Resilience of countries that benefited from financial assistance

Resilience of countries that benefited from financial assistance

Spillovers, or contagion, raised the cost of the crisis for the euro area.

A key challenge in the euro area debt crisis was contagion: stress in one member state affecting financial markets in another. Tensions spread as investors demanded a higher risk premium to hold the government bonds of even those Member States not directly affected by the initial shock. In other words, contagion increased the costs of the crisis for the euro area.

During the crisis, in extreme cases, investors priced in some risk of a country exiting the euro area.

Given the characteristics of spillovers in a currency union, contagion may also have been driven by markets’ perception of redenomination risk: the risk that a financial asset is converted from one currency into another of lesser value. In the euro area, this could be understood as investors’ perception of the risk that a member state introduces a parallel currency or, in an extreme case, leaves the currency area. This can have implications for other Member States and raise the risk of contagion, but appropriate policies can mitigate this risk.

Since the crisis, however, these fears, and contagion, have receded.

Former programme countries have become less affected by such external shocks, demonstrating the results of the reforms carried out during the programmes. Despite volatility in European sovereign debt markets in 2018, the spillovers to former programme countries were relatively limited compared to previous episodes of market stress. Contagion, and investors’ perceptions of redenomination risk, have been contained.

Contagion risk

We compare 2016–2018 to the start of the crisis period, 2009–2011.

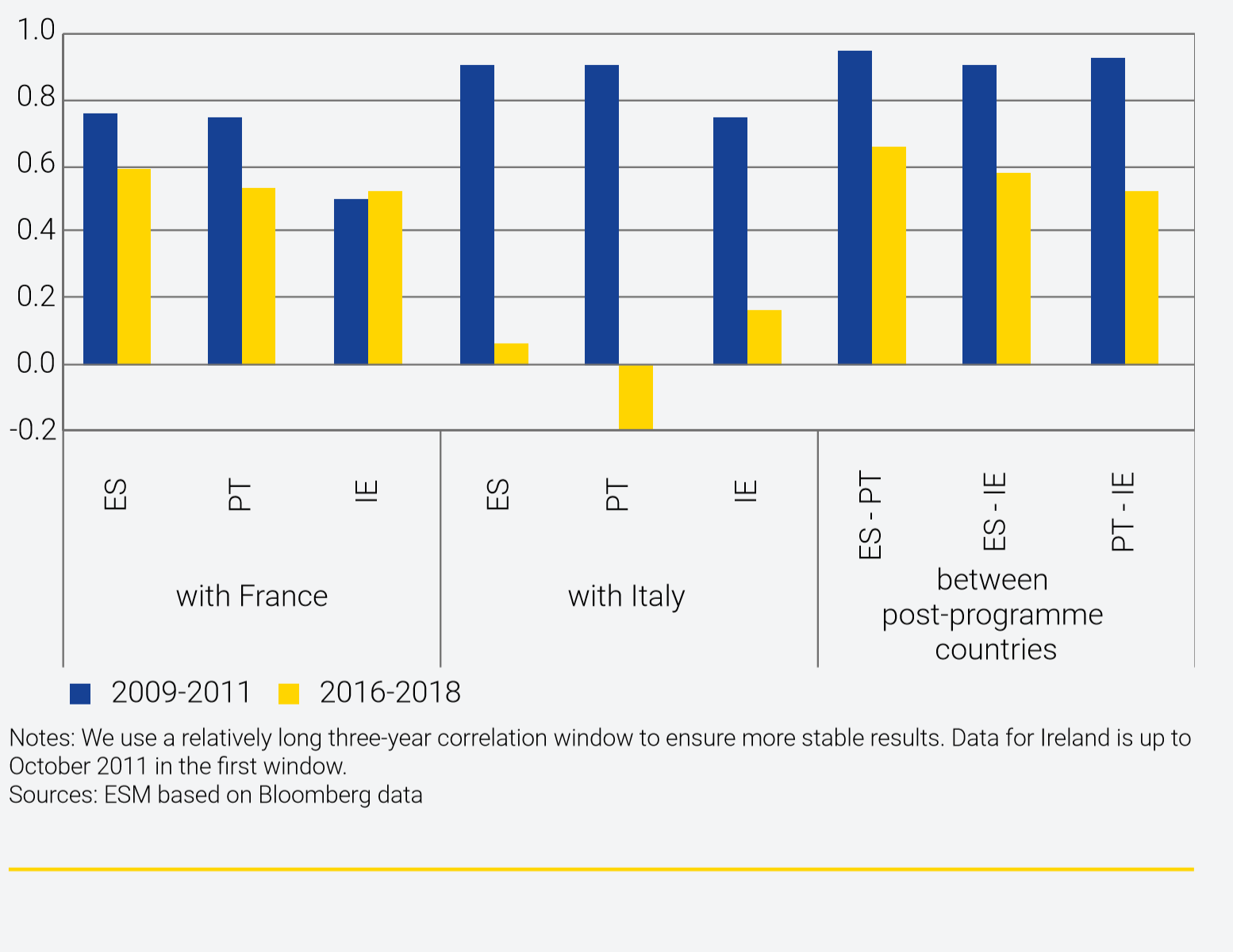

One way to look at the extent of contagion is to assess the correlation of asset prices. Methodologies range from simple correlations to more complex econometric techniques.[1] Here, we present the simple correlations across sovereign credit spreads of selected countries, and two measures of redenomination risk. Due to data limitations, we focus on three Member States that benefited from financial assistance (Ireland, Spain, and Portugal) and relate them to two major euro area economies that experienced some market volatility over the past two years (France in 2017 and Italy in 2018). We compare two three-year windows: the crisis period (2009–2011) and recent years (2016–2018).[2]

Over the long-term, post-programme countries’ bond spread developments appear to have aligned more with the country having steadier spreads.

Based on this simple exercise, it appears that the sovereign credit spreads of the three post-programme countries have become less vulnerable to external developments. Figure 20 depicts the one-on-one (pairwise) correlation of sovereign credit spreads of each of the three post-programme countries to France and Italy, respectively, as well as between each pair of the three post-programme countries. It shows that the three countries’ spread levels, which reflect country-specific risk premia, demonstrated higher correlation with Italy than with France during the crisis period, but that the correlation with Italy weakened in the recent three-year window.[3] In other words, the spreads of the three countries were more highly correlated with France than with Italy in the recent period. This development can be interpreted as a sign of improved resilience of the three post-programme countries to external developments (Figure 21).

Figure 20: Correlation of 10-year sovereign credit spreads

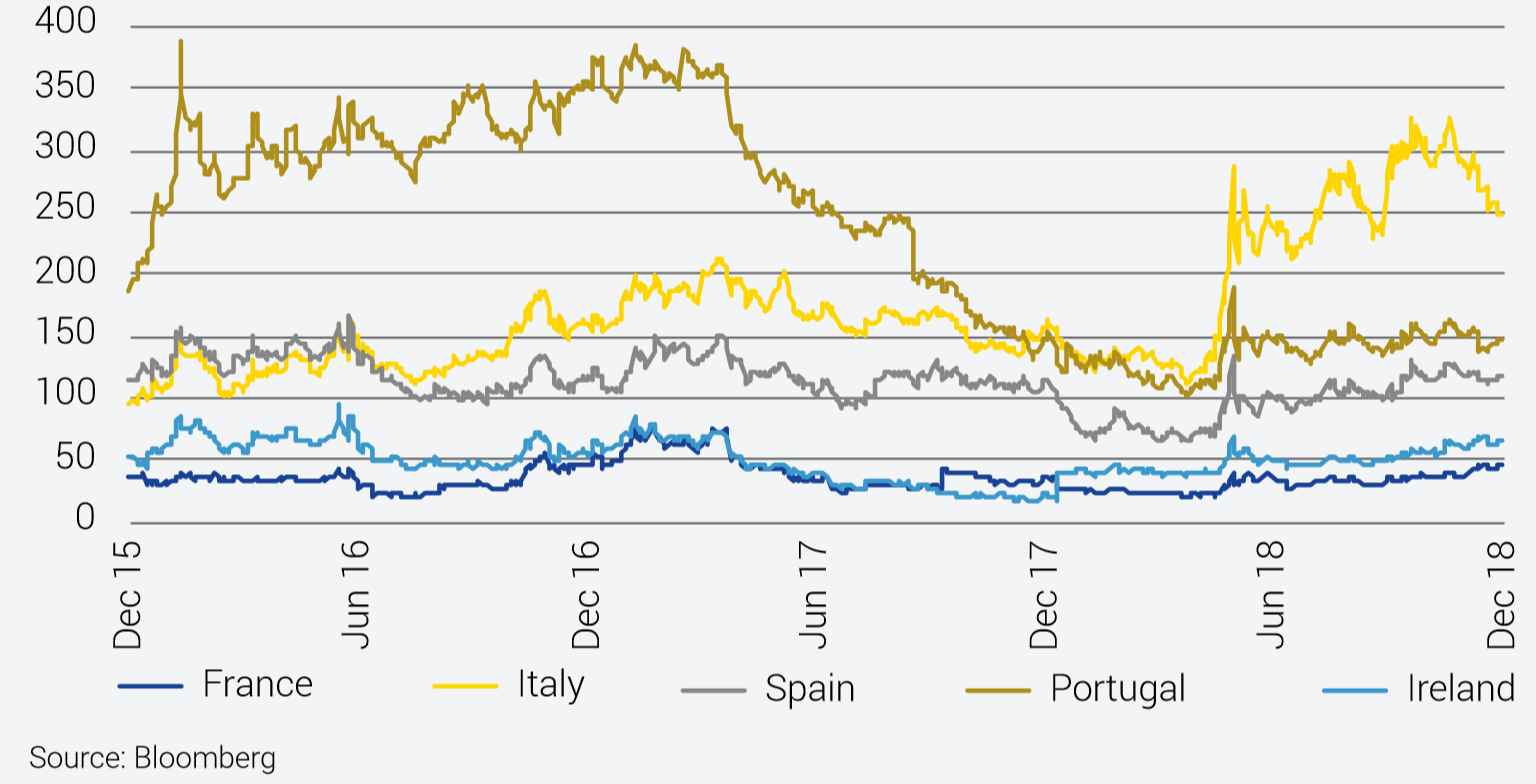

Figure 21: 10-year sovereign credit spreads vs Germany

(in basis points)

(in basis points)

Investors also appear to focus more on country-specific factors.

Correlations between each pair of the three post-programme countries also declined somewhat compared to the crisis period. This may signal that investors have a greater focus on country-specific factors and differentiate more between these countries. The short-term liquidity and volatility of these markets may still be correlated, but it appears that longer-term trends have become more idiosyncratic. This is a welcome development, which can also help to reduce the risk of contagion.

Redenomination risk

Financial instruments can provide insight into investor perceptions of the risk a country might leave the euro area.

The market perceptions of redenomination risk can be derived from financial instruments. De Santis (forthcoming)[4] proposed a redenomination risk measure based on the difference between credit default swaps (CDS) issued in US dollars and those in euros, the quanto-CDS. This difference reflects the insurance against the risk of euro devaluation or the introduction of an alternative currency. Under normal circumstances this is close to zero, but it can increase in times of market stress. Market perceptions of country-specific redenomination risk can be computed by taking the country’s quanto-CDS spread relative to the German quanto-CDS, as the sovereign bonds of Germany are rated AAA by credit rating agencies and hence likely considered relatively safe by investors.[5] Yet we note that the use of CDS as an instrument to derive redenomination risk has to be handled with care, given the limited liquidity and transparency of the market.[6]

Perceptions of such risk declined substantially after 2012.

Figure 22 depicts the quanto-CDS spreads for the five countries in our sample since 2009. It shows that the perception of redenomination risk by markets increased more broadly during the euro area debt crisis, but that spillovers have dampened in recent years. Consistent with these observations, a recent academic paper covering a broader sample also finds that redenomination-risk spillovers are muted for most euro area member countries, and the number of those exposed to such risks declined after 2012.[7]

Post-programme countries have been less affected by such shocks recently.

Another measure of redenomination risk also corroborates these findings. Gros (2018)[8] suggested that market perceptions of redenomination risk could also be measured by comparing the spread between different CDS vintages: CDS contracts issued under the 2003 International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) convention did not explicitly refer to redenomination as a credit event, but CDS contracts based on the new 2014 documentation provide stronger protection against such risk. Hence the difference between the two types of contract may point to investors’ concerns about redenomination risk.[9]

Figure 22: Quanto-CDS spread, 20-day moving average

(in basis points)

(in basis points)

Other metrics and research results also support this conclusion.

As shown in Figure 23, redenomination risk has been repriced around political events. Although data for this measure have become available only in the last few years, they nonetheless cover events such as the French elections in 2017, and the government formation in Italy last year. In line with the pattern shown by simple correlations and the quanto-CDS metric, it appears that the three post-programme countries have been less affected by external shocks recently.

Figure 23: Spread between different CDS vintages, 20-day moving average

(in basis points)

(in basis points)

Drivers of resilience

Spillovers across markets have declined since the crisis…

Overall, spillovers across markets have been reduced since the crisis period, due to European policy initiatives and Member States’ own efforts.

…because euro area fundamentals are more robust than before the crisis…

First, there are sound macroeconomic reasons for the more limited spillovers: euro area fundamentals are now more robust than before and during the debt crisis years, particularly in former programme countries. Domestic efforts supported by adjustment programmes reinforced Member States’ ability to weather external shocks.

…while low interest rates and ECB programmes may have softened the impact of external shocks.

Second, the strengthening of the euro area stability framework has been instrumental in reducing contagion risk. Markets considered the creation of the ESM and the introduction of the ECB’s outright monetary transactions instrument, for example, as key innovations to defuse tensions in sovereign debt markets.[10] Other institutional reforms, such as enhanced banking supervision and fiscal rules, also play a vital role in ensuring the euro area’s stability.

Third, historically low interest rates and the presence of the central bank in government bond markets through the ECB’s public sector purchase programme (PSPP) may also have dampened the impact of external shocks.

Work towards stronger fundamentals and an even more robust EMU framework should continue to cement these achievements.

The combination of these factors helped to contain the market impact of policy uncertainties in some Member States, and ensured that these remain idiosyncratic rather than systemic. Furthermore, with contagion risk reduced, investors also seem to have a greater focus on country-specific factors and differentiate accordingly. Nevertheless, contagion has decreased but not disappeared, and hence there is no room for complacency: it is imperative to continue the work towards stronger macroeconomic fundamentals and a more robust institutional framework by deepening EMU.

[1] See, for example, Martin Hillebrand et al., European Government Bond Dynamics and Stability Policies, ESM Working Paper 8, 2015. For recent overviews of other measures of contagion by market analysts see for example Clemente De Lucia et al., Contagion: Italy and the role of fiscal similarity, Deutsche Bank, 12 November 2018; and Matteo Crimella, Moderate Spillover from Italian Turmoil, Goldman Sachs, 1 June 2018.

[2] We use 10-year government bond yields compared to Germany as a benchmark, in line with common practice. We exclude 2012 from the crisis period sample, due to structural breaks such as the Greek private sector involvement and the announcement of the ECB’s outright monetary transactions instrument.

[3] The correlation of sovereign credit spreads between Italy and Portugal over the entire 2016–2018 sample turned marginally negative due to Portugal’s return to investment grade rating in 2017.

[4] Roberto A. De Santis, Redenomination risk, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, forthcoming.

[5] Germany is the common benchmark for the euro area sovereign debt market, and the use of countries’ quanto-CDS relative to Germany rests on the idea that such a spread would be close to zero if the market perceives the risk of a euro area break-up as negligible. For further details, see pp. 8 and 15 in Roberto A. De Santis, a measure of redenomination risk, ECB Working Paper 1785, April 2015.

[6] With respect to quanto adjustment, one has to be also aware that the majority of traded CDS contracts are USD-denominated and the EUR denominated contracts are less liquid.

[7] Nicola Borri, Redenomination-risk spillover in the eurozone, Economics Letters 174 (2019), pp. 173–178.

[8] Daniel Gros, Italian risk spreads: Fiscal versus redenomination risk, VoxEU.org, 29 August 2018.

[9] The spread between the ISDA 2003 and 2014 CDS definitions are wider than the quanto-CDS spread, because it captures not only redenomination risk, but also provides stronger protection to sovereign bond holders more broadly. Since the CDS 2003 definitions are perceived to be less effective in hedging some risks, such as the redenomination risk, potential buying pressure is concentrated on the 2014 contracts, partly explaining the asymmetry in the relative price movements. Hence caution is warranted when translating these numbers into proportions as to what extent redenomination risk specifically can explain the widening of sovereign credit spreads.

[10] See, for example, George Cole and Matteo Crimella, EMU Bonds Resilient to Italy Risks… But Watch Growth, Goldman Sachs, 24 October 2018.