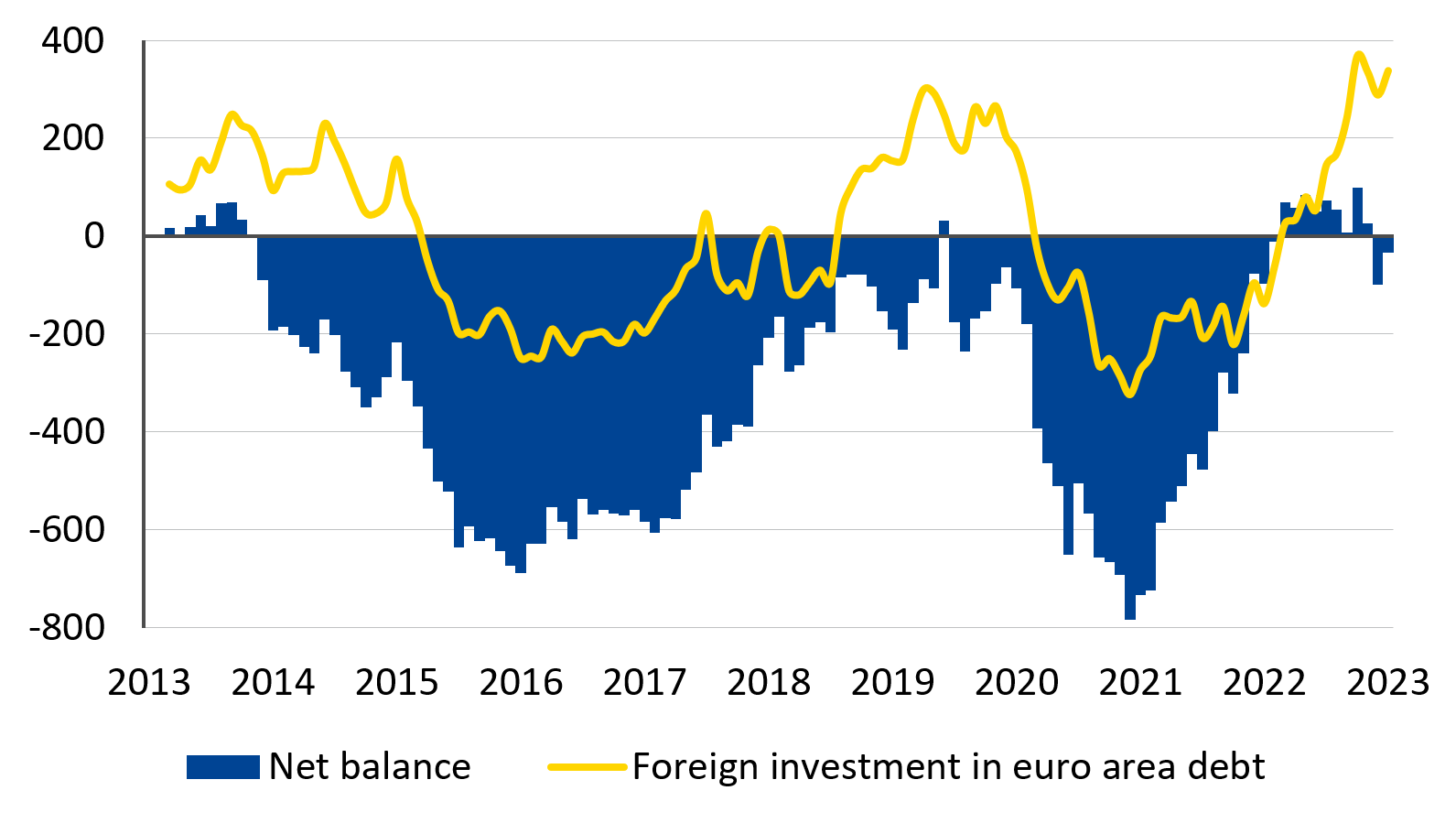

Following years of outflows, foreign investors became net buyers of euro area debt in 2023. The euro area registered the highest influx of foreign investment in euro area debt in the last decade. This helped balance net bond flows even as euro area investors continued to invest abroad (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Foreign investors return to euro area debt

12-month cumulative debt portfolio flows (in € billion)

Note: Net balance is the difference between the purchases of euro area debt by non-residents (“inflows”) and purchases of foreign debt by euro area residents (“outflows”).

Source: ESM calculations based on European Central Bank data

Foreign investors seem to be returning across the four major euro area economies (Germany, France, Italy, and Spain). The four countries combined had attracted nearly €200 billion inflows from outside the euro area into their government debt in the first three quarters of 2023. The uptick in inflows from foreign investors is reflected in the change in composition of euro area government debt holdings. The share of government bonds held by non-residents has increased, although it remains below pre-pandemic levels.

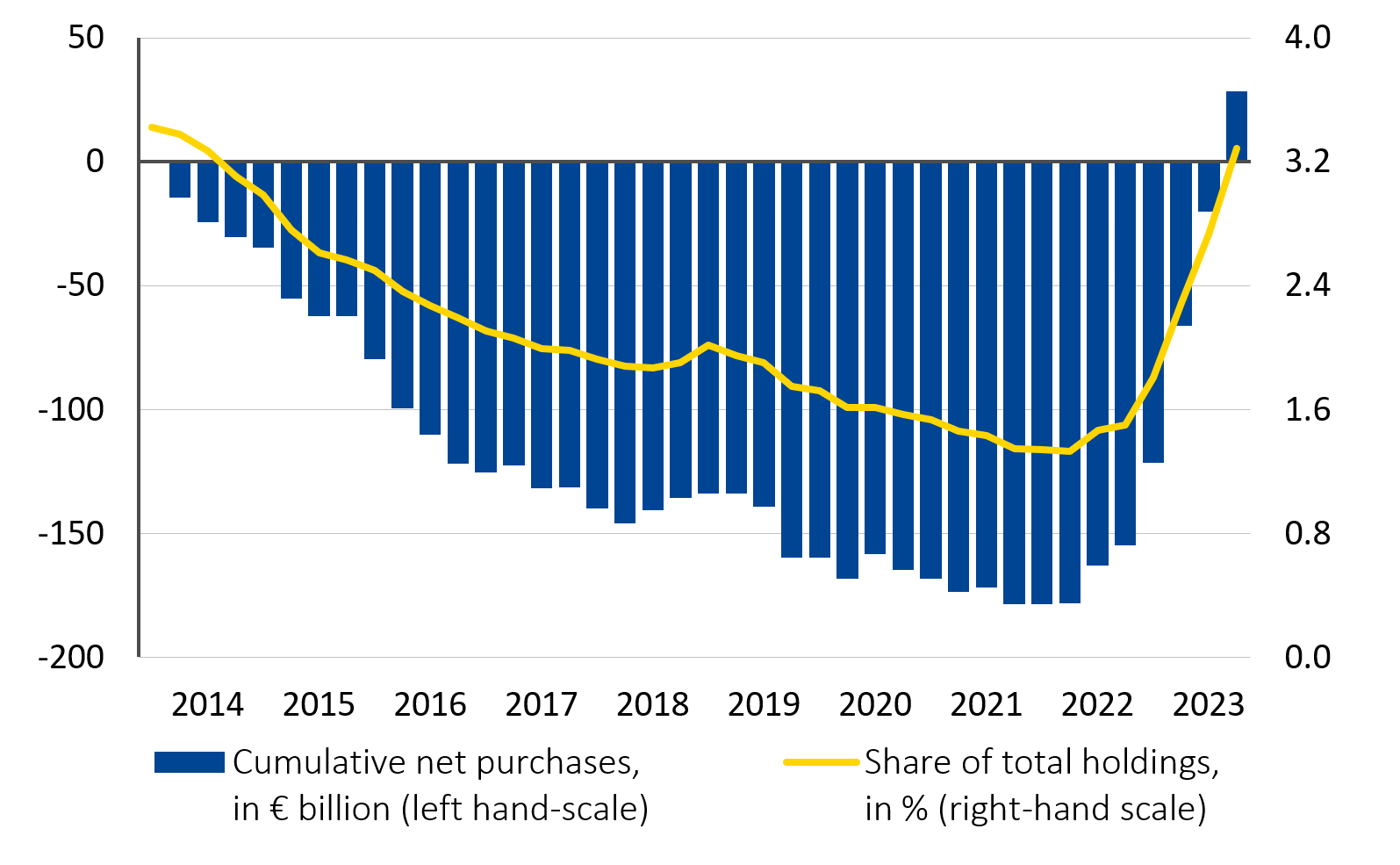

Higher bond yields also attracted euro area households and, to a lesser extent, corporates to invest their savings in government debt. Despite starting at a low base, the share of government debt held by households increased sharply by almost as much as the holdings of foreign investors in the first three quarters of 2023. Debt management offices have been using retail bonds more actively as part of their debt management strategy. Hence, the share of government debt held by households is now as high as it was 10 years ago, at market value (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Households resurface as important buyers

Households’ holdings of government debt securities since 2013

Notes: The chart reports the euro area households’ cumulative sum of net purchases (left-hand scale) since the last quarter of 2013 and their holdings’ share of general government debt securities issued by Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Belgium, Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, Greece, and Finland combined (right-hand scale). Both series end in the third quarter of 2023.

Source: ESM calculations based on European Central Bank data

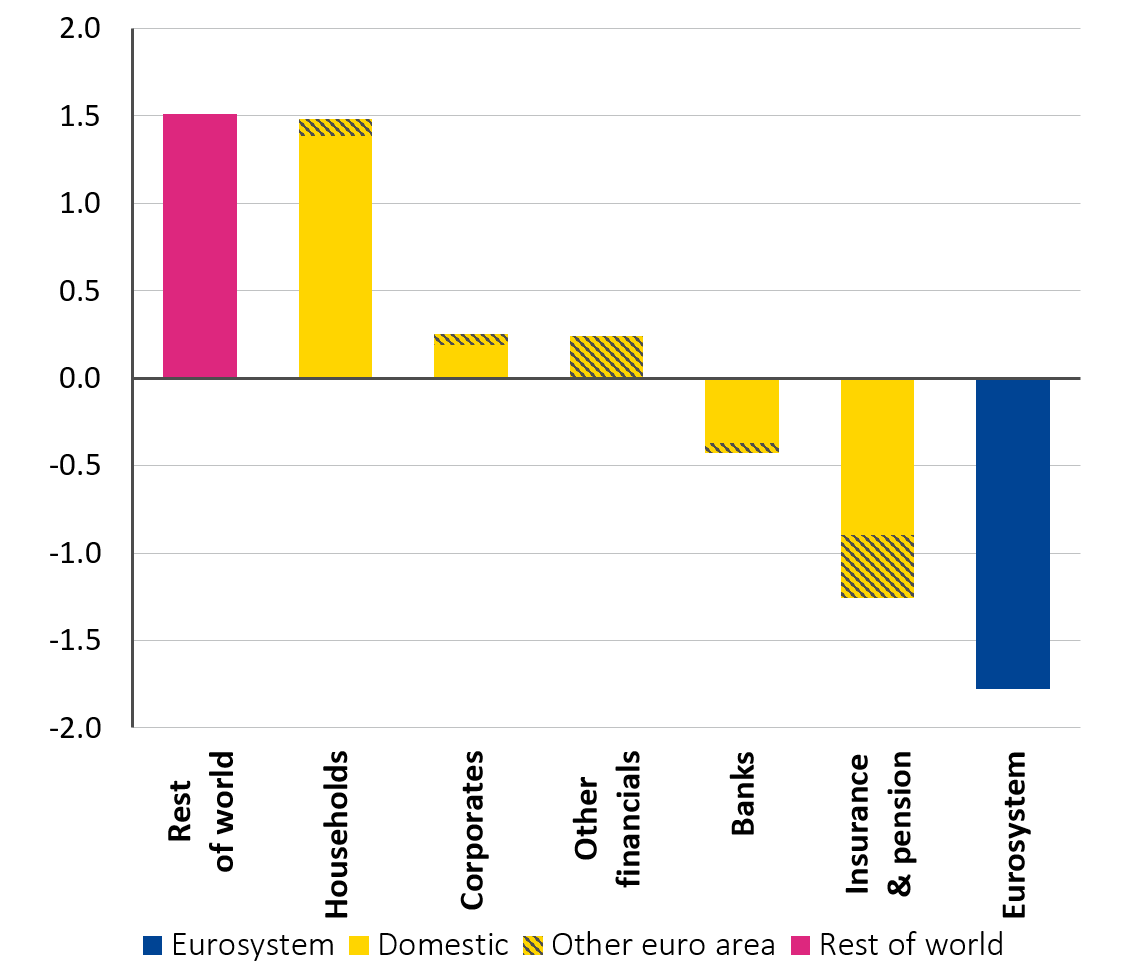

The picture for other domestic investors is more mixed. Asset managers and investment funds within the euro area increased their share of government bond holdings recently, but the share of government debt held by banks, as well as by insurance and pension funds, decreased over the same period, at market value. While the decrease in banks’ share has been relatively modest, the more pronounced decrease in insurers’ holdings may be explained by valuation effects and higher risk-aversion by this sector (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: European Central Bank turned net seller while foreign investors and households fill the gap

3a: Net purchases of government debt securities

(four-quarter sum, in € billion)

Notes: The chart reports the four-quarter sum of net purchases of general government debt securities issued by Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Belgium, Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, Greece, and Finland (combined). Total transactions are decomposed by creditor type, differentiating non-euro area investors (rest of world) from domestic, other euro area investors (both excluding central bank), and the Eurosystem.

Source: ESM calculations based on European Central Bank and Eurostat data

3b: Change in share of government debt holdings

(Q1-Q3/2023, in percentage points)

Note: The chart reports the change in the share of each sector’s holdings (at market valuation) of general government debt securities issued by Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Belgium, Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, Greece, and Finland (combined) between end-2022 and 2023/Q3.

Source: ESM calculations based on European Central Bank and Eurostat data

Bond supply likely to remain elevated, while outlook for demand uncertain

Sovereign financing needs are likely to remain elevated in the coming years. Governments’ budget deficits are expected to shrink somewhat,[2] but spending pressures remain high due to several challenges including climate change, population ageing, and defence expenditure.

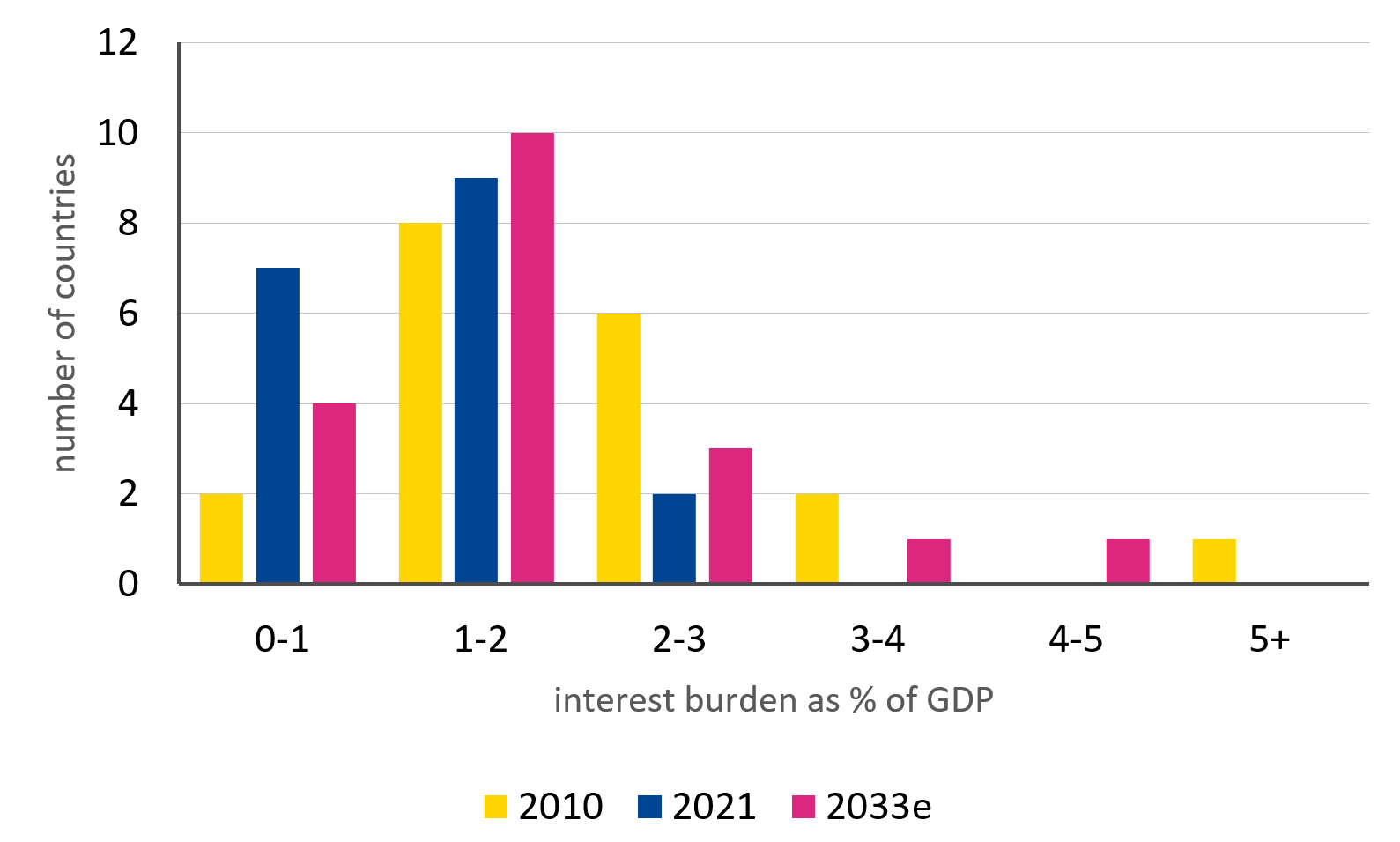

At the same time, the interest burden generated by elevated bond yields and higher borrowing costs will continue to weigh on government budgets long into the future. Euro area debt-servicing costs are expected to rise by around one percentage point of gross domestic product (GDP) over the next 10 years on average, but the increase may be more than two percentage points of GDP for countries with high debt (see Figure 4).

These numbers should be manageable, with some adjustments, if growth performs as per current expectations. However, if the slowdown in economic growth turns out to be more pronounced than expected, investors’ risk appetite could wane, and the risk of differentiation across member states and fragmentation could resurface.

Figure 4: Member states’ interest burden will diverge subject to their debt level

Distribution of euro area member states by interest burden on market debt

Notes: For 2033e, the calculation is based on market forward rates as of 9 January 2024, assuming unchanged debt maturity composition. Maturing debt is rolled over at the forward rates of the average maturity of the portfolio. This mechanical exercise assumes that the primary fiscal balance (before interest payments) is zero, i.e. no additional deficit or debt repayment.

Source: ESM calculations based on European Central Bank, Eurostat, and Bloomberg data

As the Eurosystem gradually stops reinvesting the proceeds from its maturing bonds, governments will need to raise more financing from private investors. Overall, the supply of government bonds to be absorbed by financial markets is set to increase in the coming years, based on projected fiscal developments[3] and the European Central Bank’s guidance for its balance sheet reduction.

The outlook for demand from foreign investors is uncertain and may be subject to swings in risk appetite. As central banks globally continue to reduce their government bond holdings for monetary policy purposes, excess liquidity is shrinking, investors may become more selective, and governments might find it more difficult to finance their debt – even at higher rates. Spillovers from US Treasury markets can also affect European bond markets. According to the latest International Monetary Fund forecast, the US fiscal deficit is expected to remain above 7% of GDP in 2024, generating large financing needs and bond issuance, while the US Federal Reserve’s balance sheet reduction also adds supply to markets.

Uncertainty about the economic and market outlook may lower investors’ absorption capacity. Recent large swings in bond yields, both in the US and Europe, show elevated financial market uncertainty. Bond future options are pricing a 5% chance that Germany’s 10-year government bond yields may be below 1.7% or above 2.6% within 45 days, respectively.[4] Such wide uncertainty can lower investors’ risk appetite.

Domestic household and corporate holdings of European government debt may appear more stable than the foreign and professional investor holdings but are potentially open to higher refinancing risks for governments given their typically shorter maturity debt. In some countries, the room for increased household holdings may be limited given the already sharp increase in recent years. The size and usage of retail funding may change as issuers review their funding instruments. It remains an open question if the usage of retail products will remain such a prominent part of issuers’ toolkit in the coming years.

A credible fiscal outlook and commitment to reform can anchor market expectations

In the face of large market financing needs, a credible fiscal and growth strategy can help sustain investors’ confidence.

The adherence to Europe’s reformed economic governance framework and commitment to fiscal prudence at the national level remain essential. The implementation of national recovery and resilience plans is also crucial to raise competitiveness, productivity, and long-term growth.

A comprehensive strategy can ensure fiscal sustainability and anchor market expectations about the longer-term outlook.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jürgen Klaus, Marco Onofri and Elisabetta Vangelista for valuable discussions and contributions to this blog post, and Marialena Athanasopoulou, Raquel Calero, and Pilar Castrillo for the editorial review.

Footnotes

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Authors

Blog manager