Financial stability risks in Europe - speech by Rolf Strauch

Rolf Strauch, ESM Chief Economist

“Financial stability risks in Europe”

JP Morgan Investor Seminar

Washington DC, 12 April 2019

(Please check against delivery)

Good morning,

It is a pleasure for me to speak here on the second day of the JP Morgan Investor Seminar. Following the remarks by Tobias Adrian on global financial stability, I would like to focus on the main risks to financial stability from a European perspective. I will first reflect on the European outlook in the global context, then outline five financial stability risks, and finally sketch the current policy agenda to make the euro area more robust.

The starting point is that euro area growth is moving towards normalisation. All forecasts of major institutions point to a slowing of growth compared to the past years. Current projections indicate growth rates of 1 to 1.6% for 2019 and 2020, which is centring around potential-growth estimates. This is a reflection of a maturing economic cycle, certainly outside Europe but also for the European economy itself.

The main reason for softer growth for the euro area has been the external environment. Domestic demand is supporting growth, despite a temporary dip in production. Recent performance was weaker due to special factors affecting, among others, the car industry. Otherwise domestic fundamentals appear fairly strong. Therefore, most projections foresee some growth recovery next year. Labour markets are tight in major economies, showing signs of labour scarcity. Wage growth has resumed, increasing to above 2% for the euro area and employment growth continues. With more disposable income, domestic demand is expected to be growth-supportive.

The strong growth performance in recent years was not based on large current account deficits, as it was during the years leading up to the past crisis. The euro now has a current account surplus, with most countries maintaining a balance, while Germany and the Netherlands have very big surpluses vis-a-vis the rest of the world. At the same time, there are no signs of significant overheating, which were visible prior to the crisis a decade ago.

Against that background, what are the risks that could derail a normal cyclical slowdown of growth? And what could consequently cause financial instability?

Let me outline five financial stability risks and put them into context.

First, the most immediate risk for Europe is certainly Brexit, though short-term repercussions are less acute now due to the extended deadline. In the short term, in any case, financial stability risks related to financial contracts and liquidity needs of financial institutions are well contained. This stems from the precautionary steps taken by supervisory authorities as well as the ECB and the Bank of England. Now also a somewhat higher degree of preparedness may be achieved for the real economy, where risks emerge in the short run and beyond.

Brexit is a lose-lose situation for the UK and the other European countries, where losses are overall clearly tilted towards the UK. For some time now, negative effects have been already apparent for the UK business climate and investment, and for household incomes and wealth - which have suffered substantially in terms of purchasing power compared to other countries.

Depending on how the exit plays out, these effects are expected to become more pronounced. Output in euro area economies having close ties with the UK remains of course exposed to the transition structure and final arrangement.

Second, on the external side, there may be risks of a sharper-than-expected growth slowdown outside Europe, which could also affect the euro area outlook. Risks here seem to be tilted to the downside, while there remains also some upside. Most forecasts have now internalised the cost of past trade measures imposed by the US and other countries. Any reversal of these measures presents therefore an upside. Similarly, the first effects of a more expansionary policy stance in China are becoming apparent.

On the downside, complications in trade negotiations are one of them. We all know, of course, that trade wars have no winners. To the contrary, an escalation of tariffs and other barriers could seriously damage growth prospects in Europe and elsewhere. And we have seen that even just the threat of new tariffs damages confidence and investment. This could be particularly damaging during a cyclical slowdown as we are experiencing right now.

A third risk are the unintended consequences of monetary policy. There seems to be broad-based consensus that the major central banks – particularly the Fed and the ECB – have managed the transition towards normalisation smoothly and with a great deal of forward guidance.

Looking ahead, there is some uncertainty regarding the future monetary policy course. On the one hand, tighter monetary policy path than currently expected by markets, in view of more lenient recent central bank action and guidance, could lead to repricing. On the other hand, a continued path of very low interest rates may lead to a more risk-seeking behaviour among investors, therefore to a higher build-up of leverage in the public and private sectors, and negative consequences for banks.

How do we see the exposure of the public and private sectors in the euro area in this context? On the public sector side, high debt levels not only imply a constraint on fiscal space but also a financial vulnerability. In the euro area, some countries still face high debt levels and refinancing needs, which especially in a low growth environment raise questions about longer-term sustainability.

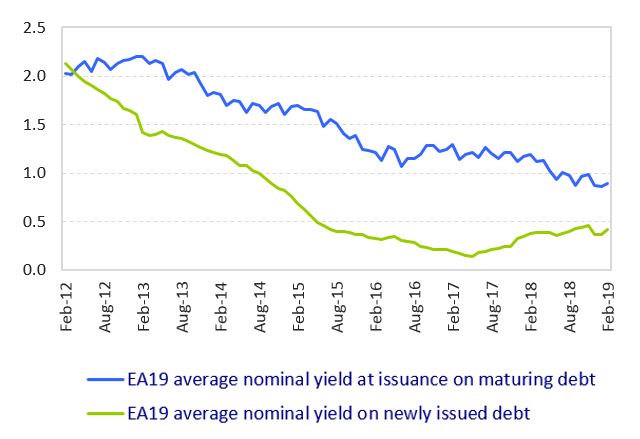

In recent years, the experiences of Portugal in 2016 and Italy in 2018 show how market anxieties about policy actions in cases with high debt levels can have a strong impact on financing costs. Having said this, there are clear mitigating factors. First, the prevailing refinancing rates are still substantively below those at which currently maturing debt was issued [Chart 1.].

Chart 1. Average nominal yields on maturing and newly issued debt (per annum, %)

Note: Average nominal yields of issuance refer to the yields treasuries promise to pay for newly issued government debt (including bills and bonds); Average nominal yields of redemptions refer to the yields treasuries promised to pay for those maturing debt securities when issued (including bills and bonds);

Source: ECB.

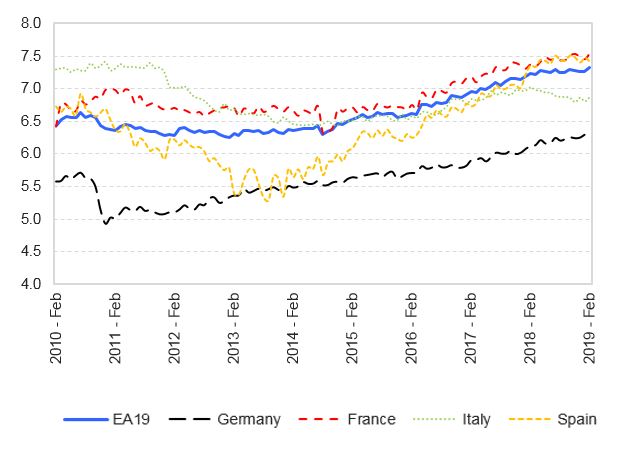

Second, most countries have used the period of low interest rates to extend the maturity profile of their debt significantly [Chart 2.]. That means they have markedly lowered roll-over risk, and created space to diversify their issuance across the yield curve. This mitigates interest rate volatility in sovereign funding. These factors should give reassurance to investors.

Chart 2. Weighted average residual maturity of government debt

Source: ECB.

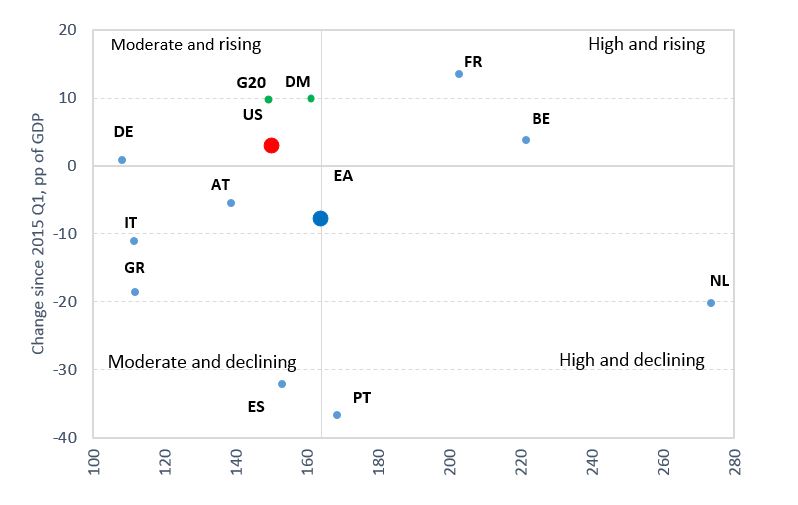

On the private sector side, credit to the private non-financial sector in the euro area is relatively high compared to the US, but this does not point to a generalised risk. The non-financial private sector’s indebtedness is relatively moderate in Germany, and decreasing steadily in Spain and Italy, while it remains elevated and rising in France. [Chart 3.]

Chart 3. Credit to private non-financial sector (% of GDP)

Source: BIS.

As for household debt in particular, it is low in Germany and Italy. It is the highest among countries which are economically relatively strong and advanced in the capital market participation of individuals, like the Netherlands and Luxembourg. And here high indebtedness is also matched with high values of financial assets.

Fourth, the euro area banking sector has become much safer compared to a decade ago, but some vulnerabilities remain. Throughout the euro area, capital buffers, liquidity and governance have been strengthened significantly, supported by a much stronger regulatory and supervisory architecture. This conclusion is supported by numerous metrics. But there remain some areas of concern.

While profitability has improved and was highest last year since the crisis, a number of banks in Europe have not achieved sufficient profitability to be attractive to investors or have the inherent strength to build up capital. Indeed, on average banks still do not earn the cost of equity, which is requested in markets.

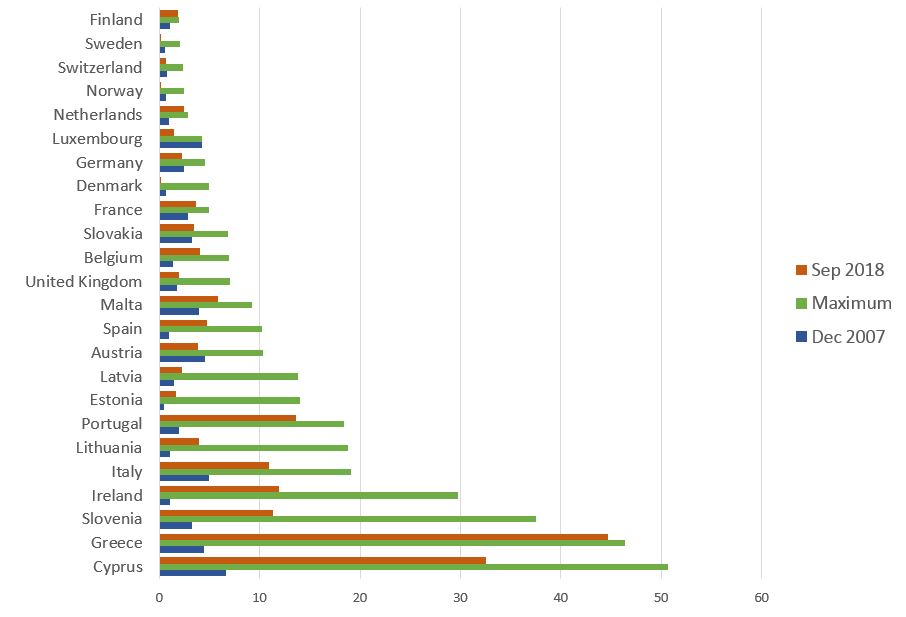

Another risk factor for euro area banks are non-performing loans (NPLs). Despite good progress in the reduction of the stock of NPLs – thanks to the sustained efforts of banks, national and European authorities – the level of bad loans in some euro area countries remains elevated. [Chart 4.] Banks need to keep up the pace of reduction, as NPLs tie up capital, put pressure on profitability, increase funding costs and reduce banks’ appetite for new lending.

Chart 4. Gross NPL ratios for European countries

Source: SNL Financial, ESM calculations.

I welcome the fact that the European Commission has developed an Action Plan to accelerate the reduction of NPLs. The Third Progress Report of the European Commission shows that the declining trend in NPL ratios continues. NPL ratios stood at 3.8%, on average, for the euro area in 2018, but that represents a very high total NPL volume of nearly €580 billion.

Banks in a number of euro area countries also remain vulnerable due to their significant exposure to sovereign bonds of their domestic government. Banks have a strong bias towards taking up liabilities of their home country, which reinforces the sovereign-bank nexus. The share of domestic government debt securities in total bank assets is significantly higher in several euro area countries compared to the US, and it is in some cases markedly higher today than before the financial crisis.

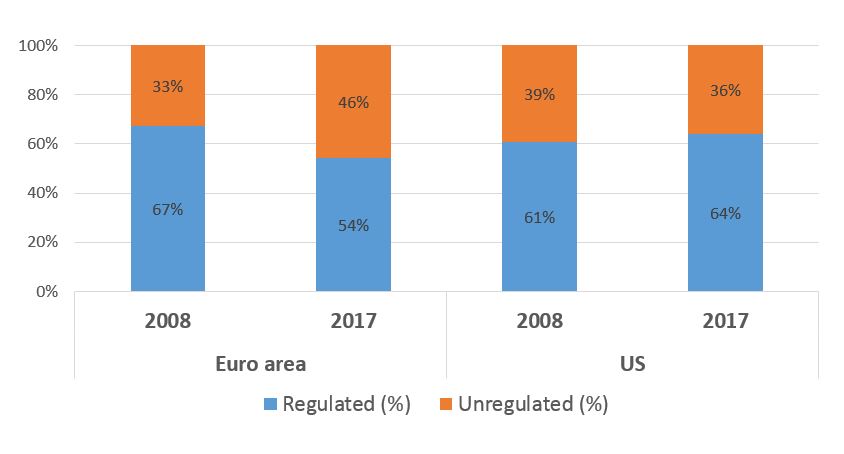

Fifth, we need to look closely at financial activities conducted by unregulated institutions – the so-called shadow banking sector — which can create some vulnerabilities for the broader financial system. In the euro area, shadow banking is increasing in proportion to the regulated financial sector, and nearly half of financial assets are intermediated by the less regulated shadow banking industry. In the US, the contribution of shadow banking to the financial sector has fallen slightly since 2008 and amounted to 36 percent in 2017. [Chart 5.]

Chart 5. Structure of the Financial Sector

Source: IMF, WEO.

The increasing share of shadow banking in the euro area is the result of several factors. Policies promoting capital markets, higher costs of regulation for the banking sector, and a shrinking of bank balance sheets play a role. Shadow banking has clear benefits as it diversifies the sources of financing for the economy.

However, risks can arise in this generally much less regulated sector, for instance from liquidity and maturity transformation. This may cause spillovers to the wider financial system during times of stress. European banks remain highly interconnected with the shadow banking system by providing funding to entities engaged in shadow banking activities.

More specifically, investment funds have in recent years rebalanced their portfolios towards lower-rated debt securities, seeking higher returns in the current low-interest rate environment. This, combined with the increasing duration of exposures, declining liquidity buffers, and strategies that exploit short-volatility and long-carry trades, make funds exposed to greater credit and market risk.

Policy response - we are better prepared for a future crisis

As a response to the global financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis, Europe has taken major steps to improve the institutional setup of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). Two quantum leaps stand out: the creation of a banking union, and the establishment of a crisis resolution mechanism. The banking union is supported by the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM), and we at the ESM have been tasked to provide the essential safety net for member countries in need of financial support during crisis times. Neither of those functions existed in the euro area before 2010.

Thanks to these measures, the euro area now has stronger institutions to prevent and manage a potential future crisis. But the reform agenda is not finished, and it is being advanced as we speak in several important directions. Just last December, the Heads of State and Government endorsed a package of reforms to further strengthen the resilience of the euro area. The further development of the ESM is an important part of this reform package, and we are already hard at work to implement this new mandate. Further important steps are envisaged, in particular, to complete the banking union and create a euro area budget.

The ESM will be strengthened as a crisis resolution mechanism. It will provide a backstop for the Single Resolution Fund (SRF) that will be introduced at the latest by 2024. In close cooperation with the European Commission, the ESM will also take a stronger role in the design, negotiation and monitoring of financial assistance programmes. In addition, the eligibility process for the ESM’s precautionary credit lines will be more transparent and predictable. We want to make it easier to prevent contagion across the euro area.

Europe is also working towards the completion of the banking union. The common backstop for the SRF is one important step. In addition, the creation of its missing third pillar – the common deposit insurance scheme – and the conditions for taking this step are currently being discussed. Completing the banking union will support the creation of pan-European banks operating across countries. This will increase risk diversification, support growth through better allocation of resources, and allow banks to reduce costs by exploiting synergies.

In the same vein, further efforts are needed to create a capital markets union in Europe. The European Commission has followed up on all initiatives it had suggested under this agenda. And some important steps have been taken towards the adoption of directives and regulations, especially in recent months. But this agenda has to be carried forward, also in view of Brexit. Larger capital markets would increase and diversify sources of funding, enhance private risk sharing, create new opportunities for investors, and make markets work more effectively, especially across borders. At the same time, care needs to be taken to not fall behind the curve on managing risks, such as from less regulated financial sectors and new technological developments, including cyber-risk.

Furthermore, the introduction of a euro area budget is envisaged to support convergence and competitiveness among euro area countries. Convergence reduces the risk of macroeconomic and financial imbalances, while competitiveness strengthens the growth potential and stability of the economies. The plans currently under discussion therefore add to the overall resilience of the euro area.

I have outlined a number of external and internal risks that can affect financial stability in Europe, and against which we must be—and I can assure you, we are—vigilant. However, I want to stress that the fundamentals for continued growth in Europe, and the euro area in particular, remain in place.

And if you consider the extensive institutional reforms carried out in recent years in Europe, you can see that policy makers have shown the capacity to learn and change, and to address the vulnerabilities that threaten financial stability.

Thank you for your attention.

Author

Contacts