Labour hoarding – euro area’s achilles heel?

A robust labour market has buoyed euro area resilience through recent economic shocks, but this may be short-lived. Despite significant drops in economic activity during the Covid-19 pandemic and the recent energy crisis, and continued weakness thereafter, employment growth remained robust. This divergence led to a fall in labour productivity as firms hoarded labour, keeping more employees than economic activity warranted.

Rising labour costs is one of the factors that threaten firms’ competitiveness, necessitating future employment adjustments to avoid being priced out of the market. Labour hoarding coupled with structural and persistent low growth could eventually result in increased unemployment, undermining resilience and impacting the economy, public finances, and financial stability – key concerns for the European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

The dynamics change between employment growth and economic activity

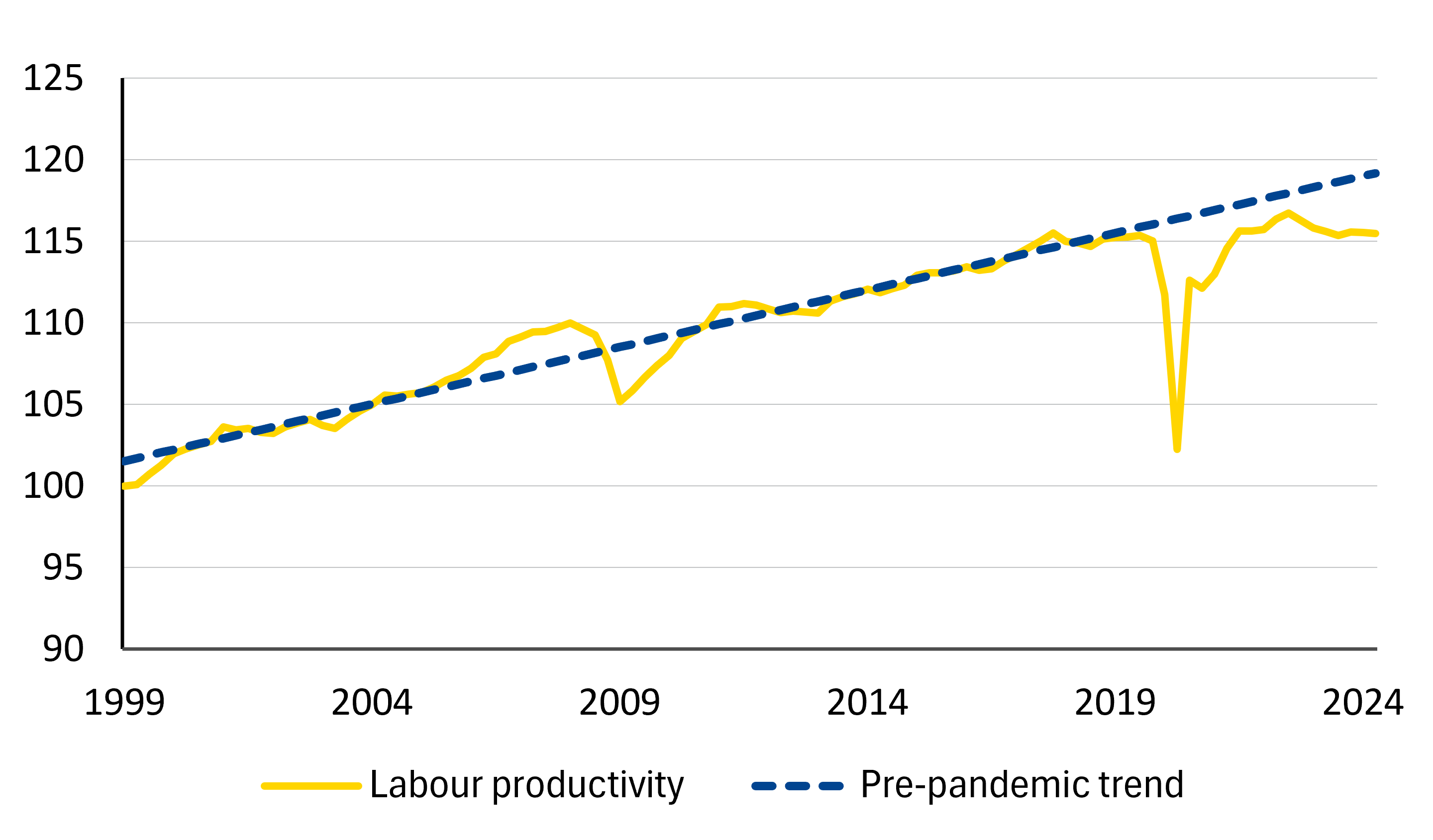

Over the past few decades, economic activity and total employment grew in tandem, with economic activity expanding slightly faster. This trend has led to steady growth in labour productivity (see Figure 1) [1] as more goods could be produced per worker on average. The industrial sector has generated significantly more output with fewer employees compared to the broader economy, with labour productivity growth on average almost three times higher than the rest of the economy over the two decades preceding the Covid-19 pandemic.

Figure 1: Labour productivity remains below its long-term trend

(Gross value added per employment, Index 1999 Q1=100)

Notes: The yellow line represents labour productivity as measured by gross value added divided by total employment normalised to Q1-1999=100. The dashed blue line shows the pre-pandemic trend using data up to Q4 2019.

Sources: Eurostat and ESM calculations

Typically, labour productivity falls during economic crises and recovers afterwards, with activity growing faster than employment. However, this dynamic has changed.

During the pandemic, job retention schemes protected employment while activity dropped considerably, leading to an unusually sharp decline in labour productivity per employee, although productivity per hours worked remained stable. [2] Similarly, with the energy crisis, employment has consistently outperformed economic activity, even during the current recovery phase.

Since the second half of 2022, growth in both hours worked and employment has decoupled from economic activity, particularly in the industrial sector. At the same time, the unemployment rate in the euro area reached historical lows, with firms hoarding workers. Labour market stabilisation measures had kept employment high, but firms also voluntarily maintained higher employee levels than usual. Several surveys reported labour shortages, as the high demand for labour could not be met. Overall, a record share of firms posted vacancies, indicating a tight labour market.

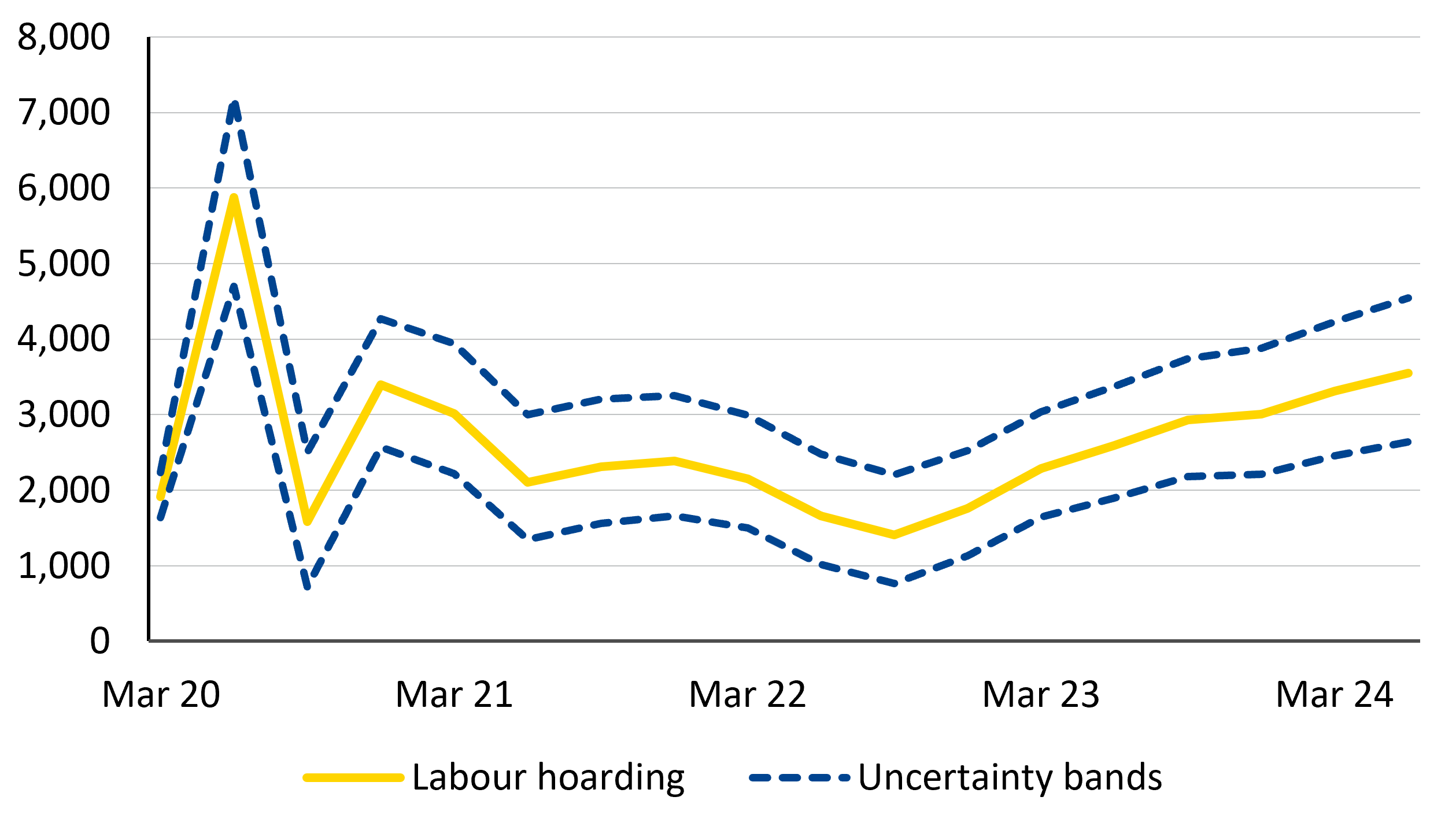

Labour hoarding is still high

According to our estimates, labour hoarding is keeping current employment levels 2.1% higher than they would have been otherwise. We capture labour hoarding by analysing the historical relationships between economic activity and employment before the pandemic and extrapolating this using post-pandemic realised activity.[3] Comparisons between the extrapolated levels of employment and the current ones reveal the extent of labour hoarding. As of the second quarter of 2024, our estimates indicate that employment is about 3.6 million workers above the level implied by economic growth (see Figure 2). Without labour hoarding, we calculate the unemployment rate would be about two percentage points higher.[4]

Figure 2: Labour hoarding high during pandemic and again on the rise

(the number of employees in thousands)

Notes: The yellow line reflects the estimated number of employees that firms hoard. The blue dashed lines reflect the estimation uncertainty (16th and 84th percentiles).

Source: ESM calculations

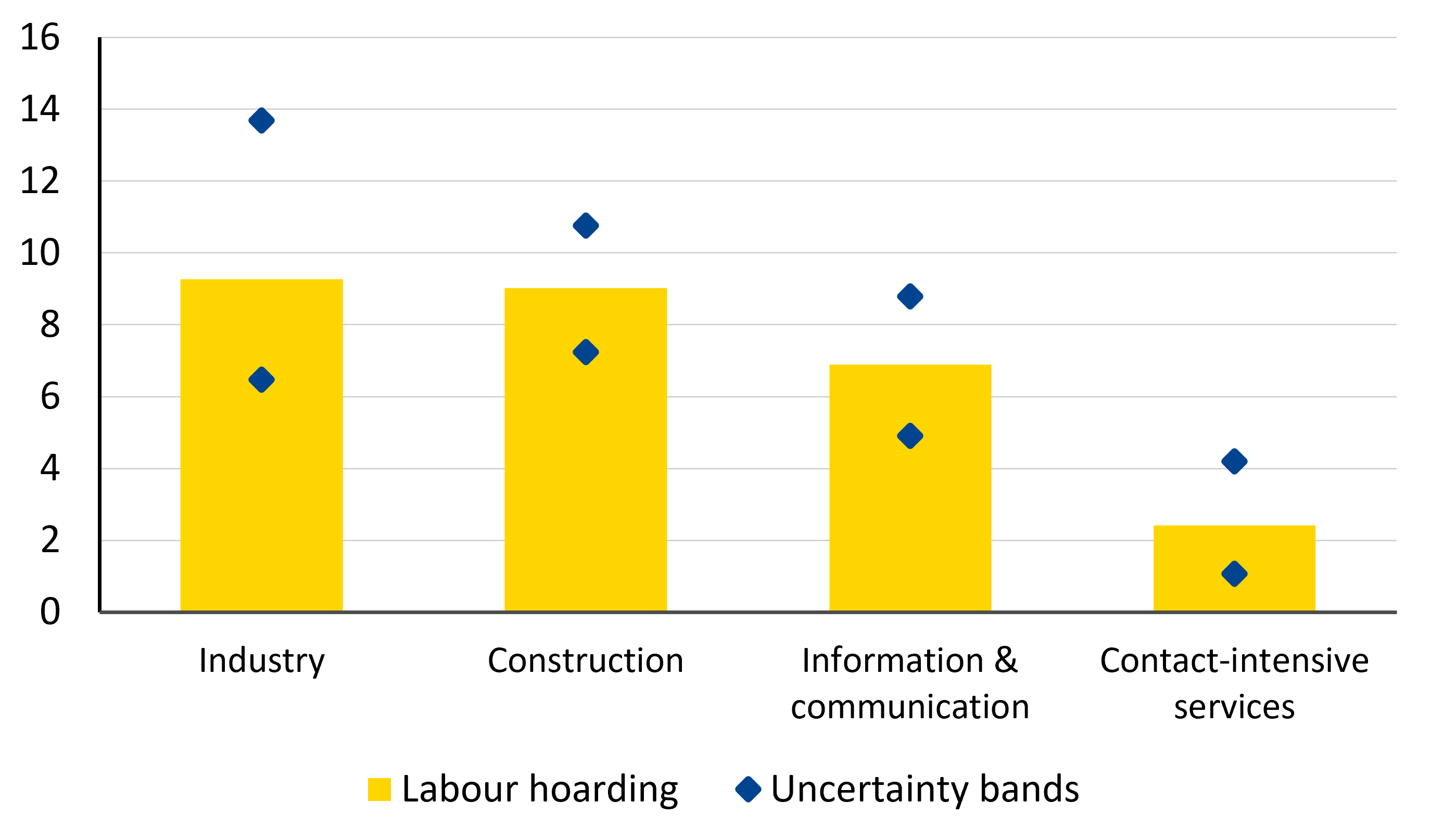

Labour hoarding varies across euro area countries and economic sectors, with significant impacts in the industrial and construction sectors (see Figure 3). In the industrial sector, the historical relationship between employment and economic activity suggests that employment levels in the second quarter of 2024 should be 9.3% lower than current levels in that sector (equivalent to 1.3% of total employment in the economy). In contrast, labour hoarding in the services sector accounts for 2.3% of employment in that sector.[5] In the euro area, Germany and France are (significantly) driving the phenomenon of labour hoarding. Employment levels in these countries are approximately 7% and 5% higher, respectively, than they would be without hoarding.

Figure 3: Some sectors show strong signs of labour hoarding

(% of sectoral employment, as of Q2 2024)

Notes: The bars reflect the estimated number of employees that firms hoard in each sector. The dots reflect the estimation uncertainty (16th and 84th percentiles).

Source: ESM calculations

Cyclical and structural factors can drive labour hoarding. Firms have some buffers from above-average profit growth in recent years, which can temporarily absorb higher labour costs by maintaining high employment levels. [6] This, then, supports labour hoarding. The anticipated economic growth would boost productivity, causing labour hoarding to dissipate naturally. Structural factors, such as an ageing population and scarcity of available workers, could also motivate firms to maintain higher employment levels.

Risk of employment adjustments if activity proves weaker than expected

Looking ahead, stronger economic activity is expected to drive the recovery of productivity. Effectively, however, the projected recovery is rather modest and faces downside risks, which poses a risk of employment adjustment forward looking. Prolonged high labour costs and the depletion of profit buffers could lead to employment reductions to achieve labour productivity growth. Labour hoarding could then translate into increased unemployment, a risk we try to quantify with our estimates.

The realisation of a potential employment shortfall poses risks to aggregate demand, public finances and, potentially, financial stability. Additional unemployment support would strain public finances. Higher unemployment often brings higher credit risks for banks emerging from households and corporates.

Labour market developments are crucial for policy makers as they highlight two key challenges ahead. First, the urgent need to address the structural challenges exacerbated by the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis, which contribute to the weak economic recovery, particularly in the industrial sector. Recent reports by Enrico Letta and Mario Draghi outline a clear medium-term agenda to tackle these challenges. Second, active labour market policies can be designed to facilitate the smooth and efficient reallocation of workers to more dynamic and productive sectors across Europe. This can gradually reduce existing labour hoarding while supporting growth.

Though the labour market has buttressed euro area resilience against the economic shocks of the Covid-19 pandemic and energy crisis, this resilience may only be temporary if economic weaknesses turn structural. Policy action can help to prevent an employment shortfall and, ultimately, strengthen public finances and financial stability.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Pilar Castrillo and Rolf Strauch for the valuable discussions and contributions to this blog post, and Raquel Calero for the editorial review.

Further reading

Botelho, V. (2024), “ Higher profit margins have helped firms hoard labour ”, ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 4/2024.

Footnotes

About the ESM blog: The blog is a forum for the views of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) staff and officials on economic, financial and policy issues of the day. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the ESM and its Board of Governors, Board of Directors or the Management Board.

Authors

Blog manager