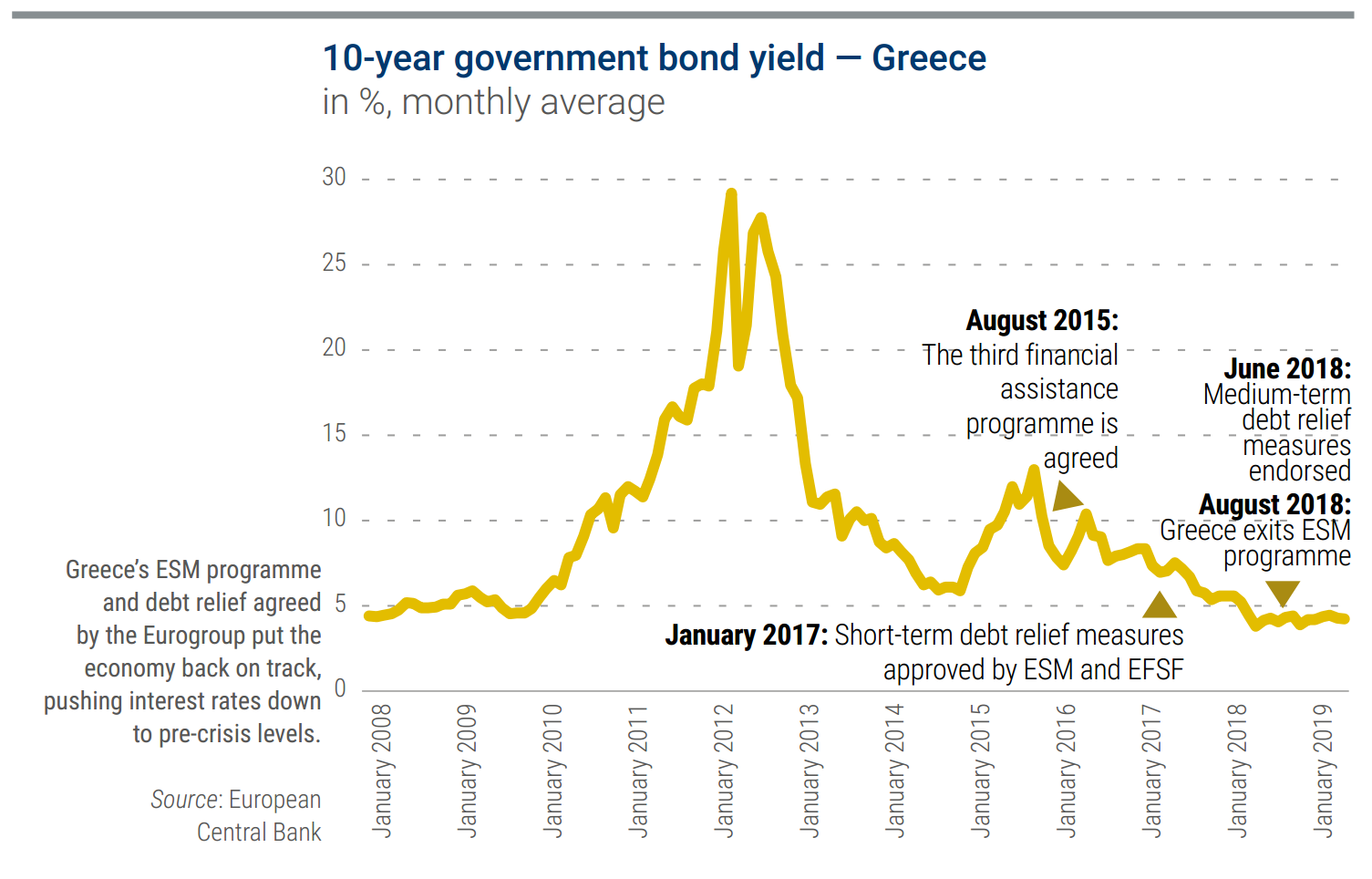

Greek banks were shut and in need of cash when the government at last requested a third programme. On 10 July 2015, a Friday, the European Commission and the ECB responded favourably to the Greek request for an ESM loan, warning that ‘an uncontrolled collapse of the Greek banking system and of Greece as a sovereign borrower would create significant doubts on the integrity of the euro area as a whole’[1].

But the flipside was that some of Greece’s fellow euro countries were at their limit. On that same day, a proposal was circulating out of Germany that suggested Greece should leave the euro if it wouldn’t agree to more stringent reforms. Commission President Juncker had said earlier in the week that the EU had a Grexit plan ‘prepared in detail’[2], but he had continued to advocate Greece’s place in the monetary union. The Friday proposal, shown to a select group of high-ranking officials, made it clear that leaving the euro, at least temporarily, was now on the table[3].

Over the course of the weekend, negotiations would lead to an overnight debate to decide Greece’s fate – and if euro membership was as irrevocable as promised. In the end, Greece and the common currency would remain joined, but the path would not be easy.

On Sunday 12 July, European leaders gathered for another summit that would prove to be the deciding moment for Greece’s membership in the euro. The talks stretched on for hours. Tsipras met at least four times with the EU’s Tusk, France’s Hollande and Germany’s Merkel. Around 6.00, Merkel, Hollande, and Tsipras were ready to throw in the towel, but Tusk refused to let them step out of the room. ‘Sorry, but there is no way you are leaving this room,’ the former Polish prime minister said, according to a report in the Financial Times[4].

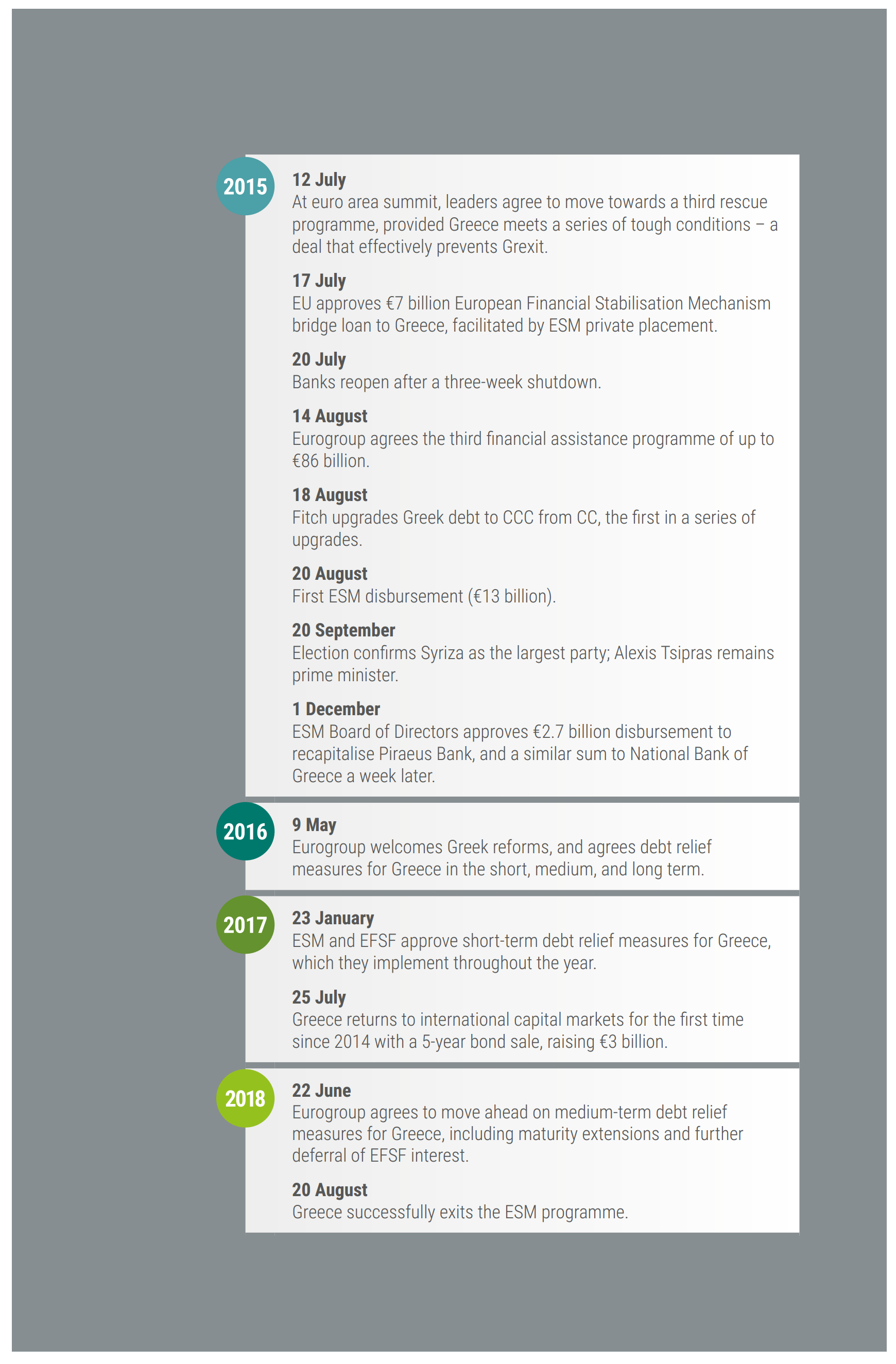

The talks resumed. After intense negotiations, the member states decided on Monday morning to move towards a third rescue programme, provided that Greece met a host of tough conditions. To allow time for these criteria to be met, the EU also prepared for a bridge loan that would tide Greece over until it could get its full programme up and running. The combination of the bridge loan and the next rescue would prevent Grexit, once the measures could be put in place.

Euro area leaders set out a list of ‘minimum requirements’ for proceeding with the talks.[5] Just to start the process, Greece was granted 10 days – until 22 July[6] – to pass legislation to broaden the tax base, streamline value added tax procedures, reform the pension system, ensure the independence of the statistical agency, implement EU budget oversight rules, update its Code of Civil Procedure, and enshrine the EU’s directive for handling bank failures in national law[7]. Greece would also need to commit to seeking further IMF aid in 2016, when its existing programme was due to expire.

The impositions were necessary because of ‘the need to rebuild trust with Greece,’ as the 12 July summit statement[8] put it. Further aid was contingent on Greece grasping that the reforms were in its own interest, as then-German Finance Minister Schäuble explained. ‘If there is no ownership on the part of the government, it cannot work,’ he said, noting that, with Greece, there was ‘always the risk that decisions may not be implemented with sufficient determination or that they get watered down. A certain degree of basic support among the population is necessary as well.’

In the subsequent negotiations with the institutions, Greece was required to pursue ambitious further pension reforms, strengthen its banking sector, privatise its electricity transmission network, deregulate ‘closed’ professions such as ferry transport, modernise its labour bargaining system, and set up a fund to generate €50 billion from state-owned assets[9].

During those critical July days, Greece faced a serious cash crunch. Being late sending money to the IMF would prompt a scolding, while defaulting on an upcoming payment to the ECB would automatically shut off Greece’s access to funds. But, with ESM funds not yet available, how could Greece find the money it needed in the interim?

The solution came from the Commission’s European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM), which had been used early in the crisis to help Ireland and Portugal. It had since been idle, but remained a suitable vehicle to provide a bridge loan to tide Greece over.

Unlike the ESM, run by euro nations with a stake in the currency’s stability, the EFSM is managed by the entire EU and underwritten by the EU budget. This meant securing the agreement of nine additional EU Member States, which were not part of the euro area. The UK held out[10]; after voluntarily participating in some of the first cobbled-together responses to the euro crisis, its politicians wanted nothing to do with Greece’s latest travails.

As a workaround, the EU’s civil service drafted plans to protect the non-euro countries with collateral on the off-chance that disaster struck while the loan was in place. To shield euro area taxpayers from potentially footing the collateral bill, the loan was based on central bank profits from holdings of Greek bonds, which had been promised to Greece and could be rerouted to cover an unexpected loss. This broke an impasse between the UK and the euro area.

As it happens, the ESM has been a central part of managing these profits since the Eurogroup agreed to set them aside for Greece. In 2013, Jasper Aerts, an ESM legal officer who would later become deputy general counsel, helped design the system for the ESM to hold and monitor these funds. The firewall has worked closely on the use of these funds with euro area member states and the ECB over the years, as well as on this detail of the bridge loan. ‘Both at the back and in the front, the ESM was involved in this innovative piece of financial engineering,’ Aerts said.

Once the EU Member States approved the bridge loan to Greece, the EFSM’s next task was to line up financing on capital markets. The Commission’s fund was designed to borrow from the markets, but it did not have a large liquidity pool on-hand and was not a regular large issuer of bonds. How would it raise €7 billion virtually overnight? The answer came from the ESM putting together a massive short-term private placement.

‘We could help in such a tight situation in a way that one might not have expected,’ said ESM Managing Director Regling. ‘We could help and were willing to do that within our standard framework.’

Under ESM guidelines, the firewall is required to invest in high-quality, short-term securities to preserve and protect its permanent capital. Since the EFSM enjoyed the exemplary credit reputation of the entire EU, which had ratings equivalent to AAA from Moody’s and Fitch, its debt was eligible for ESM investments under the firewall’s strict investment guidelines. This allowed the ESM to offer the funds quickly, sparing the EFSM a last-minute scramble for financing from the market. And it allowed Europe to focus on the key task at hand, instead of worrying where the short-term financing would come from.

On 16 July, the Eurogroup endorsed the third rescue programme in principle[11]. A day later, the 28-strong EU approved the bridge loan, with a term of up to three months[12]. Greece then used the money to pay the ECB on time and clear its arrears with the IMF.

The ESM’s role in the transaction didn’t become public until September, when it was reported in the media[13]. By that time Greece had repaid the money, and the firewall’s unusual step of showing up on both sides of the balance sheet no longer made the waves it would have in the heat of the moment. It was one of the ESM’s most important contributions to the funding chain, and one of its most unsung.

Regling said there was ‘zero doubt’ that the ESM was in a position to extend the financing that would, in turn, allow the three-week bridge loan to go forward.

‘It was certainly something exceptional – we don’t usually invest €7 billion in a single week,’ he said. ‘We used the scope that we had because it was in everyone’s interest. It was in our interest, as Greece’s largest creditor, that the country get out of this status of a “defaulting” country.’

After a three-week shutdown, Greek banks reopened on 20 July[14]. The capital controls remained in place, but getting the banks open again was a crucial step towards restoring Greek financial stability.

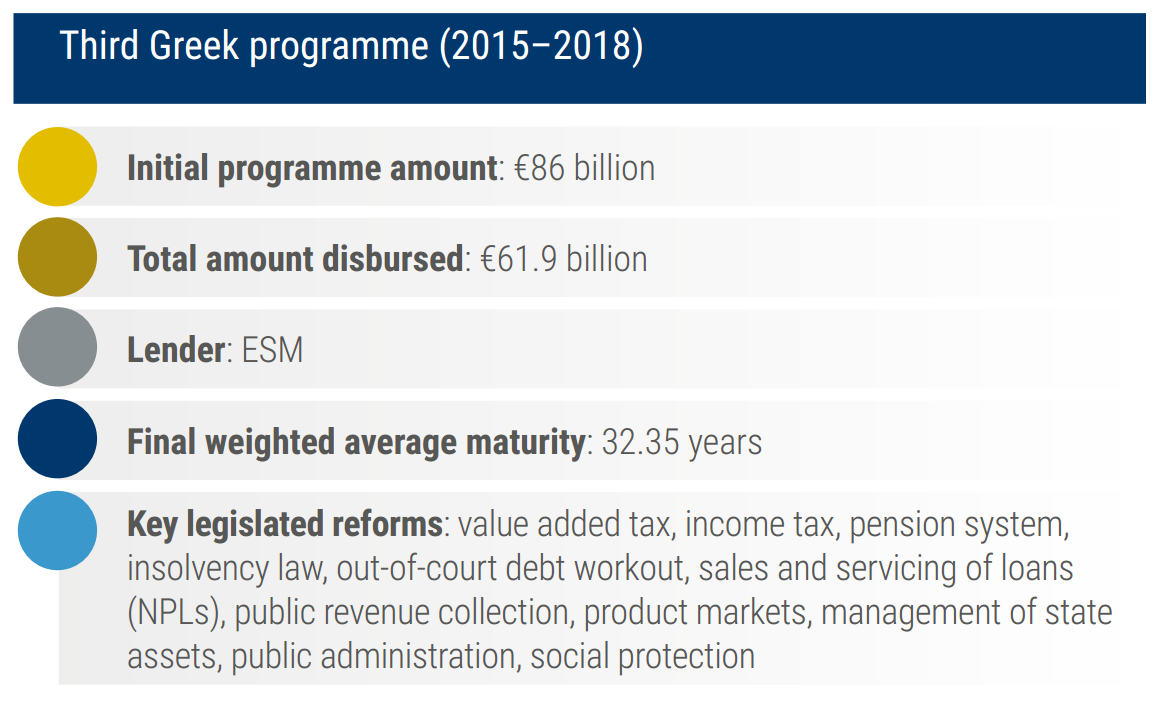

Greece’s third euro area financial assistance programme was finally approved on 14 August 2015[15]. It envisaged a financing envelope of up to €86 billion, including up to €25 billion to recapitalise the banks and a cushion for unexpected needs. In contrast to past programmes, in which the ESM had played a supporting role, the firewall became an active participant in the negotiations.

‘It was a logical step for the ESM to become closely involved in the negotiations concerning financial support,’ former Eurogroup chief Dijsselbloem said. ‘The knowledge and expertise on beneficiary countries and on financial markets, as well as the specifics of the ESM toolkit are valuable in discussions on the implementation of support programmes.’

For its part, the IMF stepped back. Voicing concerns about Greece’s long-term debt outlook, the IMF declined to contribute financially to the third programme, although it would later, in 2017, agree to a stand-by arrangement to be in place through the end of the ESM package[16].

On 18 August 2015, Greece began to reap market benefits, earning a Fitch upgrade to CCC from CC. On 20 August[17], the ESM approved the first programme tranche, a €26 billion lump sum that included €10 billion for the banks and money to pay back the bridge loan[18]. Securing the payouts from this tranche would be another tightly managed process, contingent on Greece carrying out reform pledges over time. Greece got €13 billion in August to meet its immediate cash needs and the bank money held in reserve to be made available upon request, subject to approval by the ESM Board of Directors.

From the beginning, the euro area didn’t expect Greece to need all €86 billion in aid. For one thing, the currency union was counting on Greece eventually striking a new deal with the IMF. For another, the €25 billion envelope for the banks was an upper-end estimate. Experts including the ESM were convinced it would be a lot less, but Europe was determined to stay ahead of the markets.

‘We established this envelope of €25 billion, but without expecting that there would be anything like that amount required,’ said Hesketh, of the ESM’s banking department. ‘The worst thing to do is to come back and ask for more money.’

The ECB’s stress tests turned up a total shortfall of €14.4 billion in October under the adverse scenario but, in the end, Greek banks didn’t use up their initial €10 billion tranche. All of the four systemic banks were able to raise private capital, as two covered their capital needs entirely and €5.4 billion of ESM funds covered the residual needs of the other two[19].

With the banks back in business and in better health, Greece began to find some stability. In September, parliamentary elections confirmed Syriza as the leading party, providing much-needed political continuity.

Greece implemented sufficient reforms to obtain a €2 billion disbursement from the remaining general-purpose funds in its approved tranche in November, and it also moved ahead with the bank recapitalisation[20]. Of the two banks that required ESM assistance, Piraeus Bank received €2.7 billion on 1 December[21] and National Bank of Greece received a very similar sum a week later[22].

It was important for the Greek bank recapitalisation to take place before new European bank rescue rules went fully into force at the start of 2016. The new rules, known as the bank recovery and resolution directive, specify the circumstances in which public funds can be used to assist banks in distress. A core principle of the directive is that public funds cannot be used before a minimum of 8% of the bank’s liabilities are bailed in to cover capital shortfalls.

The Greek banks had very few liabilities outstanding following the private sector involvement of 2012, meaning they would have had to bail-in uncovered deposits of more than €100,000 to achieve the minimum bail-in requirement. As these deposits were mainly held by small businesses rather than rich individuals, there was a strong concern that in this case bail-in could be financially destabilising for the economy and counter productive.

The flexibility of the older framework meant that Greek banks had an extra safeguard when they went to the markets to raise capital. Had the recapitalisation effort failed, the banks might have been able to work with regulators more flexibly than under the rigid structure that would be required later on.

Greece obtained another €1 billion of the first tranche in late December 2015[23]. From there, Greece tackled reforms step by step, winning approval in May 2016 for a €10.3 billion second tranche and in June 2017 for a third tranche of €8.5 billion[24]. Greece also regained favour with the IMF, thanks to its reforms and Eurogroup pledges of future debt relief. The IMF approved in principle a €1.6 billion stand- by arrangement[25], although it ran until 31 August 2018 without Greece drawing on it because of ongoing IMF concern over debt sustainability.

When Greece unlocked a disbursement in March 2018, it was hailed as a sign that the programme would conclude on a high note. Valdis Dombrovskis, the European Commission’s vice president for the euro and social dialogue, said the step strengthened confidence in the Greek economy. ‘Moving closer to the end of programme, Greece’s interest is to show that it has reached the point of no return’,[26] he said.

As the programme wound down, Greece twice tapped the bond market, burnishing its credibility with investors. On 25 July 2017, it raised funds on the market for the first time in three years, selling €3 billion in 5-year bonds[27]. Greece borrowed another €3 billion with the sale of 7-year bonds on 8 February 2018.

‘Greece’s approach is what we’ve seen in the other countries that went through a programme – they did not wait until the last day of the programme to return to the market,’ Regling said. ‘After so many years of market absence, it’s important to go back slowly’[28].

In parallel, the Greek government gradually loosened the capital controls it had imposed in June 2015 to prevent money from draining out of the country.

Greece’s cumulative efforts over eight years – topped off by 450 policy steps during the ESM programme alone, as tallied by the Portuguese finance minister, Mário Centeno, who took over as head of the Eurogroup in January 2018 – led to a 22 June 2018 Eurogroup declaration that the country would soon be on its own again.

At a conclusive meeting in Luxembourg, euro area finance ministers welcomed Greece’s completion of 88 final policy actions, accepted Greece’s commitment to further fiscal and structural reforms, authorised a final ESM disbursement, and came through with previously promised medium-term debt relief for Greece.

The wrapping up of the programme was the occasion for relief and reflection, mingled with self-criticism. ‘We have managed to deliver a soft landing of this long and difficult adjustment,’ Centeno told a press conference[29]. ‘There will be no follow-up programme in Greece.’

In a later interview with Spiegel Online, Regling looked back at the crisis management learning curve. ‘It would be arrogant to say we did everything right in Greece,’ he said. ‘There was no script for this crisis, the worst since the Great Depression’[30]. He said that a decision to conduct the bond writedowns earlier, instead of waiting until 2012, could have subdued the crisis more quickly. Regling also expressed appreciation for the Greeks’ self-sacrifice in order to stay in the euro area, saying: ‘I wish that this adjustment was more appreciated in Germany.’

On 6 August 2018, the ESM made its fifth and final disbursement to Greece, a sum of €15 billion to be used for debt service and the build-up of the government’s cash reserve[31].

When the programme formally ended on 20 August 2018, Greece was projected to have €24 billion in cash, enough to cover around 22 months of the government’s financing needs – and giving it more time to cultivate the confidence of market investors.

During the three-year programme, Greece borrowed €61.9 billion from the ESM, well below the maximum €86 billion that had been authorised by the ESM Board of Governors. Combined with earlier support of €52.9 billion from the Greek Loan Facility and €141.8 billion from the EFSF, plus €32.1 billion from the IMF in parallel with those two programmes, Greece obtained emergency loans worth about €289 billion over eight years, a sum without parallel in modern financial history.

Greece has made significant progress, said Camilleri, Malta’s representative in the working group of finance ministry deputies, hailing the reforms undertaken in recent years. At the same time, he said, the Greek government and the institutions still need to tackle many issues and to address the social dimension of the adjustment, showing that the situation remains grey instead of black or white. ‘That is where the worth of the institutions and matching governments really have to withstand a very real and significant test – when you’re faced with significantly more difficult issues and challenges,’ Camilleri said. ‘Let’s not forget the people, because ultimately every adjustment programme has a human face.’

A host of statistics document Greece’s progress from the early depths of the crisis. An economy that shrank 5.5% in 2010 grew 1.4% in 2017; a budget deficit of 15.1% in 2009 turned into a surplus of 0.8% in 2017; the current account deficit narrowed from 12.5% in 2009 to 0.9% in 2017.

Employment, always a lagging indicator, gradually turned the corner, although the improvement was partly due to emigration and declining workforce participation. Rising joblessness was, in part, a direct but unavoidable result of the reforms that were essential to modernising Greece’s economy. In order to clean up its finances, the government cut the number of civil servants by 18% between 2009 and 2015[32]. The jobless rate peaked at an average of 27.5% in 2013 and in the first half of 2018 had fallen to 19.5%.

In a speech to the European Parliament on 11 September 2018, Prime Minister Tsipras summed up Greece’s transformation. Greece ‘is a different country,’ he said. ‘Today we stand on our feet once more and look towards the future with optimism. We escaped the spiral of recession and brought the economy back on track towards growth’[33].

For the future, Greece has pledged to continue its policy of budgetary rigour, committing to a primary surplus of 3.5% of GDP until 2022 and around 2.2% from 2023[34]. Efforts must continue to strengthen bank balance sheets, render the public administration more efficient, and foster a business-friendly environment. Greece will remain under the full scrutiny of the ESM until all loans have been repaid.

‘Greece will not be on its own,’ Regling said in a video message on the day Greece regained its financial independence[35]. ‘The ESM will be a long-term partner of Greece. We have an interest that the Greek economy does well in the future.’

Focus

An unusual money market transaction

When the EU’s emergency funding vehicle, the EFSM, was authorised to provide a bridge loan to Greece, it had a top credit rating but virtually no time to raise the money on the financial markets. ‘We arranged the private placement with a very small team between the ESM and the Commission. In the end, the spirit and cooperation were exceptional,’ said ESM General Counsel Eatough.

ESM Head of Investment and Treasury Lévy remembers intense brainstorming leading up to the operation: ‘This question arose of whether we could provide €7 billion at very short notice.’ The investment team worked out the mechanics of the transaction, while the political negotiations on the bridge financing details proceeded. The EU was already on the authorised issuer list for ESM investments, and the ESM was a regular buyer of EU bonds in the market. However, investing in a private placement entailed additional logistical complications, from crafting and signing a bilateral legal agreement with the EU to making changes to the information technology system to process the transaction.

From a technical perspective, the ESM needed to decide which of its internal portfolios would be invested in the transaction and whether or not to split it into in a series of tranches. Regling agreed it would be simpler and more effective to do it all in one operation.

At one point, ESM experts wondered if the transaction was the right thing to do, but the alternative – leaving the EFSM looking elsewhere for funding as Greece teetered – was considered a greater risk. The ESM’s investment management committee set extra conditions and conducted a thorough review, making sure the investment decisions could be validated by all senior ESM staff members.

‘It was in July. There was a lot of stress around this operation,’ Lévy said. ‘Personally, I was concerned about the technical execution, because this was the biggest one-off, single-sum investment that we had ever done. So, to ensure that all aspects of the decision were taken into account, we had a full review process.’

The money market transaction, as it was eventually called, was finally underway.

On the technical side, talks between the ESM and the European Commission went smoothly. Market conditions posed a challenge, however, because short-term interest rates for an issuer like the European Commission were close to -0.20%, while the ESM was not permitted, at the time, to invest at an interest rate of less than 0%. The Commission accepted this as a condition because, even though its implied funding rate was negative, there were no readily available alternatives. The ESM also offered an early repayment option – so, while the transaction had a maturity of three months, it could be paid back as soon as the bridge financing was no longer needed, which turned out to be a matter of weeks.

‘We lent the money to the Commission, not Greece, and on the basis that it matched our own investment framework. We invested in EU paper and then we were repaid as soon as the money was unlocked,’ Eatough said. ‘If we hadn’t succeeded, it would have been game over.’

Tight timing was a hallmark of the operation. ‘We got the green light very late,’ Lévy said. ‘The money was needed on a Monday morning, but by Friday we still didn’t know whether or not the EFSM bridge loan to Greece would be approved. All of the contracts were ready and the weekend approaching, but we were not authorised to sign the documents. Luckily both the European Commission and the ESM have offices in Luxembourg.’

In the end, one of the institutions signed on the Friday night and the second one over the weekend, to make sure the effective date matched the political agreements. One of the ESM’s lawyers went to collect the signatures.

‘We took pictures with the contract signed on that day, because it was a big thing,’ Lévy said. ‘It was very exciting; we knew we were involved in something important.’

When the time came to input the amounts and account numbers into the system, there was no room for error. The ESM had to send money to the EFSM, the EFSM had to forward it to Greece, and then Greece had to make the crucial payment to the ECB. Martins was the investment team member tasked with entering the trade in the system, outside the ESM’s normal business hours.

‘We had to make sure the system was open earlier than usual, that we had front office managers, back office managers, and middle office managers there first thing in the morning,’ Lévy said. ‘As I recall, Carlos arrived at 7.00, because we needed all of the operations to be done by 8.00 or 8.30. I distinctly remember Carlos meticulously checking the screens to make sure he had all the numbers right.’

Martins knew it was a momentous step. ‘That day, that time, I decided to not simply double-check – as I usually do – but to triple-check the zeros in the transfer amount, as I was fully aware that another important page of the ESM was being written right there. And so I clicked to finalise the transfer.’

Continue reading

[1] European Commission (2015), ‘Greece – request for stability support in the form of an ESM loan: Assessment’, Online report, 10 July 2015. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/2015-07-10_greece_art_13_eligibility_assessment_esm_en1_0.pdf

[2] European Commission (2015), ‘Result of the euro summit on Greece’, 8 July 2015. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_AC-16-1834_en.htm; Euractiv (2015), ‘Juncker: We have a Grexit scenario prepared in detail’, Video, 8 July 2015. https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/video/juncker-we-have-a-grexit-scenario-prepared-in-detail/

[3] The Guardian (2015), ‘Three days that saved the euro’, 22 October 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/oct/22/three-days-to-save-the-euro-greece

[4] Financial Times (2015), ‘Greece talks: “Sorry, but there is no way you are leaving this room”’, 13July 2015. https://www.ft.com/content/f908e534-2942-11e5-8db8-c033edba8a6e

[5] Euro summit statement, SN 4070/15, 12 July 2015. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/20353/20150712-eurosummit-statement-greece.pdf

[6] Ibid.

[7] The Guardian (2015), ‘Greek parliament approves next phase in bailout reforms’, 23 July 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jul/22/greece-ecb-emergency-assistance-ceiling-raised-bailout-vote

[8] Euro summit statement (2015), SN 4070/15, 12 July 2015. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/20353/20150712-eurosummit-statement-greece.pdf

[9] Ibid.

[10] Financial Times (2015), ‘UK angered by moves to help fund Greek bailout’, 13 July 2015. https://www.ft.com/content/0c789340-296a-11e5-acfb-cbd2e1c81cca

[11] Eurogroup statement on Greece, Press release, 16 July 2015. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/07/16/eurogroup-statement-greece/

[12] EFSM: Council approves €7bn bridge loan to Greece, Press release, 17 July 2015. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/07/17/efsm-bridge-loan-greece/

[13] Bloomberg (2015), ‘EU squeezed $7.8 billion Greek bridge loan via ESM loophole’, 8 September 2015.https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-09-08/eu-squeezed-7-8-billion-greece-bridge-loan-through-esm-loophole

[14] UK, Government website (2015), ‘Greece updates: advice for UK citizens and businesses’, 29 June 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/greece-updates-advice-for-uk-citizens-and-businesses

[15] Eurogroup statement on the ESM programme for Greece, Press release, 14 August 2015. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/08/14/eurogroup-statement/

[16] IMF (2017), ‘Greece: Request for stand-by arrangement – press release; staff report; and statement by the executive director for Greece’, 20 July 2017. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2017/07/20/Greece-Request-for-Stand-By-Arrangement-Press-Release-Staff-Report-and-Statement-by-the-45110

[17] Reuters (2015), ‘UPDATE 1-Fitch upgrades Greece to ‘CCC’ after new bailout agreed’, 18 August 2015. https://www.reuters.com/article/eurozone-greece-ratings-idUSL3N10T52X20150818

[18] ESM (2015), ‘ESM Board of Directors approves first loan tranche of €26 bn for Greece’, Press release, 20 August 2015. https://www.esm.europa.eu/press-releases/esm-board-directors-approves-first-loan-tranche-€26-bn-greece; ESM (2015), ‘ESM Board of Governors approves ESM programme for Greece’, Press release, 19 August 2015. https://www.esm.europa.eu/press-releases/esm-board-governors-approves-esm-programme-greece

[19] ECB (2015), ‘ECB finds total capital shortfall of €14.4 billion for four significant Greek banks’, Press release, 31 October 2015. https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2015/html/sr151031.en.html; ESM (n.d.), ‘Greece – financial assistance’. https://www.esm.europa.eu/assistance/greece

[20] ESM (2015), ‘ESM Board of Directors approves €2 billion disbursement to Greece’, Press release, 23 November 2015. https://www.esm.europa.eu/press-releases/esm-board-directors-approves-%E2%82%AC2-billion-disbursement-greece

[21] ESM (2015), ‘ESM Board of Directors approves €2.72 billion disbursement to recapitalise Pireaus Bank’, Press release, 1 December 2015. https://www.esm.europa.eu/press-releases/esm-board-directors-approves-€272-billion-disbursement-recapitalise-piraeus-bank

[22] ESM (2015), ‘ESM Board of Directors approves €2.71 billion disbursement to recapitalise National Bank of Greece’, Press release, 8 December 2015, https://www.esm.europa.eu/press-releases/esm-board-directors-approves-€271-billion-disbursement-recapitalise-national-bank

[23] ESM (n.d.), ‘Greece – financial assistance’. https://www.esm.europa.eu/assistance/greece; Germany, Federal Government (n.d.), ‘Go-ahead for the second tranche of loans’. https://www.bundesregierung.de/Content/EN/Artikel/2016/05_en/2016-05-24-eurogruppe-einigung-griechenland-zweite-tranche-kredite_en.html

[24] European Commission (2016), ‘Compliance report: The third economic adjustment programme for Greece – first review’, 9 June 2016. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/cr_full_to_ewg_en1.pdf; ESM (2017), ‘ESM Board of Directors approves €8.5 billion loan tranche to Greece’, Press release, 7 July 2017. https://www.esm.europa.eu/press-releases/esm-board-directors-approves-%E2%82%AC85-billion-loan-tranche-greece

[25] IMF (2017), ‘IMF executive board approves in principle €1.6 billion stand-by arrangement for Greece’, Press release, 20 July 2017. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2017/07/20/pr17294-greece-imf-executive-board-approves-in-principle-stand-by-arrangement

[26] Dombrovskis, V. (2018), Tweet, 27 March 2018. https://twitter.com/vdombrovskis/status/978604388766937089?s=12

[27] Greece, Prime Minister’s Office (2017), ‘Issuance of a Hellenic Republic government bond’, Press release, 24 July 2017. https://primeminister.gr/en/2017/07/24/18369

[28] For a fuller assessment of how four programme countries approached the restoration of market access, see Strauch, R., Rojas, J., O’Connor, F., Casalinho, C., de Ramón-Lapa Clausen, P., Kalozois, P. (2016), Accessing sovereign markets: The recent experiences of Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Cyprus, ESM, Discussion Paper 2, 20 June 2016. https://www.esm.europa.eu/sites/default/files/esmdp2final.pdf

[29] ‘Eurogroup press conference of 22 June 2018’, Video, 22 June 2018. https://video.consilium.europa.eu/en/webcast/a71523e7-b839-4931-9f5b-ae7cf93ad00a

[30] Spiegel (2018), ‘Klaus Regling in interview with Spiegel Online’, 14 August 2018, ESM English translation, available at: https://www.esm.europa.eu/interviews/klaus-regling-interview-spiegel-online

[31] ESM (2018), ‘ESM disburses final loan tranche of €15 billion to Greece’, Press release, 6 August 2018. https://www.esm.europa.eu/press-releases/esm-disburses-final-loan-tranche-€15-billion-greece

[32] Eurofound (2016), ‘Greece: Reducing the number of public servants – latest developments’. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/el/publications/article/2016/greece-reducing-the-number-of-public-servants-latest-developments

[34] ESM (2018), ‘Explainer on ESM and EFSF financial assistance for Greece’, 20 August 2018. https://www.esm.europa.eu/assistance/greece/explainer-esm-and-efsf-financial-assistance-greece

[35] ESM (2018), ‘Statement by Klaus Regling on the conclusion of the ESM programme for Greece’, Video, 19 August 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5jtKFmC-Xms