Taking stock of the euro area’s pandemic response

It’s been over a year since most of Europe went into an unprecedented lockdown to stop the spread of the coronavirus and many European countries are still struggling with a third wave of the pandemic. Nevertheless, accelerating vaccinations seem to be raising prospects for sustained containment and the economic outlook has brightened, as the EU’s recent spring forecast shows.

At the onset of the pandemic, government measures to buffer their economies were complemented by swift EU support of furlough schemes for workers and liquidity support for companies. In addition, the Recovery and Resilience Facility was launched to make the EU greener and more digital. At the national, and even more so at the European level, these measures embodied a two-pronged strategy: closing the economic and financial gap caused by the pandemic through temporary, targeted measures on the one hand, and encouraging a strong, lasting recovery on the other hand.

The strategy has been broadly successful: all euro area countries are expected to reach the pre-pandemic (end-2019) level of GDP either this year or the next. The abovementioned forecasts further suggest that euro area countries could catch up with the pre-pandemic growth trend the year thereafter with the right fiscal and monetary strategy.

While most commentators were impressed with the speed and depth of the EU’s response to address the pandemic, some regarded it as too tame compared with the US, despite the clear commitment of governments to continue supporting the economy until the pandemic crisis has been overcome. In this blog post, we argue that this is not the case, the EU response was and remains adequate and comparisons between the EU and US responses solely based on the size of the stimulus do not take into account the different social security systems and approaches to support individuals and firms in need.

Unemployment and bankruptcies contained

Contrary to other regions around the world, most EU countries have extensive social security systems. Therefore, additional, discretionary fiscal measures could focus on complementing and expanding the existing systems to minimise lasting damage to the economy (scarring) by providing firms with liquidity and enabling workers to keep their jobs.

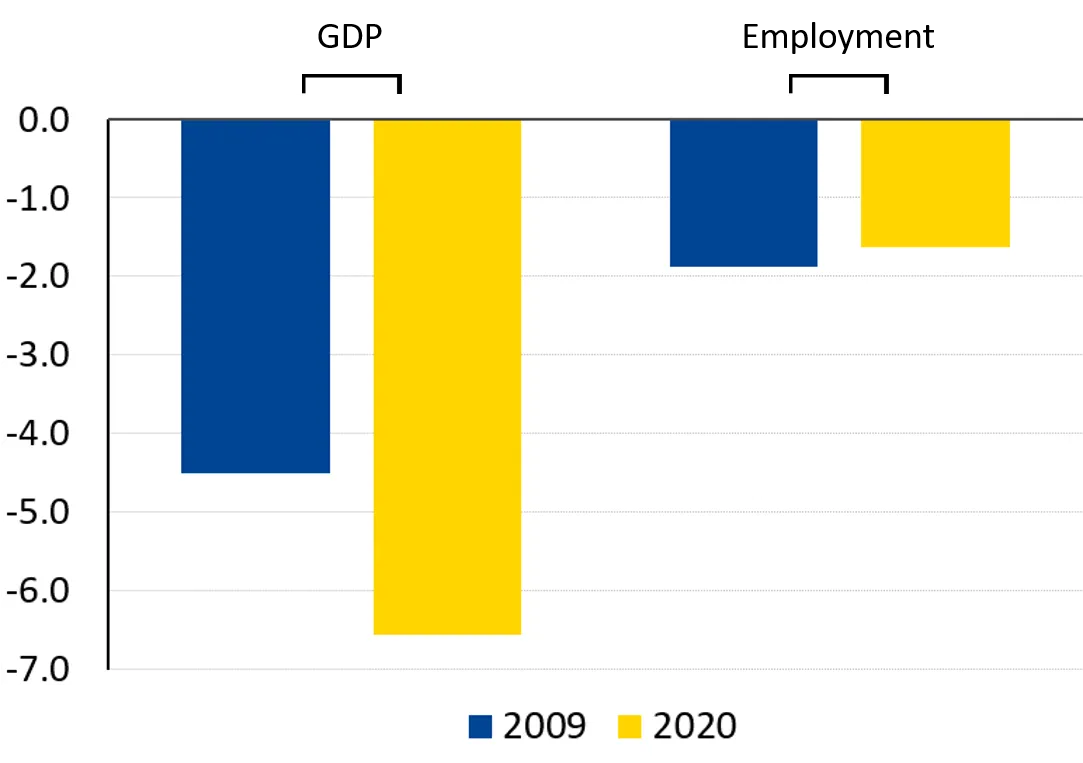

These timely, temporary and targeted measures brought strong relief to labour markets. At times, up to 30% of the EU workforce was covered by job retention schemes, which meant that the unemployment rate in the EU remained much lower this time than in past recessions.

Figure 1: GDP and employment growth in the EA: 2009 vs 2020 (% yoy)

Sources: Eurostat, European Commission (AMECO database)

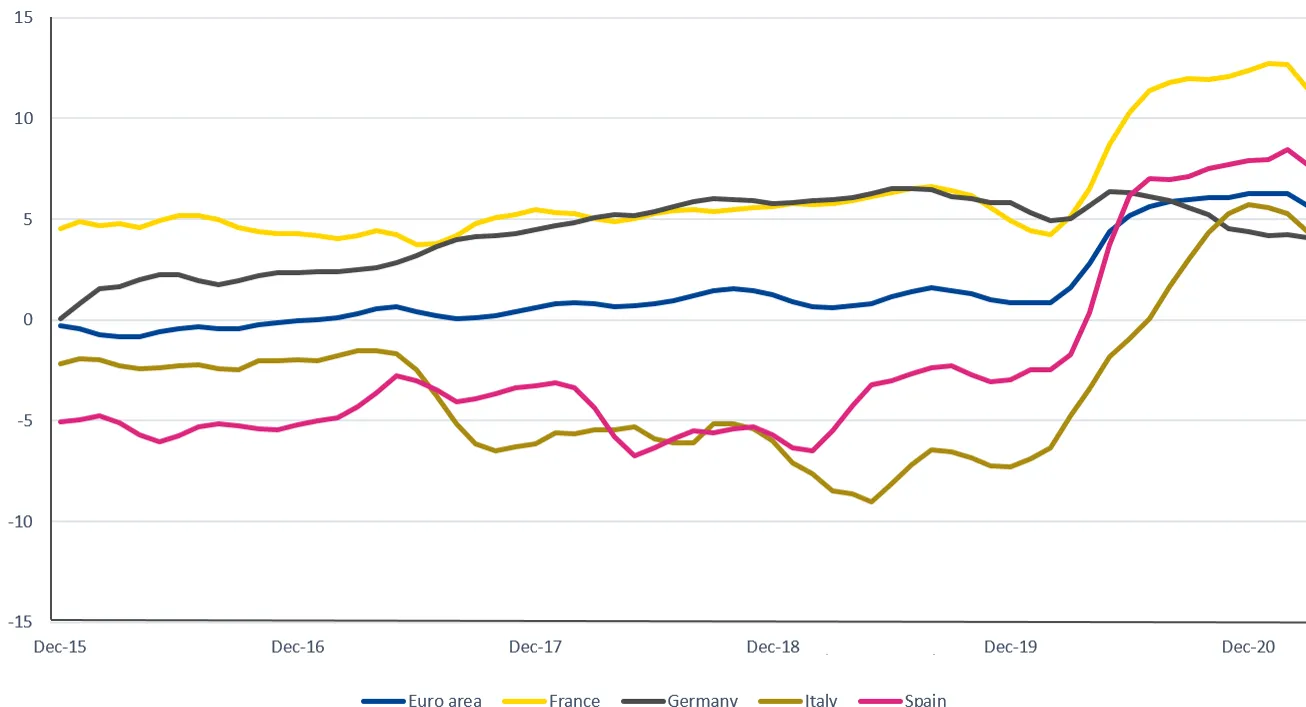

In the corporate sector, bankruptcies and loan defaults were contained as firms benefitted from ample liquidity provision through monetary policy, macro-prudential relief and public guarantees which supported sizable bank credit extensions in 2020.

Figure 2: Loans to non-financial corporations (% yoy, 3 month average)

Source: Haver & the European Central Bank. Monetary financial institutions assets: loans to domestic non-financial corporations (NFC).

In total, national governments and EU initiatives (including the ECB’s bond purchasing programme) unlocked €3.7 trillion of support in 2020. Some of them, such as the Next Generation EU programme, will be rolled out from this year onwards. At the same time, national governments have extended their fiscal measures and will keep them in place and increase the available fiscal support if the economy does not recover as swiftly as expected.

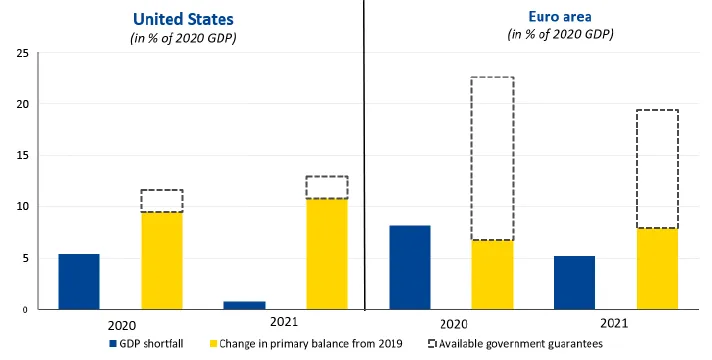

There is a strong consensus among euro area governments that this extensive budgetary support continues to be warranted. Overall, fiscal support in 2021 matches the shortfall of GDP compared to the pre-pandemic trend (see figure 3). In addition, European governments continue to offer public guarantees in support of company funding and the EU will start disbursing funds under the Next Generation EU programme.

Figure 3: Post-2019 GDP shortfall & available fiscal support: US and euro area

Source: Source: ESM based on EC, Eurostat and IMF

Notes: The GDP shortfall is measured as the difference between euro area GDP forecast for 2020 and 2021 by the European Commission in autumn 2019, and the actual euro area GDP by the European Commission in spring 2021, expressed as a percentage of the 2020 GDP. The primary balance captures the change in compared to 2019. For 2020, available government guarantees in the euro area refer to the total envelope of government loan guarantees. For 2021, the available guarantees are calculated as the difference between the total available envelope and the take-up in 2020 as guarantee commitments continued. They are expected to expire in the course of 2021 unless prolonged further. In the US, the total envelope for both years includes $454 billion to backstop section 13(3) Federal Reserve facilities that purchase corporate obligations in the primary or secondary market (source: IMF Monitor, April 21).

Despite these extensive EU measures which are keeping many companies in business and workers in employment, some critics maintain that they fall far short of the US government’s support to the economy. We would like to point out that the fiscal measures on both sides of the Atlantic were both sizeable, but in fact very different in nature.

While the EU’s strategy is more focused on supply-side support, US fiscal policy, including US President Joe Biden’s recent package, places a stronger emphasis on demand-side measures, such as direct income support in the form of cash handouts. This supports aggregate demand and creates what some economists call a “high-pressure economy”.

There are several reasons why this may not be an adequate policy response in the EU. First, to some extent, the US policy choice reflects the lack of a broad social safety net that provides an effective shield against hardship, including in a crisis. Second, more targeted measures – particularly when focused on those in need through social security schemes – may provide more “bang for the buck” in terms of consumption. Broad measures risk having a limited impact relative to the large overall size of resources spent, as a significant portion of the support may end up in private savings. It is uncertain whether these savings will be spent to contribute to the recovery.

A more effective use of public funds also matters because not all European countries have the same fiscal space as the US, which has relatively low tax rates. It also benefits from the “exorbitant privilege” of being the world’s primary reserve currency, i.e. it faces less constrains in raising debt on the market than European countries.

Finally, there is a risk that a deliberately oversized fiscal push may lead to a harsh landing when the stimulus is withdrawn. This risk may be mitigated in the US if the big investment programme proposed by the Biden administration - assuming it really will be adopted and implemented over the next 10 years - is largely tax-financed. Additional deficit spending would heighten the risk of inflationary over-stimulus, which will emerge in the coming years and could trigger a marked, and potentially recessionary, monetary policy response.

As mentioned above, the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility is oriented towards boosting the supply-side of the economy and aims to effectively improve long-term growth with a combination of investment and policy reform. A significant percentage of funding is earmarked for reducing carbon emissions and boosting digitalisation. At the same time, private sector investments and the creation of new firms can be supported through capital transfer schemes. Country-specific recommendations further facilitate labour and product market improvements. Overall, we can see a broad range of tools employed by the EU to encourage sustainable growth.

Therefore, we firmly believe that the euro area is on the right track and that that the comprehensive EU and national economic policy responses to the pandemic are as adequate today as they were when they were launched last year. In this low-interest rate environment - which is not expected to reverse to levels seen before the euro was created - fiscal support is and remains adequate and higher debt levels are manageable.

The next steps

That said, policy-makers will face important challenges in the coming months, as economies bounce back and the need for broad, general support wanes. Governments need to formulate credible, medium-term growth strategies and at the same time chart a fiscal path over the coming years to stabilise and decrease debt and create fiscal space to address future needs.

Therefore, the most important question is how much and what kind of fiscal support is still needed to address the pandemic-induced GDP shortfall, while at the same time promoting a lasting recovery and preventing longer-term scarring of our economies.

While stimulus through automatic stabilizers can easily be adjusted, there is a risk of friction and cliff effects when the discretionary fiscal support is halted. The latter includes measures to facilitate bank financing of companies, which should not be withdrawn abruptly. Instead, continued public support which goes hand in hand with private sector initiatives will help to direct investment and capital support towards the sectors and companies with the highest growth potential for a lasting recovery. Going forward, increasing private risk sharing, for example through cross-border investments, will also strengthen the overall resilience of the euro area.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Brenda Nolden and Markus Rodlauer for their valuable contributions to this blog.

Further reading

Gergely Hudecz, Rolf Strauch, Thomas Wieser (2020), Addressing the risk of regional disparities

Nicoletta Mascher, Rolf Strauch (2020), A stronger banking union for a stronger recovery

Hoe Ee Khor, Rolf Strauch (2020), Same crisis, different responses to Covid-19

Kalin Anev Janse, Siegfried Ruhl (2020), Why the Covid-19 credit line still makes sense

Jaroslav Baran (2020), How Europe’s pandemic response reduced market uncertainty

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Authors

Blog manager