17. Meeting at the opera: the leverage debate

Euro area politicians were under fire in their own countries as the crisis gained speed, which made it hard to find common ground on how next to tackle the crisis. On the one hand, the ESM was on the way and the EFSF was fully operational. On the other, each additional step towards a comprehensive firefighting approach, however incremental, was met with fierce debate.

Leaders met for a record 11 times in 2011 alone, debating how – and how far – to extend the rescue funds’ financial reach. Over the course of five formal meetings, an extraordinary summit, and one ‘informal’ meeting of the European Council, four euro area summits, they debated new tools for the EFSF and how to ensure the permanent firewall’s decision-making agility. The process would culminate in a dramatic move to make the ESM more responsive and bring forward its start date. But first they had to prepare the political ground.

Top of the agenda was the guarantee increase to unlock the EFSF’s full capacity. Germany’s Constitutional Court cleared the way on 7 September 2011, dismissing legal challenges to the temporary firewall and residual objections to the first Greek programme. The court also held that, in general, a German role in major rescue operations required the approval of either the Bundestag’s budget committee or a full plenary session.

The next step was persuading German lawmakers to grant their consent to the EFSF expansion. Regling, the EFSF’s chief executive, contributed to the debate by testifying before the German parliament.

‘It was probably useful that I was there to explain it in person,’ said Regling. A German newspaper that was sceptical of the changes ‘wrote at one point that if I had not been there, maybe it wouldn’t have gone through parliament or the hostility would have got out of control.’ Despite the endorsement by the euro area’s largest country, politics elsewhere was marked by growing resistance to the rescue programmes.

Finland added a condition to its involvement in future rescues, after the eurosceptic True Finns party surged to 19% of the vote in parliamentary elections[1]. The new government coalition insisted on obtaining collateral from aid recipients before assenting to a programme. For aid-seeking countries, putting up collateral would entail an additional cost – one that would potentially undercut a rescue package in the event that more creditor countries followed Finland’s example.

In Slovakia, the EFSF upgrade led to the downfall of Prime Minister Radičová’s government. While three coalition partners favoured the guarantee increase as the necessary price for euro membership, a junior partner, the Freedom and Solidarity Party, baulked. On 10 October, the EU urged Slovak political parties ‘to rise above the positioning of short-term politics’[2], but Radičová lost a confidence motion a day later. In the political bargaining that ensued, the opposition party Smer agreed to back the EFSF enhancements in exchange for the holding of early elections in 2012. The EFSF bill passed on 13 October. Radičová’s government went on to be defeated in the subsequent election.

With a Group of 20 summit looming in November, pressure on Europe to do more mounted from every direction. The Vix index, for instance, which measures future volatility and global risk aversion, had been elevated since August. EU countries outside the euro suffered from growing market volatility, yet had no control over euro area policy and would face the consequences of inaction or heightened crisis. Countries outside the EU were affected too.

The world was watching what tack the euro area would take; the IMF’s Lipton said: ‘It needed to be convincing enough to calm markets and avoid contagious spread of sovereign risk premia that seemed to be such a threat to other governments.’

There was no shortage of ideas for getting more firepower out of the euro area’s rescue funds. France proposed granting the EFSF a banking licence, enabling it to borrow from the ECB. But others argued that a bank-style credit line for the EFSF would intrude on the central bank’s independence and violate rules against the monetary financing of governments.

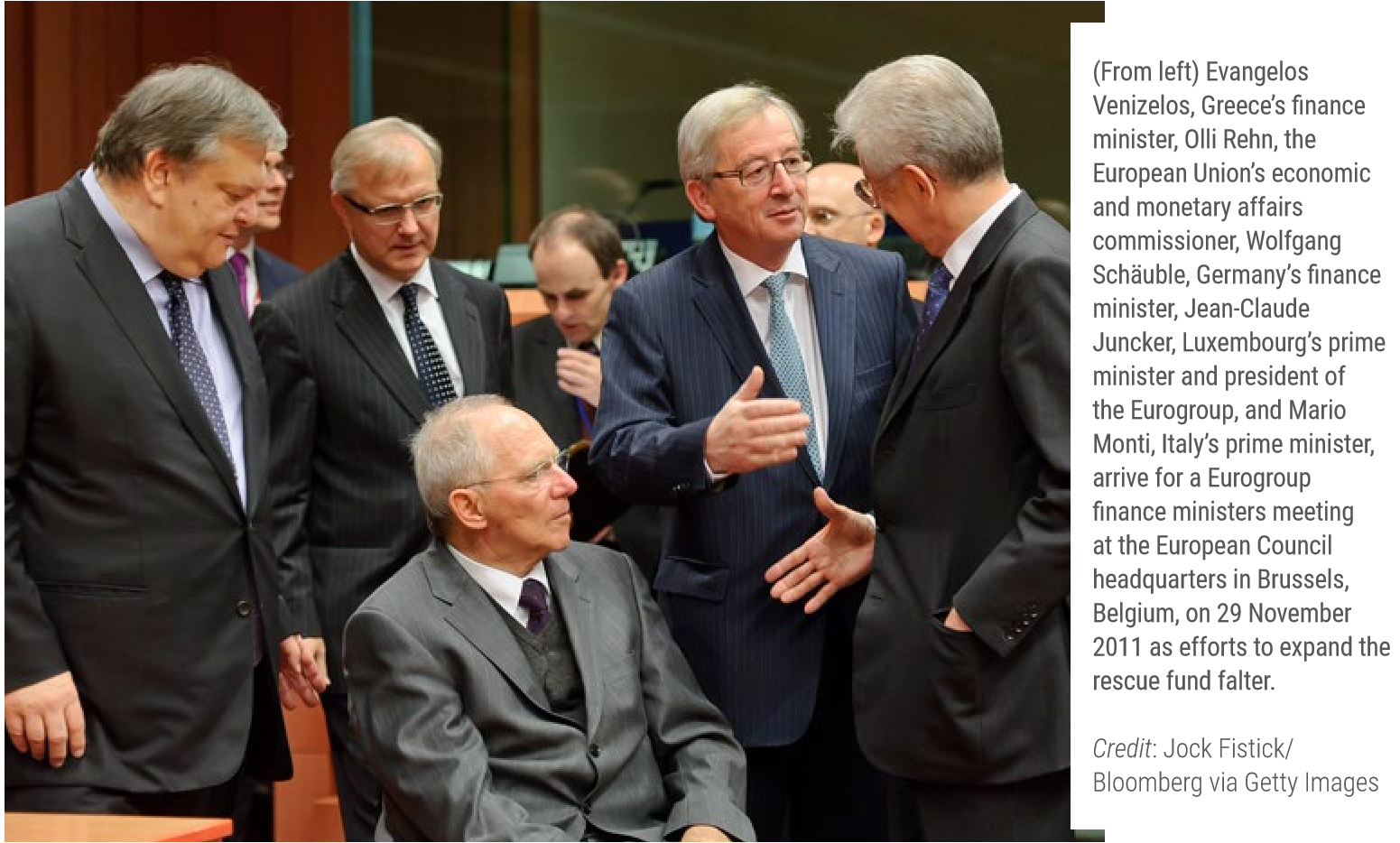

Crisis diplomacy went into overdrive in October, ranging from the traditional summit venue in Brussels to backroom discussions among key leaders at Frankfurt’s Old Opera House during a retirement ceremony for Trichet at the end of his ECB term. Trichet used the occasion to remind the euro area leaders in attendance of the commitments they had made at the 21 July summit[3].

Euro summits on 23[4] and 26 October[5] addressed what European Council President Van Rompuy called ‘the by now familiar fronts where action was needed: Greek debt sustainability, the firewall against contagion, the banking sector, economic growth’[6].

To give the EFSF more heft, the leaders decided to set up two leverage vehicles that could use smaller upfront investments to unlock far larger aid sums. Eventually these would be christened the European Sovereign Bond Protection Facility and the European Sovereign Bond Investment Facility, the latter a co-investment fund able to draw investors from around the world.

‘The leverage effect of both options will vary, depending on their specific features and market conditions, but could be up to 4 or 5,’ euro leaders said in the 26 October 2011 statement[7].

Each would require incorporating a new special purpose vehicle in Luxembourg under plans drawn up quickly by the EFSF staff. On Sunday 30 October, the EFSF’s leadership convened in a global teleconference. Regling and CFO Frankel were in Tokyo, while the EFSF’s investment advisors were in New York. Jansen, then general counsel, was spending the day with his family, while Anev Janse, the secretary general, was celebrating his 29th birthday. The party didn’t quite turn out as planned.

‘On that particular Sunday, all of a sudden we had to have a Management Board meeting,’ Anev Janse said. ‘Next to the EFSF and ESM, we had to create two other separate entities. From noon until five in the afternoon, I was on a call discussing questions like: “How do we set up these SPVs [special purpose vehicles]? How do we make this work organisationally? What are the financial structures? How do we build that into our systems?”’

As details came into focus, it became evident that the proposed up to five-fold leveraging of EFSF funds was a bridge too far. Part of the existing facility was already allocated to Ireland and Portugal, with more earmarked for Greece. In addition, it appeared that financial markets would require more participation from the EFSF to make either of the leverage plans workable. Doubling or tripling resources from the fund would be more realistic, under proposals Regling brought to a November meeting of the Eurogroup.

Both leverage options could be combined with other rescue instruments, but unlike other EFSF tools, they wouldn’t be taken over by the ESM. At their debut, however, they were an anchor point for the euro area strategy. The next summit, on 9 December 2011, vowed that they would be ‘rapidly deployed’[8], and the two vehicles were declared ready for use in February 2012[9]. But the leverage vehicles would later be dissolved, unused, even though investors had expressed interest in cooperating on their financing.

By the following year, the crisis – and the response – would move on, as centre stage shifted to more overarching decisions on economic governance and crisis management also taken at that same 9 December summit. These actions, as so often in policymaking to stabilise the euro area, reflected a compromise between the interests of creditor and programme countries by acting on two fronts, crisis prevention and crisis response.

On the governance front, the leaders toughened the euro area’s fiscal rules by committing to a new pact – eventually known as the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union[10] – that enshrined the pursuit of balanced budgets in national law and committed euro countries to closer economic coordination. While open to countries outside the euro area, the fiscal compact[11] was binding on the common currency countries and the additional EU countries that opted in. Twenty-five of the then 27 EU countries signed it in March 2012[12].

As Regling explained, the push for more effective rules meant that ‘national governments will remain in charge and accountable, responsible for their fiscal and structural reforms. However, reforms need to be better coordinated and must work better than in the past.’

The commitment to enhanced fiscal stewardship, to be made at the constitutional level in most cases[13], was intended to help countries avoid the need for a rescue programme. The pledges also paved the way for a breakthrough on crisis management tools.

Moving beyond earlier steps to increase the EFSF’s firepower, the leaders announced at the summit that the launch of the ESM – then scheduled for mid-2013 – would be brought forward by a year, to July 2012.

‘The Treaty will enter into force as soon as Member States representing 90% of the capital commitments have ratified it,’ the post-summit statement said[14]. ‘Our common objective is for the ESM to enter into force in July 2012.’

The planned speedier introduction of the ESM reshaped the course of crisis management. Although that timetable would slip by a few months, the move was still a decisive step forward that unshackled the rescue effort from the EFSF’s guarantee structure. Equally important to getting the ESM up and running fast, the euro area sped up the delivery of the ESM’s paid-in capital, starting with two tranches in 2012 and concluding with the final tranche in 2014, a full four years ahead of the original schedule[15].

Critical features of the proposed ESM were modified as well. Amid lingering concerns in the markets that Greek bond writedowns, by then under negotiation, would set a precedent for future rescues, the leaders added language to the preamble of the ESM Treaty to reassure investors that the Greek solution was ‘unique and exceptional’[16]. Only in extreme cases, the summit statement said, would the ESM pursue private sector involvement, and then solely in accordance with ‘well established IMF principles and practices.’

Summit debate then tackled the requirement for unanimous decisions on loans to programme countries – a rule written into the first draft of the ESM Treaty. There was widespread recognition that, given the vagaries of national politics, the unanimity rule could hinder rescue efforts, especially when rapid intervention was called for. At the summit, the leaders added an emergency procedure to the ESM Treaty that would allow the granting of financial assistance over the objections of some of the euro area’s smaller members.

‘To ensure that the ESM is in a position to take the necessary decisions in all circumstances, voting rules in the ESM will be changed to include an emergency procedure. The mutual agreement rule will be replaced by a qualified majority of 85%, in case the Commission and the ECB conclude that an urgent decision related to financial assistance is needed when the financial and economic sustainability of the euro area is threatened,’ the leaders said[17].

Under the 85% threshold, Germany, France, and Italy, the ESM’s three largest shareholders, continued to have blocking powers. As Schäuble, then German finance minister, explained, this was essential for him to support the ESM.

‘Given the sums involved, someone has to take responsibility for them – namely the taxpayers in the member states, including the Germans with their 27% share in the paid-in capital,’ Schäuble said. ‘Parliament is accountable to the German taxpayers, and the finance minister is in turn accountable to parliament. Nobody can relieve me of this responsibility.’

Teixeira dos Santos, then Portuguese finance minister, said the shift to the 85% rule overcame ‘a serious limitation on the decision-making process – without which member states in crisis could see the approval of the rescue programme refused or delayed. That would further worsen the situation.’

Recalling the negotiations in the Task Force on Coordinated Action, Benjamin Angel of the European Commission said it took ‘several attempts’ to remove the unanimity rule. ‘It’s potentially good to have these procedures, even though we haven’t used them,’ he said.

Taken together, the ESM overhaul reflected lessons learned from two years of crisis fighting and gave the euro area a new toolbox for curbing contagion. Nevertheless, the new clause notwithstanding, it would still be hard for the euro area to press ahead with major decisions without consensus.

‘Just think of how difficult it was for certain smaller ESM Members to justify the Greek programme to their own populations,’ said Schäuble. ‘If all Members support a programme, then at least one important precondition is met in terms of achieving political acceptance in the monetary union.’

Continue reading

[1] Finland, Statistics Finland (2011), ‘True Finns the biggest winner in the elections. Coalition party the largest party in the parliamentary elections 2011’, 29 April 2011. https://www.stat.fi/til/evaa/2011/evaa_2011_2011-04-29_tie_001_en.html

[2] Joint statement by President Herman Van Rompuy and President José Manuel Barroso on the recent political developments in Slovakia (2011), EUCO 95/11, 12 October 2011. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/125058.pdf

[3] Statement by the Heads of State or Government of the euro area and EU institutions, 21 July 2011. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/21426/20110721-statement-by-the-heads-of-state-or-government-of-the-euro-area-and-eu-institutions-en.pdf

[4] European Council, 23 October 2011, Conclusions, EUCO 52/1/11, 30 November 2011. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/125496.pdf

[5] Euro summit statement, 26 October 2011. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/125644.pdf

[6] The European Council in 2011, p. 7, January 2012. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/21347/qcao11001enc.pdf

[7] Main results of euro summit, 26 October 2011. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/125645.pdf

[8] Statement by the euro area Heads of State or Government, 9 December 2011. http://ec.europa.eu/dorie/fileDownload.do;jsessionid=zrKxL3CyxC2bUHVaut8198iEXakiK35PBFqXWiHCu9k50-L7EIBv!1583997504?docId=1099413&cardId=1099411

[9] EFSF (2012), ‘European sovereign bond protection facility launched’, Press release, 17 February 2012. https://www.esm.europa.eu/press-releases/european-sovereign-bond-protection-facility-launched

[10] Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union, 2 March 2012. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/20399/st00tscg26_en12.pdf

[11] ECB (2012), ‘Main elements of the fiscal compact’, Monthly Bulletin, March 2012, p. 101, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/mb201203_focus12.en.pdf?0ea5f8ccbeb103061ba3c778

[12] European Commission (2017), ‘The fiscal compact – taking stock’, 22 February 2017. https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/fiscal-compact-taking-stock_en

[13] European Commission (2017), ‘Report from the Commission presented under Article 8 of the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union’, C(2017) 1201 final, 22 February 2017, Appendix III, pp. 18-19. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/c20171201_en.pdf

[14] Statement by the euro area Heads of State or Government, 9 December 2011. http://ec.europa.eu/dorie/fileDownload.do;jsessionid=zrKxL3CyxC2bUHVaut8198iEXakiK35PBFqXWiHCu9k50-L7EIBv!1583997504?docId=1099413&cardId=1099411

[15] Statement of the Eurogroup, 30 March 2012. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ecofin/129381.pdf

[16] Statement by the euro area Heads of State or Government, 9 December 2011. http://ec.europa.eu/dorie/fileDownload.do;jsessionid=zrKxL3CyxC2bUHVaut8198iEXakiK35PBFqXWiHCu9k50-L7EIBv!1583997504?docId=1099413&cardId=1099411

[17] Treaty establishing the European Stability Mechanism, 11 July 2011. https://www.cvce.eu/en/obj/treaty_establishing_the_european_stability_mechanism_11_july_2011-en-cb18477d-69e4-4645-81a9-3070e02d245a.html