Euronomics: Financial buffers and risks during the current credit tightening

The euro area economy and the financial system have proven resilient amidst the energy price crisis and inflation. But economic growth is slowing, and the short-term costs of monetary policy tightening are becoming apparent with the increased constraint on both borrowing and lending. With future financial stability in mind, it is time to examine the capacity of households, firms, and financial institutions to weather the challenges of credit tightening. For governments, as the available fiscal space tightens, prudent policies are needed to maintain market trust.

The cost of fighting inflation is increasingly apparent

Drastic adjustments to monetary policy after an extended period of low interest rates can increase financial stability risks, such as elevated market volatility and liquidity mismatches, which resulted in the eventual failure of some banks earlier this year. We have discussed these risks in a previous blog. These events, among others, were triggered by market surprise about the speed and size of the monetary policy reaction in Europe, the US, and other advanced economies.

Now the euro area will face tighter borrowing conditions, possibly for longer than initially anticipated. Following a period of historically low interest rates, companies, households, and governments are again facing higher borrowing costs.

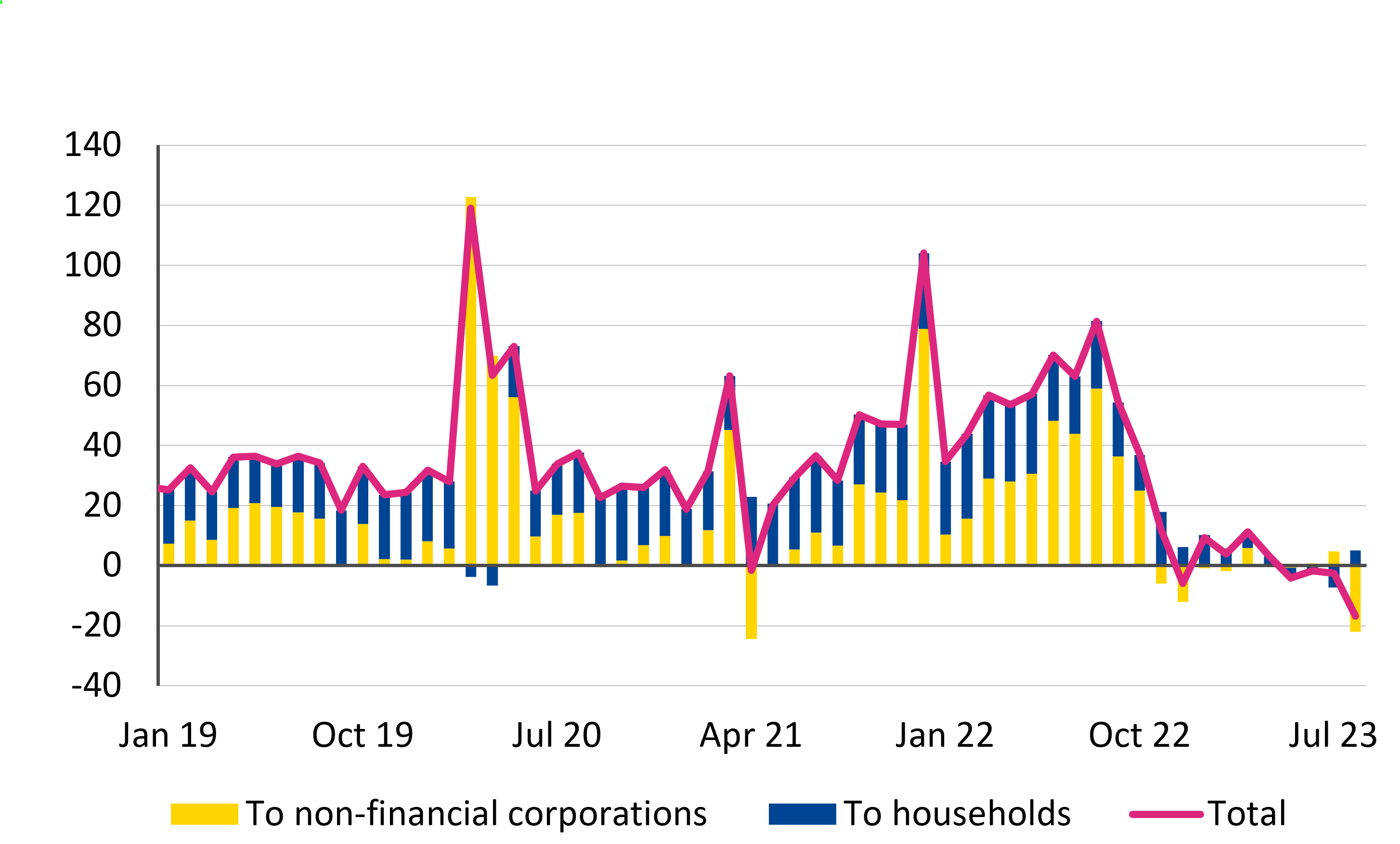

Weaker credit growth weighs on economic activity (see Figure 1). European institutions have lowered their latest growth projections, forecasting very little growth for 2023 and only modest acceleration in 2024. These adjusted forecasts reflect withering global demand – particularly for China – and stagnating consumption in the euro area. The labour market, which has been the backbone of economic resilience, though still performing strongly, has begun to show incipient signs of softening.

Figure 1: Loan provision to non-financial firms and households weaker

(flows in € billion)

Source: European Central Bank.

Though inflation seems to be slowly decelerating, the process will take time. Next year’s headline inflation is expected to be well above the European Central Bank (ECB) 2% target, and only reach that target by the end of the following year. The recent upward revisions of the inflation forecasts are largely driven by higher oil prices. In addition, much depends on the evolution of wages. Higher wage increases would support people’s income and help recover some losses incurred during the pandemic and the energy shock. But if wage growth remains high, the ECB may have to keep rates higher for longer to prevent second round effects.

Avoiding risks to financial stability associated with this outlook hinge upon private and public sector buffers to preserve stability in more adverse environments. The balance sheets of different sectors and financial institutions indicate both that the public support received during the pandemic and the energy crisis has left them with some buffers at an aggregate level, and that detecting vulnerabilities requires a more surgical look below the surface.

Buffers and sectoral vulnerabilities of households, firms, and banks

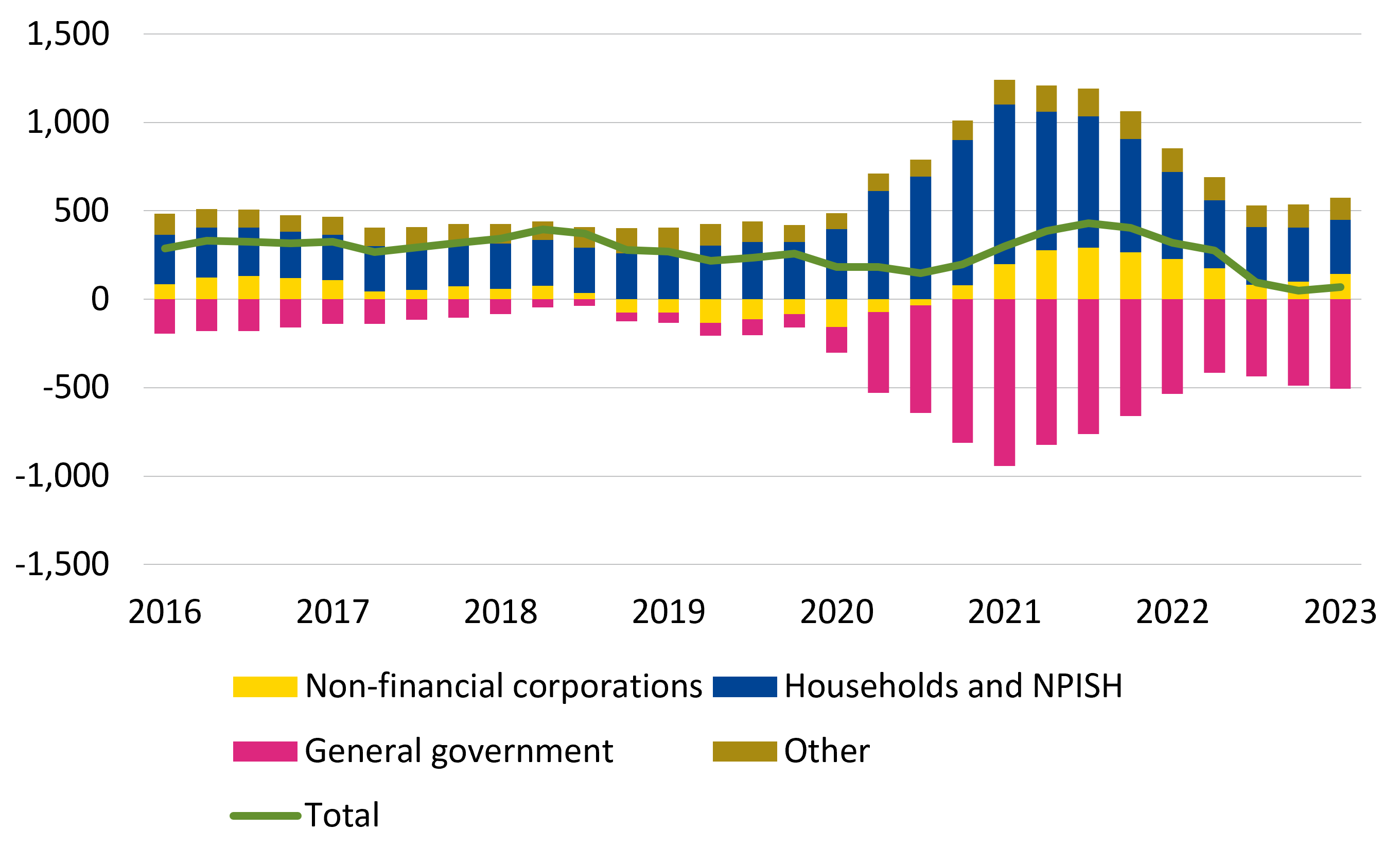

The financial situation of households improved over the past two years. During the Covid-19 pandemic, households’ precautionary savings spiked to a high of around 25% of their disposable income from a pre-pandemic average of 13%. The flow of savings later moderated as the saving ratio normalised, but the stock of accumulated excess remains on households’ balance sheets, providing a buffer against waning growth and rising interest rates (see Figure 2). Furthermore, nominal income increased with strong labour markets and inflation, leading to a drop in the debt-to-income ratio. Overall, households are less leveraged than before the pandemic. Still, those more exposed – such as lower income households and mortgage holders with variable interest rates – face higher credit risks. Less affluent households and the unemployed lost purchasing power during the pandemic, despite government support provided to the economy.

Figure 2: Firms and household could build up financial buffers during the pandemic thanks to support measures

(net lending in € billion, four-quarter sums)

Note: The chart shows net lending (+) and net borrowing (-) of non-financial corporations, households and non-profit institutions serving households, general government, and remaining sectors like financial corporations (other).

Sources: Quarterly Integrated Economic Accounts, Eurostat.

The corporate sector is also facing the credit tightening from a strong starting position. At the start of this year, the corporate interest burden was relatively modest at the euro area level and debt-to-income ratios had fallen below pre-pandemic levels. Debt servicing[1] is hovering around a manageable 5% of corporates’ gross value added. However, debt levels are high in several countries, interest payments are surging, and interest coverage ratios[2] are deteriorating. Slowing economic activity and higher interest rates will continue to weigh on corporates, and sectors with strong cost pressures may find themselves on weaker footing. Moreover, higher energy costs have weakened some sectors disproportionally and increases in wages will eat into profits. Small and medium-sized enterprises with less capital may feel these pressure points most.

The banking sector, however, appears able to weather the storm. The European Banking Authority (EBA) conducted a stress test including a worst-case scenario which showed that banks can overall manage the losses of such a scenario relatively well.[3] Rising interest rates have strengthened banks’ profitability and capital position. According to the EBA stress test, most institutions can manage a significant deterioration of their loans to households and firms, even if they come under more strain.

But not all banks are equally strong. Some banks, including some systemically important ones, show vulnerabilities in very adverse conditions. In addition, several banks have high exposure to commercial real estate – an area particularly affected by higher interest rates. We have discussed these risks in a previous blog on commercial real estate. Problems in real estate funds may even pressurise banks to take on more risk in that area. Financing costs will increase over time as more depositors look for more reward for their savings and revenues start to dry-up in step with diminishing credit generation. Market-based financing is also becoming more costly. Though the banking system looks robust now, individual institutions can face pressure, highlighting the need for an effective bank resolution framework to ensure the resilience of the financial sector.

Governments face a tighter fiscal space

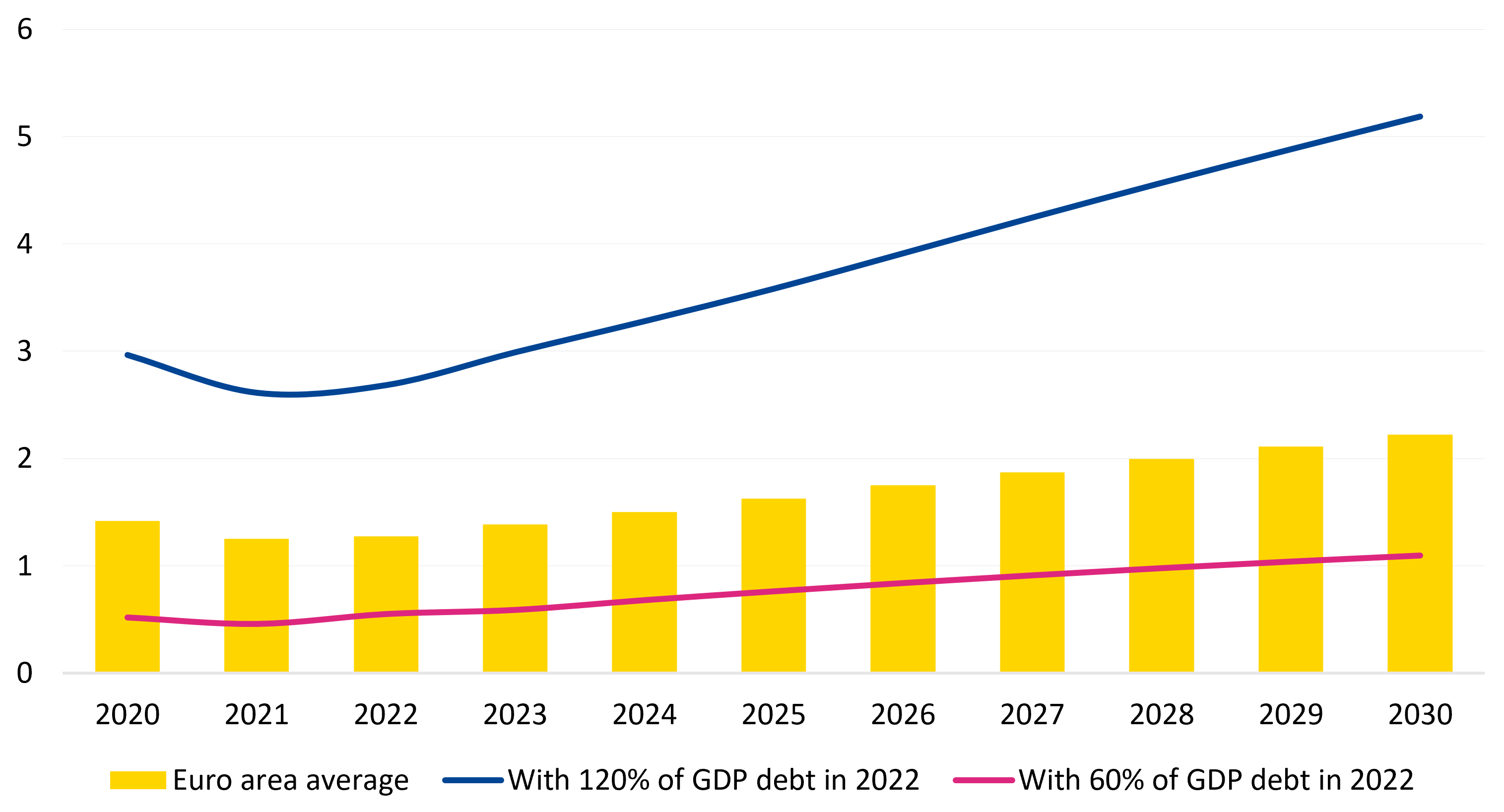

The robustness of private sector balance sheets came at the expense of the public sector (see Figure 2), which made great efforts during the pandemic and the energy crisis to buoy the economy. But these efforts amplified the vulnerabilities of governments. Due to higher interest rates, sovereign debt servicing costs are on the rise and fiscal space is shrinking. Market forwards indicate that euro area debt servicing costs will increase by around one percentage point of gross domestic product (GDP) over the next ten years on average, but the increase may be more than two percentage points of GDP for countries with high debt (see Figure 3). These numbers should be manageable if growth performs as per current expectations but may require some adjustments.

Figure 3: Governments’ interest burden to rise gradually, but persistently

(interest cost of existing marketable debt depending on starting position, as % of GDP)

Notes: The calculation is based on market forward rates as of 29 September 2023, assuming unchanged debt maturity composition. Maturing debt is rolled over at the forward rates of the average maturity of the portfolio. This mechanical exercise assumes that the primary fiscal balance (before interest payments) is zero, i.e. no additional deficit or debt repayment.

Source: ESM based on ECB and Bloomberg data.

The reduced fiscal space due to increased interest rates will be challenging for several countries, especially in the longer-term. Currently, not all countries have aligned their fiscal position with the requirements of the European Economic Governance Framework.

Moreover, the sustainability assessments and other international institutions indicate that some governments will require further fiscal adjustments to keep debt down when faced with our ageing societies. Any worsening of growth prospects in the near term would aggravate the debt sustainability outlook. Public money is also needed to fund climate change investments as well as digitalisation for increased productivity. The European recovery fund Next Generation EU, which focuses on climate and digital transition, will run out in 2026.

The Eurogroup and the European institutions agree that it is now time to consolidate budgets by phasing out energy support measures put in place since the outset of the Russian war against Ukraine. Keeping a prudent fiscal stance is essential when looking at financial markets. Sovereign spreads have been relatively contained over the past year with the help of the ECB’s bond purchases to compress spreads during the pandemic. It is conceivable that spreads might widen with the end of net purchases and quantitative tightening, although the ECB’s Transmission Protection Instrument will remain a mitigant.[4] This risk has, so far, been masked by better-than-expected growth and supportive global risk appetite over 2023. But as growth slows and monetary policy remains tighter for longer – either from interest rates or an acceleration of quantitative tightening – investors’ risk appetite can wane. This repricing would place additional strain on governments’ fiscal space.

Policy implications

The euro area is facing tighter credit conditions from a position of systemic strength. The private sector has buffers, and the euro area banking sector is looking robust. Risks have emerged for poorer and more indebted households and enterprise sectors more affected by the cost-push shock for production and financing.

Existing buffers would diminish faster – or could be depleted – if the euro area enters a more recessionary environment than foreseen in current forecasts. Vulnerabilities of individual financial institutions or sectors, such as commercial real estate, can be contagious. It remains crucial to strengthen crisis management capacity for banks.

The European Commission’s package on crisis management and deposit insurance makes some valuable propositions in this respect.[5] The full ratification of the revised ESM Treaty would also strengthen the financial infrastructure of banking union because it essentially doubles the resources available in case systemically important banks must be resolved.

Fiscal policy faces more systemic challenges, particularly with spending pressures emerging from long-term challenges. Higher interest burdens further reduce fiscal space at a time when ageing and investment needs for climate mitigation and adaptation are vital. Fiscal prudence is required now to avoid the brunt of volatile market sentiments as quantitative tightening progresses.

A timely agreement on the new Economic Governance Framework remains essential. The review should increase effectiveness of the framework through transparency, credible commitments that convince markets and people, strong governance, and enforcement.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Gergely Hudecz for his excellent support in preparing this column. I would also like to thank Giovanni Callegari, Angela Capolongo, Pilar Castrillo, Michael Kühl, Nicoletta Mascher and Vlad Skovorodov for their valuable comments and contributions.

Further reading

N. Mascher, J. Sole, R. Strauch (2023), “Fast and furious…but tameable”, ESM blog.

P. Fioretti, M. Skrutkowski, R. Strauch (2023), “ Commercial real estate and financial stability – this time, its different”, ESM blog.

Footnotes

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Author

Blog manager