Euronomics: Fragmentation or convergence? Charting the euro area’s economic future

Euronomics: Fragmentation or convergence? Charting the euro area’s economic future

0:00 minAddressing policy divergence is crucial to combatting economic fragmentation and to setting the euro area up for long-term stability and prosperity. This requires strategically allocating responsibilities between European Union (EU) and national levels, focusing on national reforms and efficient EU-level provision of critical public goods.

Policy divergence risks a widening economic gap

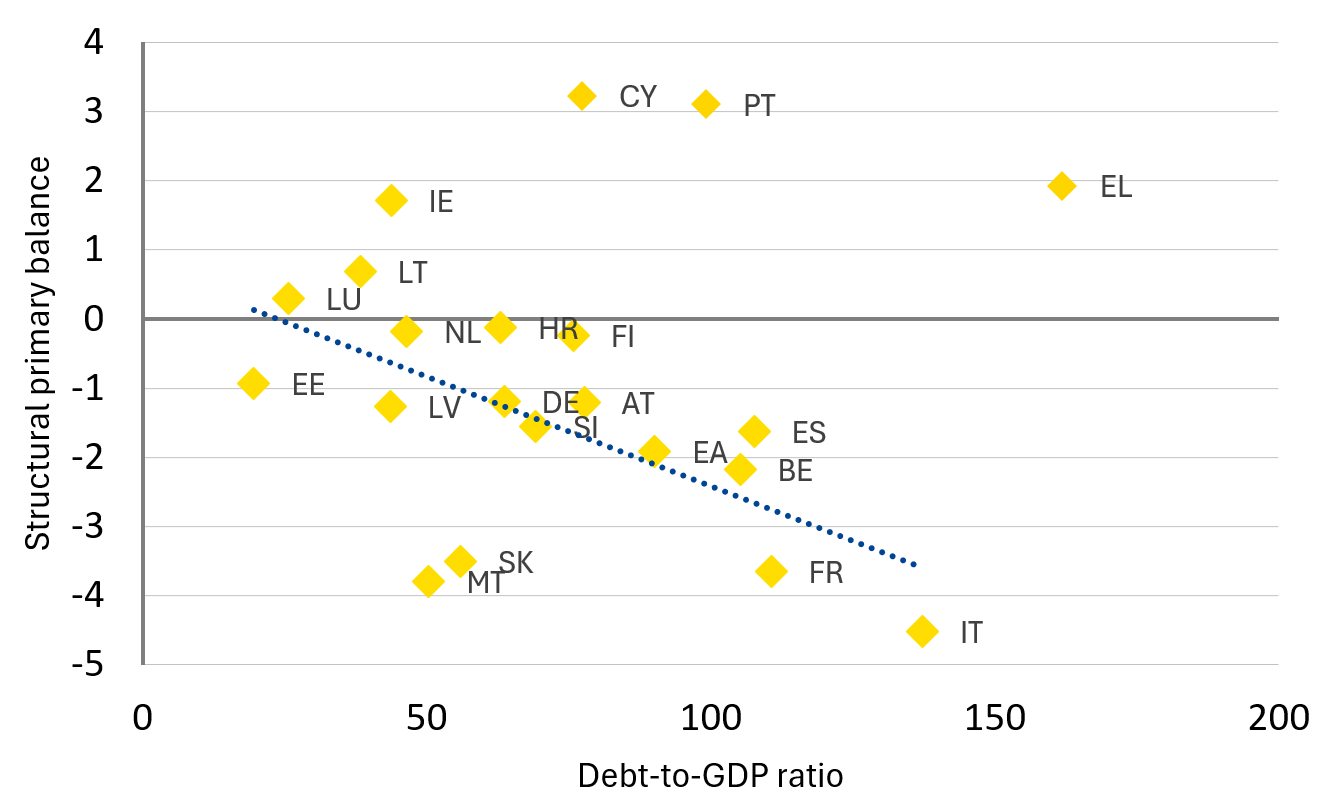

Fiscal space varies strongly across euro area member states, with higher debt usually associated with weaker fiscal positions (see Figure 1). For countries with higher debt, the fiscal adjustments required under the EU’s new fiscal framework can be demanding, bringing the risk of fiscal fatigue and increased shortfalls if the proper policy mix is not found.

Figure 1: Public debt and weaker fiscal positions go hand in hand

2023

(in % of gross domestic product (GDP))

Source: European Commission

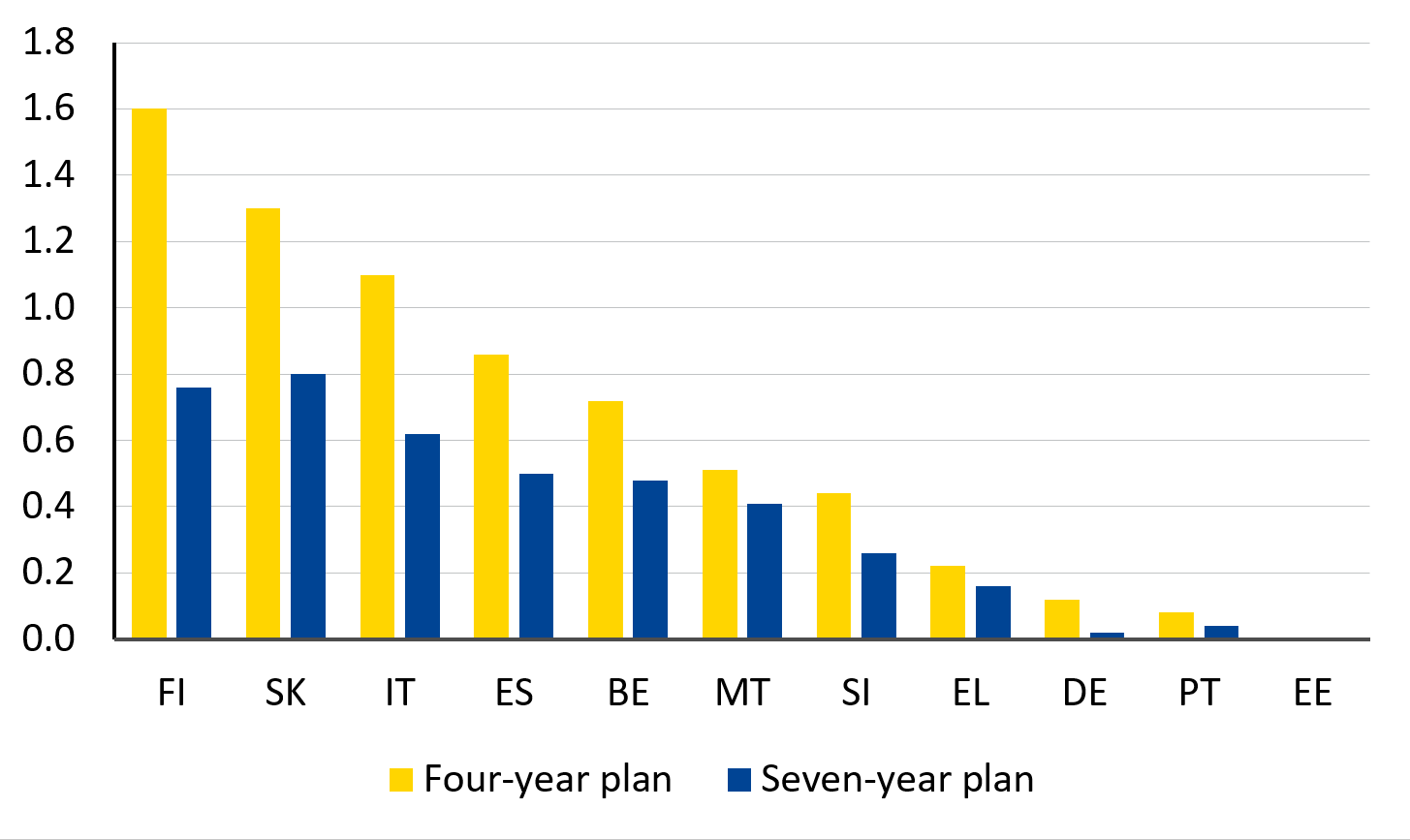

In the past, fiscal consolidation policies often deteriorated the quality of public finances, regularly undermining productive investment. [1] This was especially true for countries already lagging in innovation. The adjustments expected under the EU’s reformed economic governance framework (see Figure 2) could exacerbate things if countries follow past patterns and productive investment suffers from inadequate consolidation design.

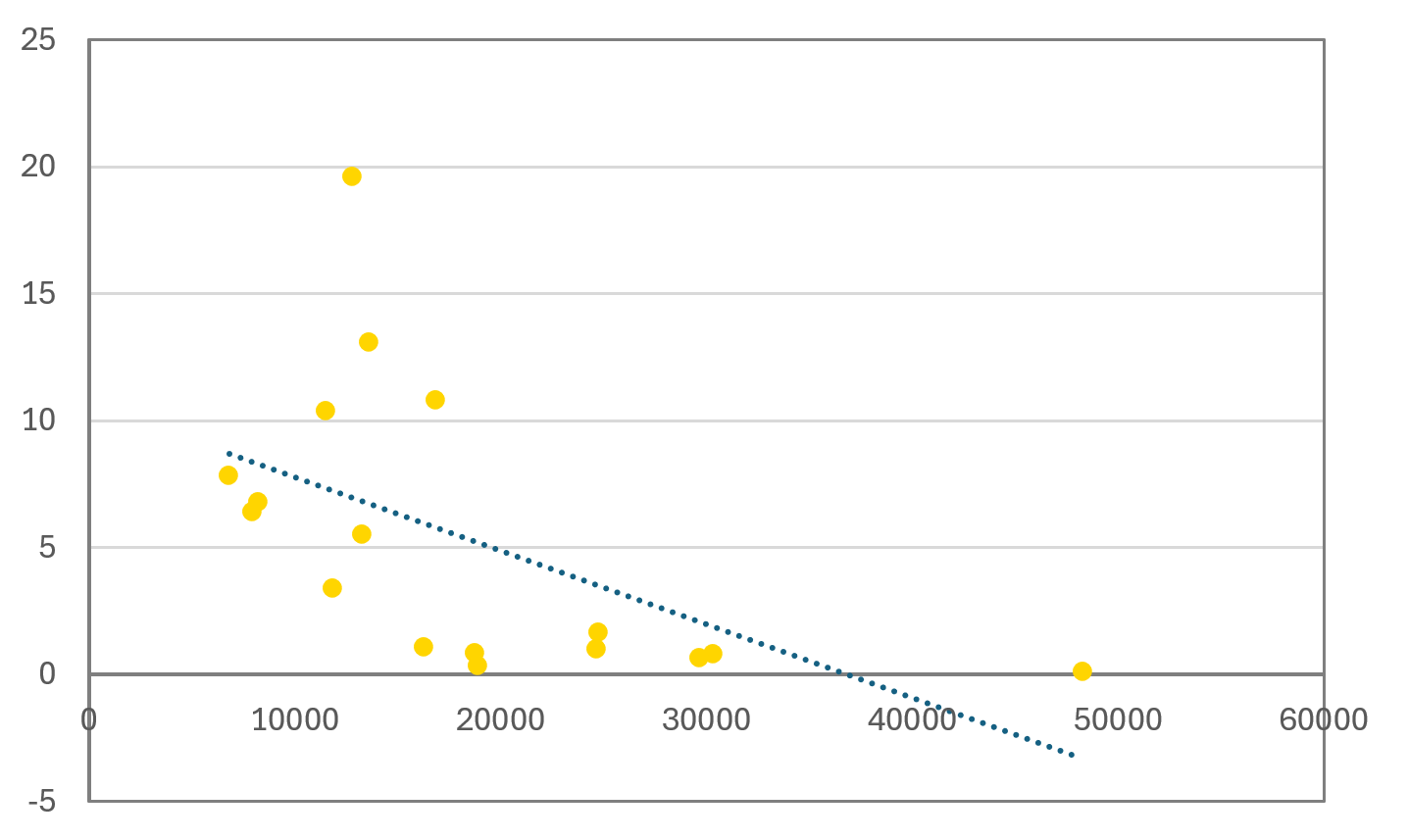

The Next Generation EU recovery fund has been a powerful tool for promoting convergence, helping level out differences in the capital stock of countries shaping their productive bases (see Figure 3). But its 2026 end-of-operation date will remove this crucial mechanism.

These factors place countries at different starting positions to address the long-term challenges that carry the critical risk of widening economic disparities within the EU.

Figure 2: Budgetary consolidation needs under the new fiscal framework vary significantly

(annual averages, in % of GDP)

Source: European Commission

Figure 3: Total recover and resilience facility-funded public expenditure and per capita public capital stock

(x-axis in €, 2019; y-axis in % of 2019 GDP)

Source: European Commission and International Monetary Fund

Increasing pressure on public finances

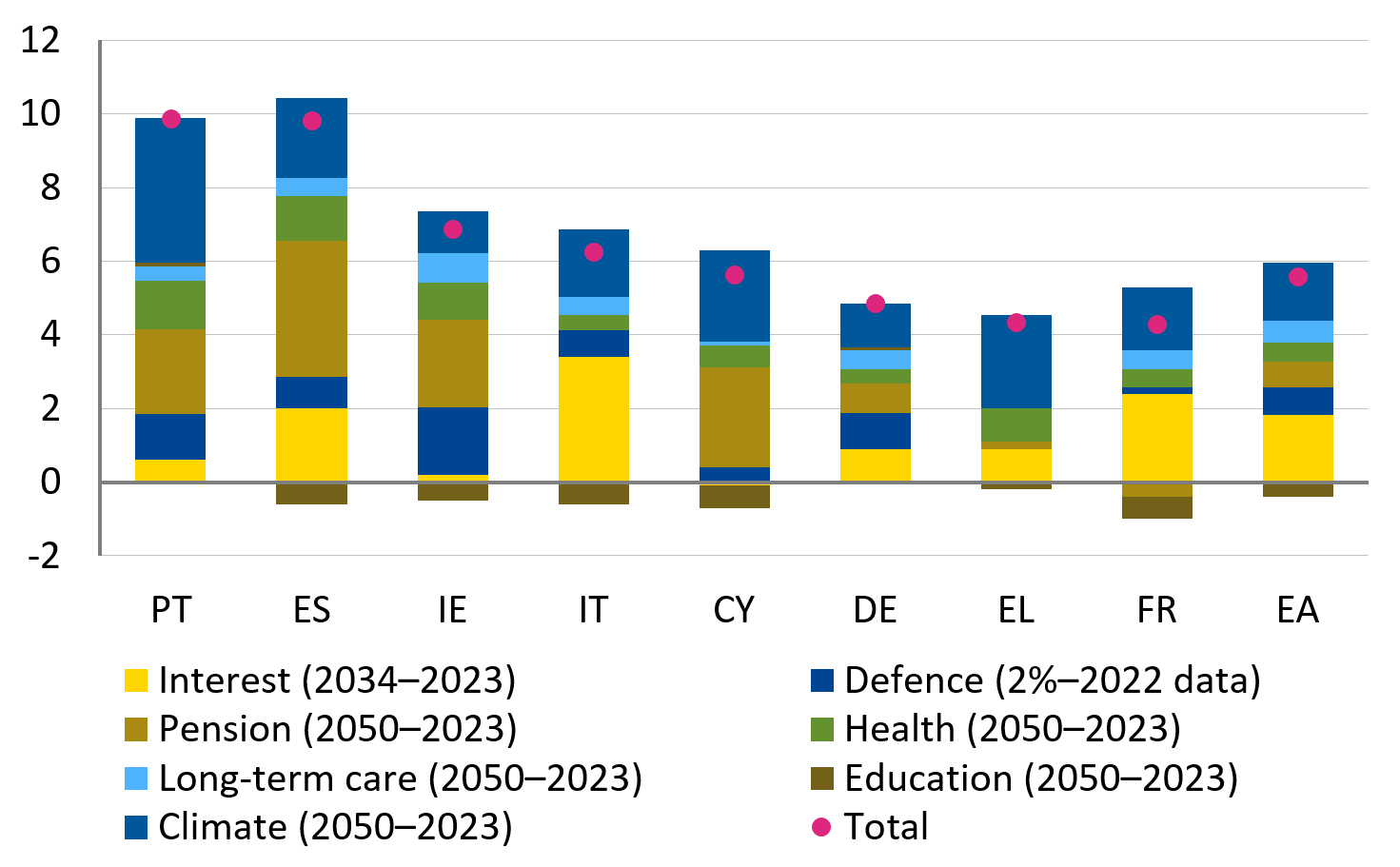

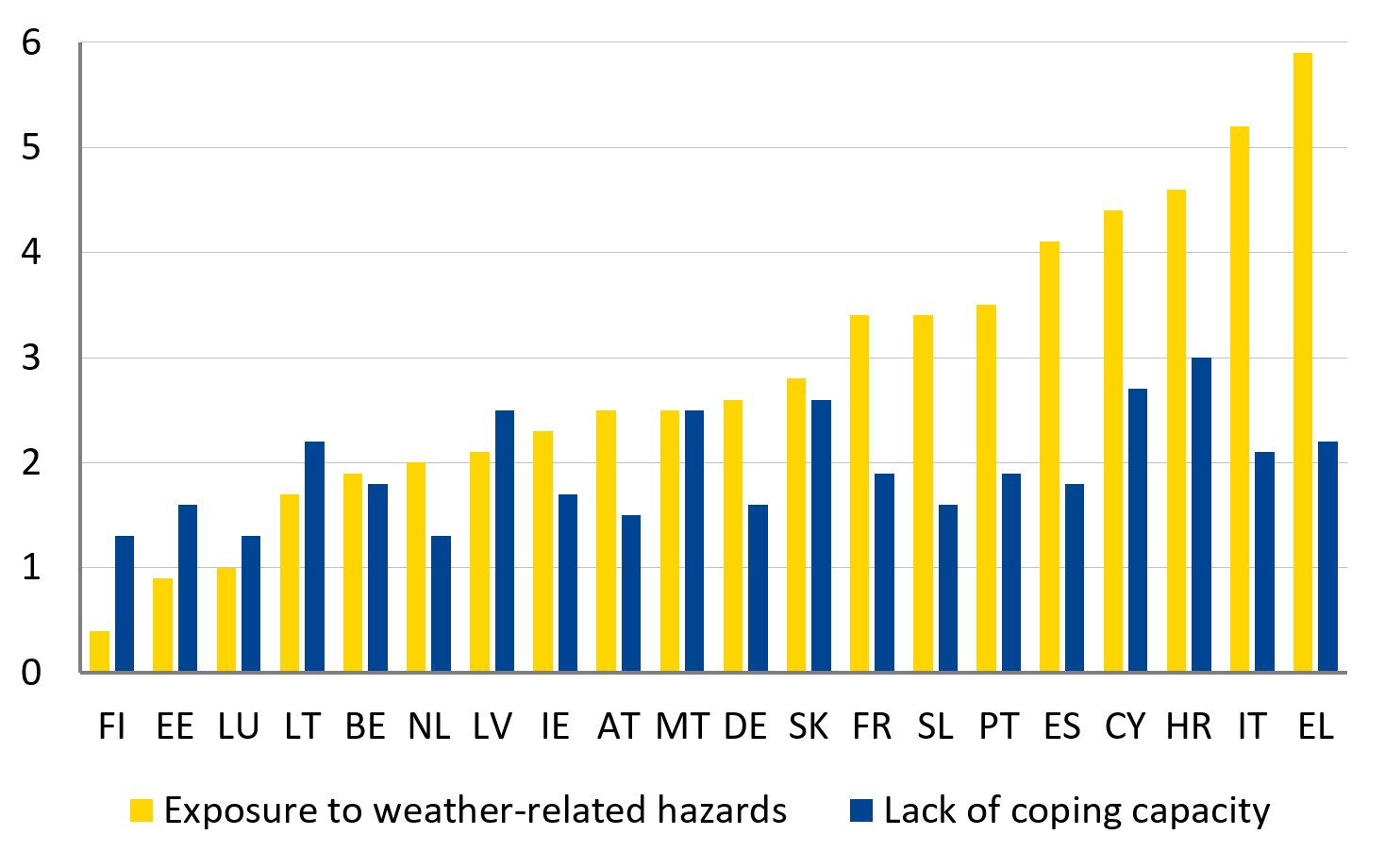

Differences in the currently available fiscal space are aggravated by varying scales of long-term budgetary pressures and economic structures. These pressures differ due to countries’ different exposure to demographics, climate issues, and security risks (see Figure 4). For example, Mediterranean countries, more vulnerable to extreme weather events (see Figure 5), will need targeted (and often costly) adaptation strategies, whereas northern countries may focus on sustainable practices in a more temperate climate. Security risks also differ, with countries bordering conflict zones facing different geopolitical challenges compared to those geographically further away, leading to diverse defence spending needs and, possibly, strategic priorities.

Figure 5: Significant exposure to climate change in the Mediterranean

(INFORM risk index, 10 = worst)

Source: European Commission

Similarly, developing common European objectives has different bearings on countries. For example, differences in network infrastructure imply very different investment needs for the development of a fully integrated European energy market, as some countries lag in increasing their share of renewable energy and improving energy efficiency.

On top of these elements driving divergence, financial markets may amplify the situation when they start focusing on more demanding financing requirements and weaker economic performance. Market financing for some countries could become more severely affected and costly.

Efficient division of labour can help provide European public goods

Addressing these multifaced sources of fragmentation risks requires careful consideration of the appropriate division of labour between the EU level and national levels. Member States indeed do have important responsibilities in conducting reforms and gearing up their economies for long-term challenges. That can, among other things, entail pension reforms and the development of private pension systems to address fiscal pressures and finance investments in the economic transition.

The EU has historically provided public goods mostly through its regulatory functions. This is particularly the case for the single market and for external trade relationships. This area remains crucial to further the EU’s development, growth, and competitiveness agenda – points convincingly elucidated in the Mario Draghi and Enrico Letta reports.[2] In addition, the implementation of fiscal rules and their monitoring help in guaranteeing fiscal sustainability.

Fiscal powers remain decentralised, and the EU has only a limited budget to provide itself public goods. The strategic challenges posed by a fragmented and less friendly geopolitical environment calls for rethinking the pooling of national resources at the European level to promote growth effectively and efficiently in European countries.

Currently, the emphasis is shifting towards EU public goods that may require large investments in physical, human, and digital capital. Draghi’s call for refocusing the EU’s financial resources on jointly agreed strategic projects and objectives, where the EU can bring the most added value, should be seen in this context.[3]

There are two considerations for European centralisation:

- Presence of economies of scale: If the provision of goods at the European level would improve efficiency and reduce costs.

- Externalities: If single EU Member States do not consider the needs of fellow Member States or the impact of its action on them, this leads to ineffective, suboptimal outcomes.

Several policy areas could benefit from being financed at the EU or euro area level. For example, defence, energy and climate-related infrastructure, digital security, the protection against health catastrophes, and macroeconomic stabilisation.

I highlight three specific policy areas, which share the characteristics of scale effects and externalities, that are particularly important for euro area competitiveness and resilience and are suitable for centralised provision:

- High research and development spillovers: Centralised provision would create positive knowledge spillovers, helping boost growth across all EU Member States. The spillovers triggered by centralised provision of technological progress will help catalyse private investment. Centralised provision will also allow all countries to catch-up and advance their technology frontiers, thus simultaneously enhancing resilience and competitiveness.

- Investment in network externalities and cost-saving joint provision of supplies: Network effects emerge from common digital infrastructure or cross-border green energy projects. Common purchasing of critical raw materials and security and defence supplies, and the management of common borders, add to common resilience and can exploit market power and yield direct cost savings.

- Macroeconomic stabilisation: Economic vulnerabilities and financial stability risks carry strong externalities. Having the proper backing to ensure financial stability and support long-term macroeconomic stability, especially in the case of large and externally induced shocks, is particularly important for an economic region like the euro area with one single monetary policy. Completing the financial backbone of banking union would similarly address spillover risks.

Future policy framework priorities

The European institutional infrastructure has evolved often in response to crises. The current challenge is that further institutional development is needed in the presence of a “slow burning crisis” emerging from the lack of competitiveness, geoeconomic fragmentation, and challenges stemming from climate change. Failure to address these issues would imply lack of growth, less resilience, and further fragmentation. An adequate European financial infrastructure can be more cost efficient than individual country action in addressing these challenges and can benefit all countries.

To build such an efficient backbone, it is best to first make good use of existing resources.

The Draghi report clearly points to upcoming discussions for the 2028–2034 EU budget. Now is a good moment to rethink EU functions and their financing to help tackle the different starting positions among Member States. Whenever possible, these funds should complement private funding and catalyse private investment.

Given the magnitude of the challenges ahead, enlarging the pool of EU resources – financed with contributions or own resources – should remain an option if it helps reduce costs at the aggregate level and avoids permanent transfer schemes. Any debt issued under such schemes would eventually be smaller than uncoordinated financing by countries at the national level.

In addition, financing from the ESM could also be considered to address future financial stability challenges. This could further contribute to reducing risks of divergence due to economic shocks and potential financial instability. The ratification of the ESM Treaty and a discussion on the adjustment of its toolbox are steps in this direction.

As we move forward, it is crucial that policymakers, both at the EU and national levels, embrace the vision of a more integrated and strategically aligned Europe. Only through such concerted action can we hope to address the threat of economic divergence and build a stronger, more unified Europe prepared for the challenges that lie ahead.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Marialena Athanasopoulou, Giovanni Callegari, Robert Kraemer for the valuable discussions and contributions to this blog post, Raquel Calero for the editorial review and Peter Lindmark for the graphics.

Footnotes

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Author

Blog manager