Klaus Regling: Completing monetary union (op-ed in Global Public Investor 2017)

Completing monetary union

Necessary steps for a robust euro area

Klaus Regling, European Stability Mechanism

Global Public Investor 2017

Intra-European currency turmoil is no longer possible, cross-border trade in the euro area has benefited and transaction costs have fallen, but further action is needed to make the euro area more robust and ensure economic benefits of the single currency are fully realised.

In spite of Europe’s sustained economic recovery further action is needed to make the euro more robust and render the euro area more resilient.

The economic benefits of the euro are clear. Cross-border trade among euro area countries has benefited and transaction costs have fallen. Price transparency has improved, leading to greater competition and better and cheaper products. Even greater competition in the euro area would lead to higher productivity, benefiting prospects for economic growth.

The end of intra-European exchange rate volatility is another major benefit brought by the euro. Foreign exchange upheaval was frequent in Europe from the end of the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s until the start of economic and monetary union. Only by this joining of forces did Europe ensure that it did not lose relevance on the global stage. Today, it is a strong player next to countries such as the US, Japan, and China.

Stronger architecture for a better functioning monetary union

Monetary union has made significant progress over the past few years. Europe has come out of the euro crisis stronger than before, both economically and in terms of its institutional architecture. Budget deficits have decreased everywhere, and competitiveness has been regained through cuts in nominal wages and salaries. Policy coordination at the European level has been broadened and strengthened.

The European Stability Mechanism was established in 2012 and fills an important gap in the institutional framework of the EMU as a lender of last resort to sovereigns. This function did not exist before the crisis. The ESM has assisted five euro area countries, providing €265bn in loans. Money is disbursed under the strict condition that countries implement comprehensive economic reforms.

This financial solidarity comes at no cost to the taxpayer, though ESM shareholders do take on the risk associated with the programmes. Another innovation is the plan for banking union, which saw the establishment of the Single Supervisory Mechanism and the Single Resolution Mechanism.

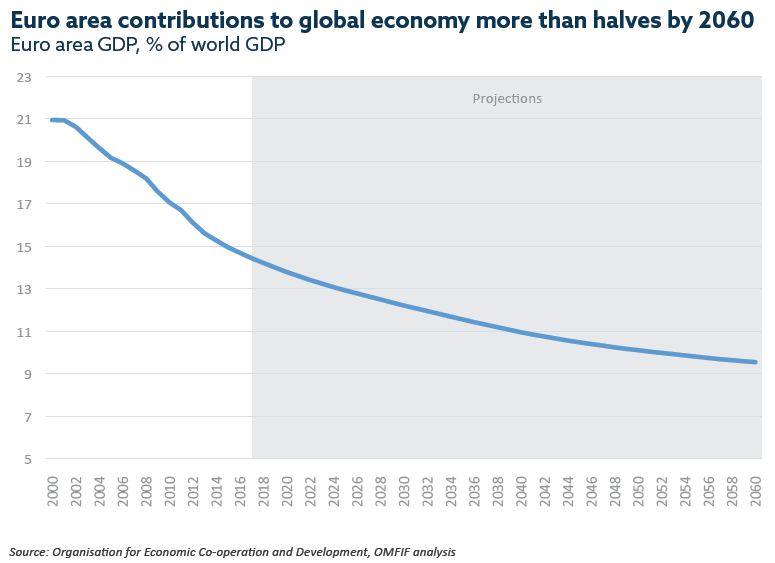

Europe deployed an effective strategy to move out of the financial crisis but that doesn’t mean enough has been done to boost the strength of the euro area. While the euro area made up 21% of the world economy in 1999, that share now stands at 15%. By 2060, it is projected to be just 10%. The weight of individual European countries, even the large ones, would be much less.

To start with, member states should apply the surveillance rules, established under the various mechanisms, to themselves. Second, countries must continue to implement structural reforms to raise potential growth and should implement country-specific recommendations more consistently. These two points are true for all euro area nations, not just for current or former ESM programme countries.

Steps for strengthening the EMU

Any new steps needed to complete the EMU are modest compared to the progress already made. Monetary union does not require a full fiscal union to function properly, nor a full political union. But certain additional measures would be useful.

First, a complete banking union would improve financial integration and risk-sharing via markets. An important step for completing this union would be some form of European deposit insurance. Before this can happen legacy problems in banks need to be addressed: no country with a healthy banking system should have to pay for past mistakes made by the banks of neighbouring economies. Consequently, it will be some time before such insurance exists.

Different models are under discussion, and the advantages would be considerable. In particular, the risk of a nationwide bank run disappears. When an EMU member state is under attack from markets, people would be reassured that it is not just their own government backing their money, but the entire euro area. The impetus for a bank run would vanish.

Capital market union would also strengthen financial integration and make the euro area more robust. By harmonising corporate, tax and insolvency laws, European countries would lower barriers for equity flows and other investments across borders. This would facilitate equity investments from one country into another and help reduce Europe’s excessive reliance on bank funding.

Another step towards making the EMU more robust would be a limited fiscal capacity to address asymmetric shocks. There is the fear in some member states that this could lead to debt mutualisation and permanent budget transfers. But examples in the US show this need not be the case. US states can, for instance, draw on a reserve fund or supplementary unemployment schemes to help them through difficult times, and then refund the money later.

Enhanced role for the ESM

The final issue is a ‘European Monetary Fund’, which is under discussion. The International Monetary Fund has played an integral part in efforts to resolve the continuing Greek debt crisis. But there seems to be a growing consensus in Europe that the IMF will not play the same role in any future euro area crisis. The ESM could then play a bigger role.

The ESM no longer just finances assistance programmes. It participates in missions to the countries it is assisting, analyses debt sustainability and monitors countries’ repayment capacity through an early warning system. However, it is conceivable that the ESM might develop into an institution that is even more similar to the IMF than it is now. This would require at least a change in the ESM treaty – if not an amendment of the associated European Union treaty – and would therefore require a consensus among member states.

The euro area did well to defend the single currency, which brings many economic benefits, during the crisis. We need appropriate steps to complete monetary union – but required action is relatively modest. The broad support the euro enjoys among voters gives policy-makers the mandate to take these necessary steps towards stronger monetary, banking and capital markets union.

Klaus Regling is Managing Director of the European Stability Mechanism and Chief Executive of the European Financial Stability Facility.

Author

Contacts