The butterfly effect of geopolitical conflicts

The butterfly effect of geopolitical conflicts

0:00 minIn today's interconnected world, what happens on the other side of the globe – even the seizure of a single commercial ship – can directly impede euro area economies. This is an illustration of the butterfly effect, when geopolitical tensions, though seemingly distant, can hit close to home. As conflicts simmer in key regions of the world, vital trade routes, like the Red Sea, the Strait of Hormuz, and the South China Sea are increasingly coming under threat. These routes are not just lines on a map; they are the arteries through which goods and energy flow.

In this blog post, we try to quantify the potential impact of disruptions in maritime trade on the euro area, focusing on input goods from Asia and on energy from the Persian Gulf. Any disruption in these routes can lead to delays, shortages, and higher prices, thus negatively affecting euro area output and potentially financial stability. The diversification of suppliers and the security of shipping routes are key to reducing the impact of geopolitical risks.

Shipping the main trade channel for Europe

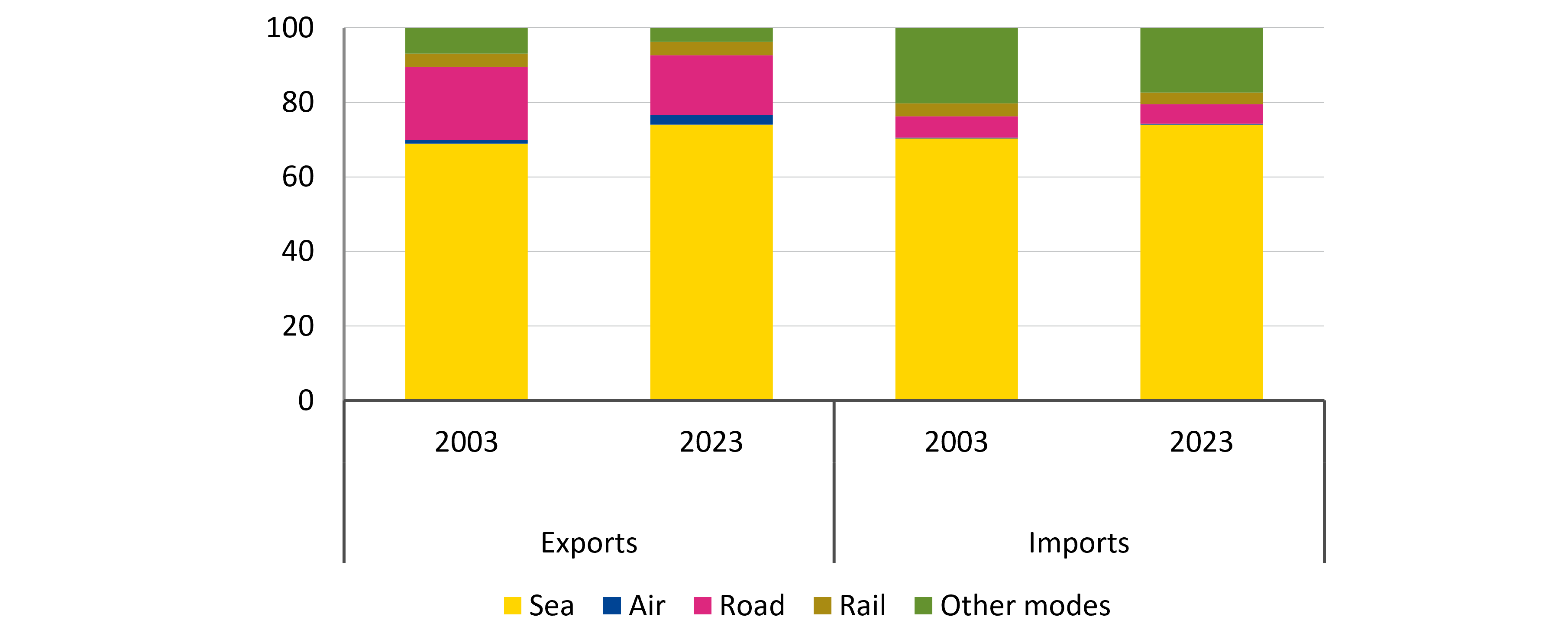

European trade in goods heavily relies on shipping, making up over 70% of both imports and exports in 2023 (see Figure 1). Key maritime routes have become vulnerable to geopolitical conflicts. For example, recent attacks on vessels transiting the Red Sea have reignited risks of supply-chain disruptions and sprouted a significant fear: how would this affect Europe if these disruptions last longer or involve other regions?

Figure 1: Trade in goods between Europe and the rest of the world are mainly transported by sea

(volume as % of total, based on tonnes)

Notes: The figure shows the quantity of extra-European Union trade in goods by mode of transport in 2003 and 2023. Other modes include post, fixed mechanisms, inland waterways, self-propulsion, and others.

Source: Eurostat

What if goods supply from Asia via ships is delayed or even suspended?

Because of the attacks by Houthi rebels on cargo vessels, shipping transit via the Red Sea – a systemically important shipping route [1] that carries about 40% of European-Asian trade – has plummeted by 60%. This was mostly offset by rerouting traffic through the Cape of Good Hope and transporting some goods by plane or over land.

Various elements make rerouting challenging. Alternative transport methods are more expensive and at times more time consuming, thus driving up overall costs. Unlike the impact from the Covid-19 pandemic, recent events in the Red Sea have not triggered supply bottlenecks and have had limited impact on economies. [2]

Still, if rerouting persists, logistical issues could arise when the demand for carrier ships exceeds the available supply at a given moment. [3] Additionally, existing port congestions in the area [4] could further hamper trade. Bad weather, something the Cape of Good Hope is well known for, could also increase fuel consumption and thus the number of stops along vessels’ journeys, [5] an additional constraint on port capacities. These issues ultimately make global supply chains more vulnerable.

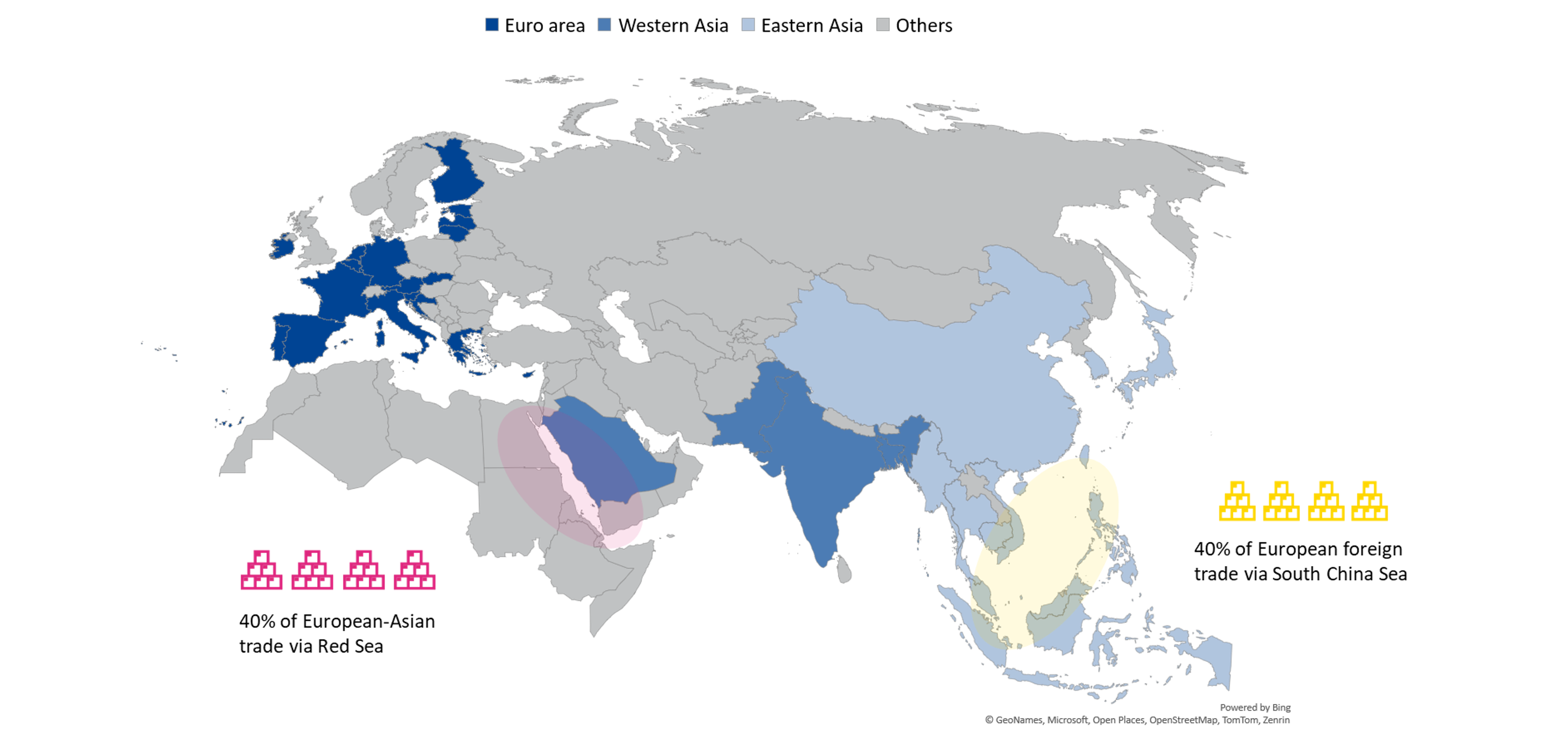

Moreover, before reaching Europe, some ships departing from Asia cross another chokepoint: the South China Sea (see Figure 2). [6] Disruptions in the South China Sea, arising from geopolitical conflicts in the region, could also be substantial for the euro area. Impaired global trade from (East-) Asia could severely damage the euro area through disruptions to supply chains, given its substantial dependencies on this continent for essential inputs of production, something that became all too apparent during the pandemic.

Figure 2: Two chokepoints for trade from Asia

Notes: The map highlights the countries used in the analysis. Eastern Asia comprises China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Indonesia, Cambodia, Myanmar, Vietnam, Philippines, Thailand, and Malaysia. West Asia includes India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Saudi Arabia. Countries were selected based on data availability.

Sources: ESM elaboration on Eurostat and European Commission

In a scenario where rerouting around the Cape of Good Hope lingers on – due to persistent or escalating geopolitical conflicts in the Red Sea – shipping capacity would need to increase roughly by 30%, according to our calculations. [7] Should it be impossible to increase capacity on short notice, given no alternative transportation options, supply chain problems would emerge. Without the possibility to receive those missing goods [8] from other regions, production in the euro area could fall by about 1.5%. [9] The impact would be heterogeneous across euro area countries, depending on the trade exposure of countries to the Asian region. Germany and smaller countries would be mostly affected by a drop of inputs from Asia, while France, Italy, and Spain would be less affected. However, this is not the only channel through which geopolitical tensions can impact the global economy.

An escalation of the conflict in Middle East could disrupt energy supply

An escalation of conflict in the Middle East could threaten global and European energy supplies. The Strait of Hormuz is a crucial chokepoint for the global energy transit, with 30% of the world’s oil passing through it daily and 20% of global liquefied natural gas trade. Therefore, bottlenecks in that route could substantially impact oil and gas prices, and potentially the euro area’s energy supply given European countries’ increasing energy dependency on the region. Recently, larger euro area countries have signed multiple long-term contracts with Qatar for the delivery of 10 metric tonnes of liquified natural gas per year starting from 2026. [10] Although the euro area improved resilience by phasing out Russian gas, it risks increasing dependency on other countries and longer shipping routes.

Targeted attacks on ships carrying oil and liquefied natural gas would have an immediate impact on oil and gas prices. Increased instability in the region and paramilitary aggression cannot be excluded. That risk could persist in the future when Europe will import more liquefied natural gas from the region. According to our calculations, a blockade of one ship carrying liquefied natural gas to Europe would be equivalent to more than 1% of monthly Russian gas delivery before the Russian war started. A reduction in gas consumption due to the energy transition and diversifying suppliers from other regions might mitigate that risk.

Diversify suppliers and secure shipping routes to mitigate geopolitical risks

Maritime trade is crucial for global business, but it is also an economic weak point that can be easily disrupted. Impaired supply chains due to geopolitical risks can have implications for economic growth and for financial stability. Europe is working on making its supply chains more resilient by diversifying them and finding new energy sources. However, there are still significant vulnerabilities that require close monitoring to detect and mitigate risks to economic activity and financial stability as early as possible.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Pilar Castrillo and Rolf Strauch for the valuable discussions and contributions to this blog post, and Raquel Calero for the editorial review.

Footnotes

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Blog manager

Authors