31. Crisis in Cyprus: ‘no negotiating power, no credibility’

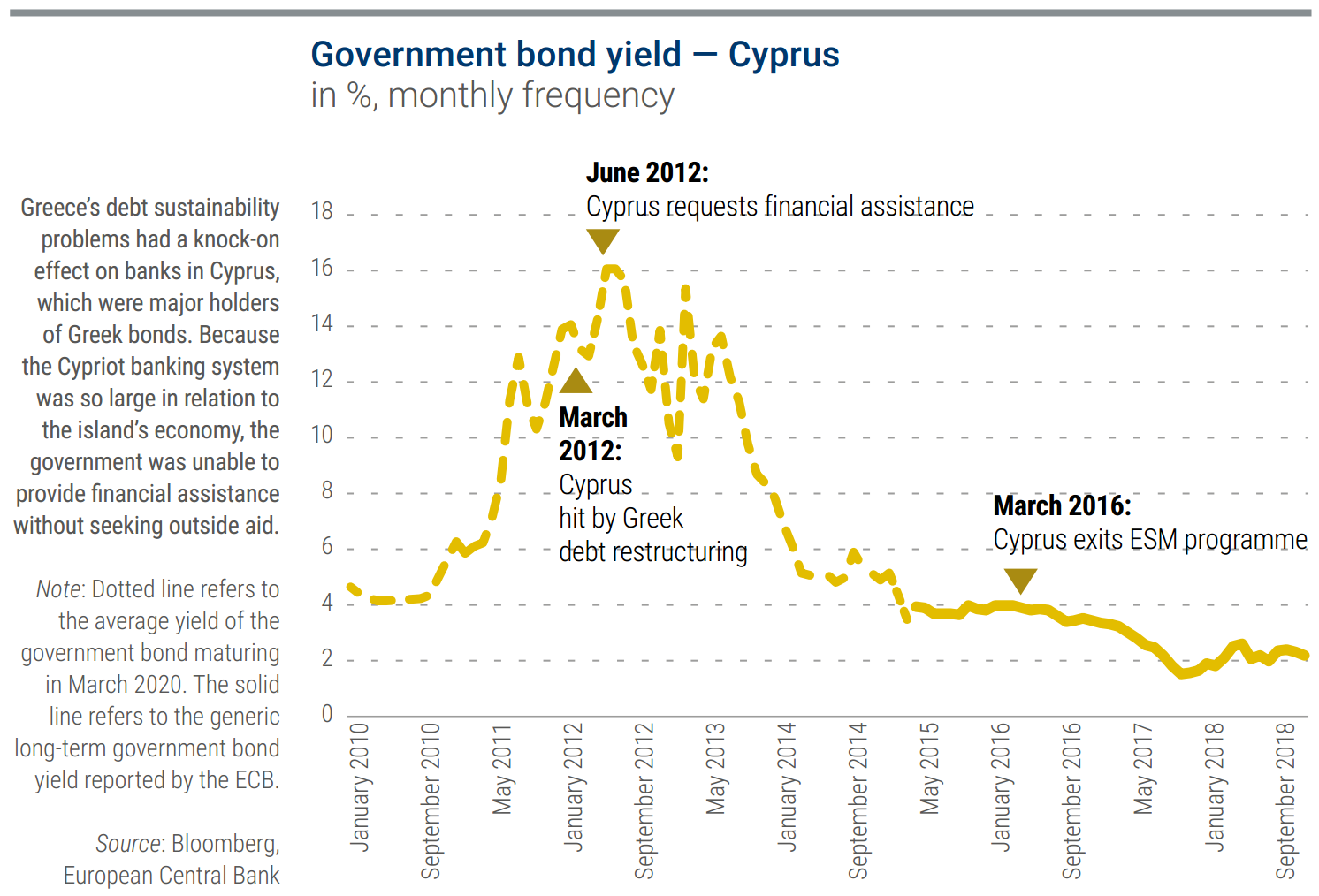

Cyprus was struggling with the broader ramifications of the crisis when the 2012 writedown of privately held Greek debt led to more than €4 billion[1] in losses for Cypriot banks, or in excess of 22% of GDP. With a banking sector that was then about six and a half times the size of the country’s economy, it was virtually impossible for Cyprus to overcome this blow on its own. Public finances also were deteriorating, with the debt-to-GDP ratio of 80% in 2012, compared with about 46% in 2008 on the eve of the crisis[2].

While harbouring reservations about the stigma and short-term economic hardship of an aid package, the government, headed by a communist president, formally sought a full macroeconomic adjustment programme with the EFSF on 25 June 2012 – the same day as Spain – but Cypriot pursuit of minimal conditions got in the way of a rapid agreement[3].

According to Michael Sarris, who would become finance minister for a short period after early 2013 elections, talks between Cyprus and what was then the troika of aid institutions focused on small issues instead of how to move forward. ‘We spent six months discussing things like a cost of living adjustment clause that the donors wanted to discontinue,’ Sarris said, describing talks in the second half of 2012. ‘In other words, details while the house was on fire.’

An agreement on conditions seemed close in November 2012, by which time the ESM was up and running. Juncker, then the outgoing president of the Eurogroup, said in early December that Cyprus was already taking the first steps to implement the draft agreement and he looked forward to its conclusion soon[4]. But by January 2013, talks had stalled. At its last meeting under Juncker, the Eurogroup announced that the programme would be delayed[5].

Discussions didn’t pick up speed until February 2013, when Nicos Anastasiades was elected president on a centrist platform[6].

When euro area finance ministers met on 4 March 2013, an accord appeared within reach. Now the Cypriot minister, Sarris outlined the government’s policy intentions. A post-Eurogroup statement praised the ‘useful’ presentation, looked ahead to the ‘swift conclusion’ of the negotiations, and pencilled in the end of March as the target for the political signoff on the programme[7].

That deadline would be met, but not in the way the Eurogroup envisaged. The final push was marked by political brinkmanship, Cypriot parliamentary opposition, the floating of Plan Bs, questions about Cyprus’s euro adherence, overtures to Moscow, and an extended bank holiday that left the 866,000-strong Cypriot population fearful for the future.

In hindsight, a Cypriot programme was inevitable.

‘The Cypriot government put us in a difficult spot by repeatedly refusing to apply for a programme,’ said Wieser, Eurogroup Working Group chairman during the crisis.‘They would have got off considerably cheaper, easier, and better if they had applied for a programme half a year earlier, or even a year earlier, as they should have.’

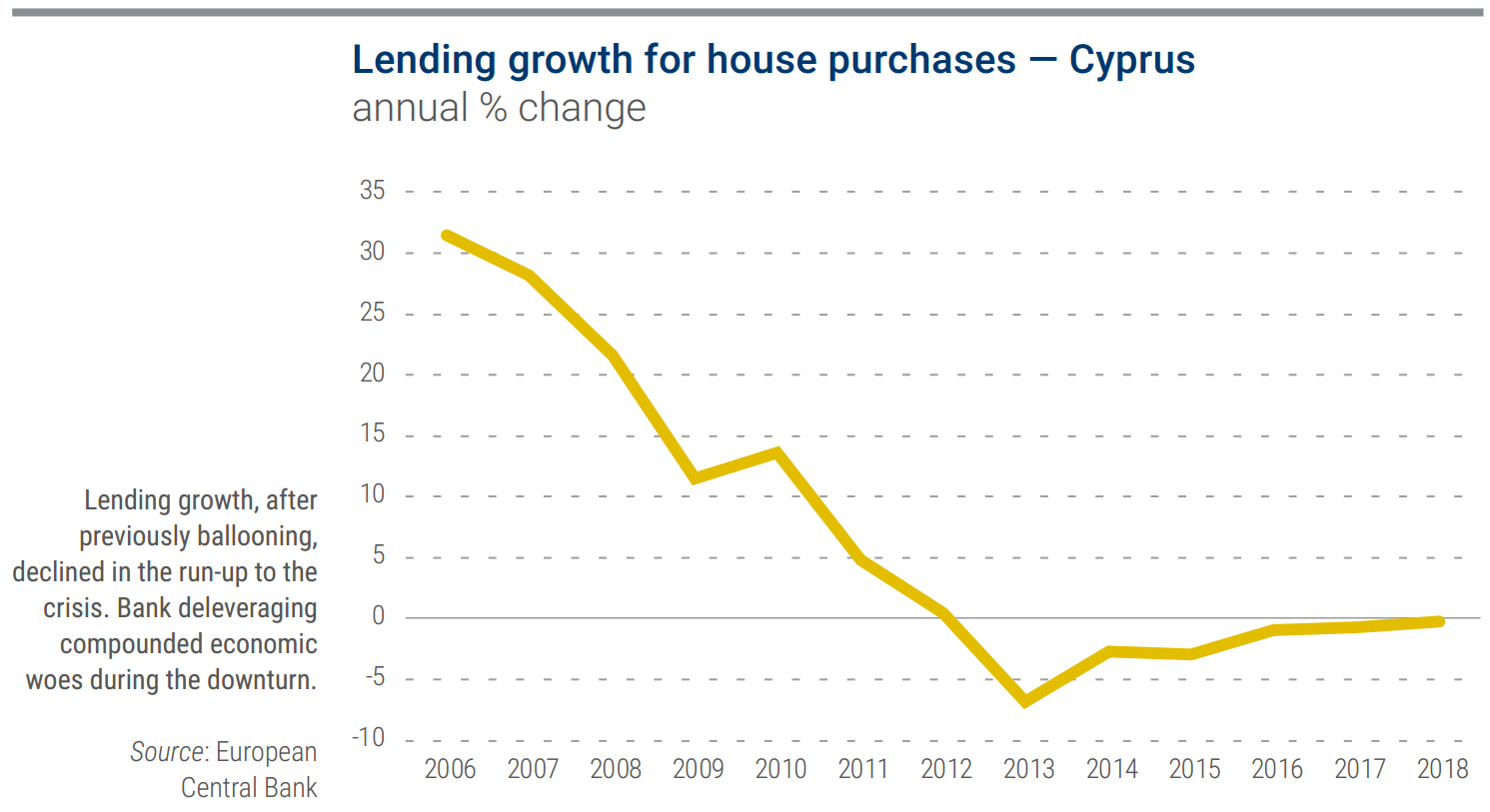

What made Cyprus different from previous programme countries was the size and skewed nature of its financial sector. Bank assets were 657% of GDP in 2012. Non-performing loans were high and would eventually reach around 50% of the loan book. Along with ordinary struggling borrowers, Cyprus had a class of strategic defaulters, who could pay but didn’t feel obliged to. ‘The legal framework was very debtor-friendly – if you didn’t pay your loan, the bank couldn’t do anything,’ said Sutt, then the ESM’s Cyprus mission chief. The haircut on Greek bonds exposed the system’s fragility.

Cyprus had tried to fix the problem on its own in May 2012, with an effort to bring in new capital of €1.8 billion for Cyprus Popular Bank, known as Laiki Bank[8]. In June, it became clear that Cyprus couldn’t raise the money privately so the government would need to provide the rest of the funds. The state aid was necessary because the bank had fallen short of meeting its minimum regulatory capital requirements as determined by the European Banking Authority, which in 2011 had started stress-testing banks across the EU.

In all, Cypriot banks were staring at a €8.9 billion shortfall in their balance sheets under an ‘adverse scenario’, according to an independent analysis that was conducted by the investment management firm PIMCO in late 2012[9].

The problems ran deeper than the banks. The European Commission had identified ‘very serious macroeconomic imbalances’ in the Cypriot economy, extending to the trade balance and public finances[10]. It called for ‘urgent economic policy attention in order to avert any adverse effects on the functioning of the economy and of Economic and Monetary Union,’ according to an in-depth review. In other words, Cyprus was seen as potentially systemic, bearing a risk of spillovers to the rest of the euro area.

This tangle of fiscal, financial, and economic deficiencies formed the backdrop for the last act in talks that would make Cyprus the fifth euro member state to receive emergency assistance. The institutions had concluded that Cyprus would need €10 billion for the banks[11], plus roughly €7 billion for general government financing[12]. But this €17 billion total was about the size of Cypriot GDP. The IMF warned that lending on that scale would render Cyprus’s debt completely unsustainable. To design a programme in which the debt could be sustainable, the Eurogroup settled on up to €10 billion in aid.

The IMF and several northern European countries pressed Cyprus to bail in bank creditors, Sarris said, to ensure that investors, debt holders – and ultimately depositors, because of the way the banks were structured – would absorb a share of the losses to cover the capital shortfall. Meanwhile, Cyprus was running out of time. Following its internal rules, the ECB was poised to cut off the Cypriot banks from their last lifeline, Eurosystem emergency liquidity assistance.

Matters came to a head at a Eurogroup meeting on 15 March 2013. Sarris went into the session under no illusions about Cyprus’s leverage. ‘We really had no negotiating power and no credibility,’ he said. With the ECB threatening to withdraw the emergency liquidity, Cyprus was faced with the choice of applying for a programme or abandoning the euro. ‘Basically, they were telling us, “Your banks would have to close,”’ Sarris recalled. ‘And they actually said, in so many words, that they couldn’t reopen.’

Cyprus’s banks were not only distinguished by their economic heft. For financing, they sold relatively few bonds, putting greater reliance on foreign depositors. As a last-ditch way to spread the pain as widely as possible, Cyprus ended up proposing a 6.75% levy on all deposits – essentially a wealth tax on everyone with a bank account[13].

Crucially, this tax would not exempt account holders covered by EU- wide deposit insurance guidelines, which were instituted in 1994 and updated in 2009 and 2010 in order to prevent bank runs and reinforce confidence in the banking system. By the time of the 2013 Cyprus aid negotiations, deposits were insured up to €100,000. Cypriot officials presented the tax as a one-off levy of 18 months of interest, since Cypriot bank accounts were returning 5% a year.

The measures being asked of Cyprus were more drastic than anything bank customers had endured in modern times. ‘But obviously that didn’t change the numbers,’ Sutt said.

In the early hours of 16 March, the Eurogroup agreed to provide up to €10 billion to Cyprus in exchange for the downsizing of the banking system, the modernisation of the financial supervisory framework, the tightening of the government’s budget, and steps to fight money laundering. A Eurogroup statement welcomed the ‘ambitious measures to ensure the stability of the financial sector’[14].

Cypriots woke up to the news that they would have less in the bank than they thought, while financial markets weighed the implications of the Eurogroup entering into the uncharted territory of forcing losses on insured depositors. When the securities exchanges opened on Monday, fears of contagion made the rounds again, with bank shares hit by concern that the Cypriot deposit tax would become a new, regularly used tool in the euro area’s arsenal and make promises of deposit insurance moot.

‘European bank shares fell more than 2% on Monday as a plan by Cyprus to seize money from bank deposits raised fears that savers elsewhere may not be safe and the euro zone may be plunged back into crisis,’ Reuters wrote on 18 March[15]. It was a reminder of how, thanks to the interconnected financial system, an island economy accounting for less than 0.2% of euro area GDP could touch off a larger crisis.

Back in Cyprus, the banks were closed and politicians up in arms over the tax on small depositors. On Tuesday, the parliament voted to reject the plan, without a single lawmaker in favour[16]. Cyprus again looked to Russia as a potential saviour. Russia had disbursed €2.5 billion to Cyprus in three tranches in 2011 and 2012, but Sarris came back empty-handed from a March 2013 trip[17]. Russia did eventually restructure its existing loans to Cyprus so they would have a longer repayment period and lower interest rates, but only after a euro area package was agreed[18].

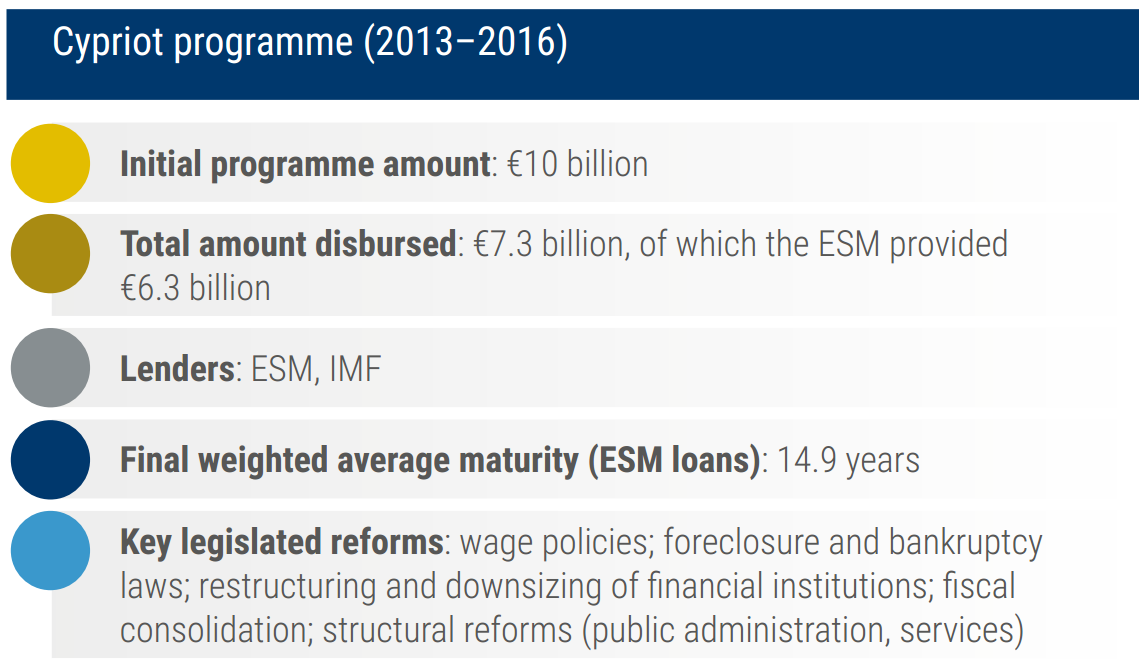

Lawmakers in Nicosia considered alternatives to the across the board bank account levy, eventually settling on a plan that spared insured deposits and shifted the burden to those holding more than €100,000. Cyprus maintained the pledges to overhaul its economy and downsize its banking sector[19]. What mattered for the Eurogroup was that the fiscal maths still worked, paving the way for a decisive policy meeting. On 25 March 2013, euro area finance ministers endorsed the revised package, with up to €10 billion in assistance during a three- year adjustment programme. It was the first full ESM programme, embracing public finance as well as banking components.

On 28 March, Cyprus imposed capital controls and began to deal with the fallout from its decisions. The agreement was finalised on 2 April. The ESM signed off on 24 April[20] on the European commitment, which would eventually be €9 billion. The IMF announced on 15 May that it would contribute €1 billion, participating on a much smaller scale than it had in past European aid packages[21].

IMF Managing Director Lagarde gave the Cypriot government credit for taking ownership of the programme, likening its commitment to that of Ireland. She praised Anastasiades for his ability to rally support at crucial moments. ‘I remember a discussion with the president, talking to colleagues and saying, you know, stop questioning, just get on and do it,’ Lagarde said.

As part of the agreement, Cypriot banks sold their Greek branches to Piraeus Bank ahead of the capital controls, ensuring those offices could reopen and Greek depositors wouldn’t be touched by the limits imposed. The capital controls won the cautious blessing of the euro area, because of the ‘unique and exceptional situation of Cyprus’s financial sector and to allow for a swift reopening of the banks’[22]. As long as the measures were temporary, proportionate and non- discriminatory, in line with EU treaties, they could go ahead.

Cyprus even managed to restructure some of its government debt as part of efforts to get its financial picture under control. In June 2013, it swapped some of its local bonds for longer-term bonds in a bid to ease immediate liquidity pressures. The move put Cyprus briefly into ‘selective default’ from a credit rating standpoint, as analysts at Standard & Poor’s judged the new bonds to be on less favourable terms for Cyprus’s investors[23].

Although it upset markets at the time, the Cyprus solution was also a game changer in bank resolution. The notion of an upfront bail-in of all bank creditors, including senior creditors if necessary, was not yet customary in the EU and only junior creditors had previously been required to take losses. The Cypriot programme was in its first year when, in December 2013, the European Parliament and representatives of national governments struck an agreement on the bank recovery and resolution directive[24], which spells out how investors are in line to take losses when a bank fails. The move to tap senior bank creditors in Cyprus was part of significant changes in the banking landscape[25].

Today it is clear that the Cypriot programme set a new precedent for handling a large and troubled banking sector by de-emphasising the taxpayer-funded rescues that had been the traditional approach in Europe and elsewhere. In Spain, junior bondholders took losses but senior creditors were spared. However, in Cyprus, the banks had little junior debt and the numbers didn’t add up unless senior creditors contributed.

The ESM was still an embryonic organisation, sending a two-or three-person team to the Cyprus talks. While outnumbered by representatives of the other institutions, the ESM delegation brought a mix of public and private sector experience, as well as a broad spectrum of understanding of the connections between banks, finance, and the debt repayment profile.

It helped that the ESM had established itself based on its work in other countries. This created a virtuous circle: because the ESM had gained respect from its work with the other institutions and local authorities, it received better cooperation from its partners. And, with the additional information that close cooperation can provide, its own contributions improved further.

‘With the ESM in the picture, the institutional roles changed and that facilitated the access,’ said ESM Chief Economist Strauch. ‘It worked relatively well in Cyprus, pretty much from the start.’

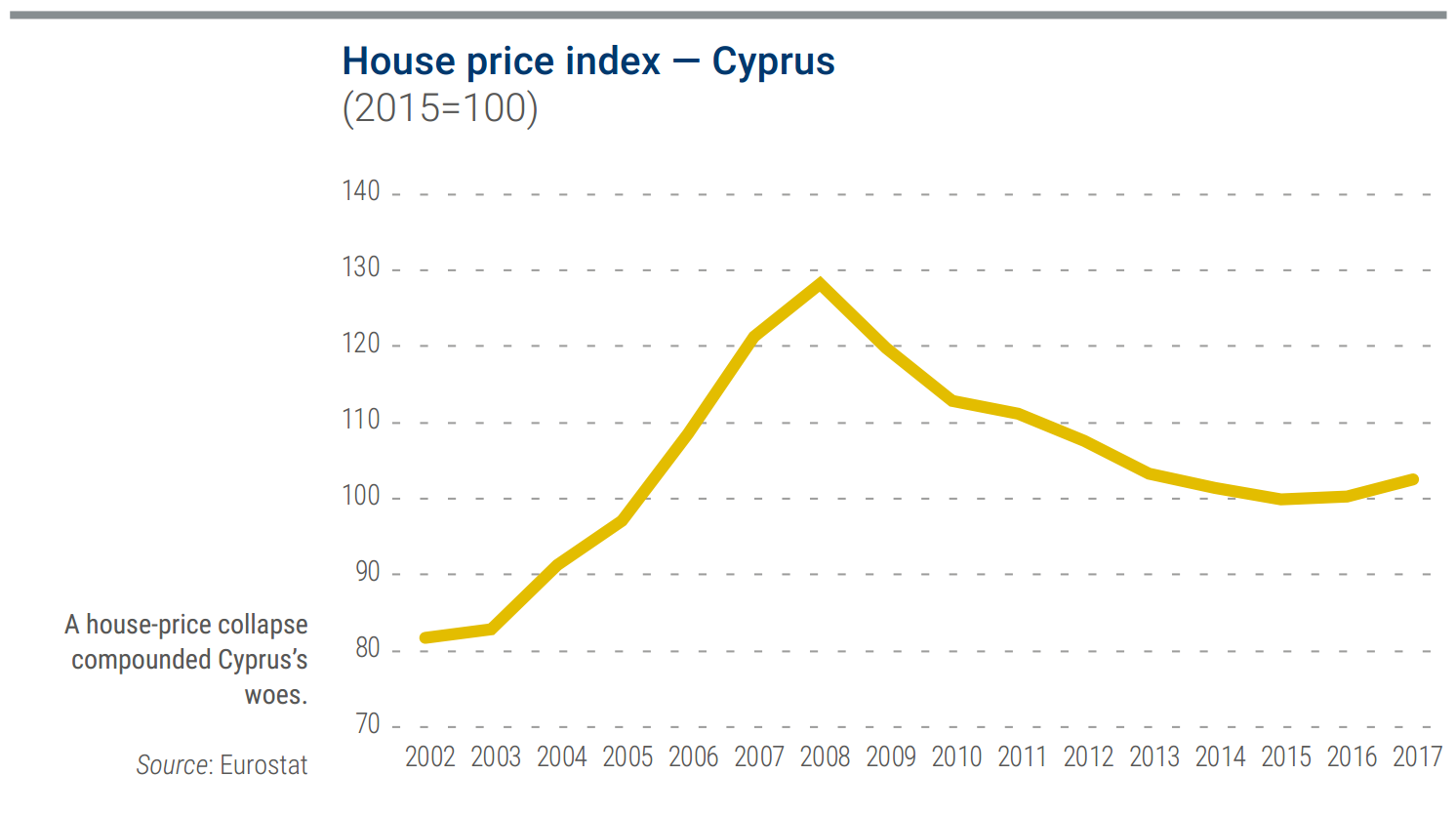

Cyprus tackled the task of whittling away at the rapidly accumulating debt. Once Cyprus was carrying out its programme, real house prices rose, a sign that homeowners were benefiting from the economic reforms. Its debt-to-GDP ratio peaked at 107.5%, a better outcome than expected, and the country progressed in overhauling its banks.

Fresh capital for banks, some of which came from the aid programme, brought a first glimmer of confidence. However, some of the efforts to stabilise the financial sector have proven tricky. The programme included €1.5 billion in capital to the country’s Cooperative Central Bank, but the bank later required another infusion of state aid after an ECB review found it wasn’t doing enough to manage non-performing loans[26]. The cooperative bank then came under increased scrutiny until 2018, when it was split up[27]. Parts of the bank were sold to a domestic competitor, while in particular the non-performing loans remained in a state-owned asset management company.

In the end, the capital controls did less damage than expected, because their implementation varied across different types of transactions in an attempt to minimise payment system disruptions and ensure the execution of transactions essential for the real economy[28].

‘One of the reasons why the capital controls did not disrupt the economy was that the programme included an efficient roadmap to remove them step by step once clear milestones in the programme were reached,’ said Paolo Fioretti, the ESM’s country coordinator for Cyprus. ‘A clear time horizon increased the commitment of the government in implementing related necessary measures and gave people more confidence that the controls would be transitory.’

Overall, the programme strengthened the banks while also reining them in. ‘In the end, the banking sector benefited too,’ said Sutt, a veteran of the IMF and the Estonian Central Bank. Cyprus Popular Bank was shut when its troubles became too big to fix. Meanwhile, the largest Cypriot bank became de facto foreign controlled, as did the third largest, bringing new incentives for the banks to improve governance, work better with the government, and lend in a way that helps the overall economy. ‘The shareholder structure changed dramatically. It helped to change the governance and the links between the banks and the entrepreneurs, and the politics,’ Sutt said. ‘In the end, I think it’s a positive for a country. But these exercises are, at the time, never easy in terms of implementation.’

The programme in Cyprus benefited from strong cooperation with local authorities, once it was finally underway. ‘In March of 2013, Cyprus was in a difficult position. Most of the adjustment efforts had to come from the Cypriot population. Now, we see that the approach has brought good results,’ Fioretti said.

Cyprus lifted all external capital controls on 6 April 2015[29]. In March 2016, Cyprus exited its programme on schedule, although it chose to leave €2.7 billion of the initial envelope unspent – in part because it was unable to meet a few of its last programme conditions by the time of the exit, and in part because financing needs turned out to be lower than initially estimated.

‘Cyprus has managed to restore economic growth and repair public finances much faster than expected,’ said Juncker, now the Commission president.‘Overall, the experience in Cyprus confirms what we have seen in other programme countries: the strategy of providing loans to a country in a deep crisis in exchange for economic policy reforms is one that works.’

Continue reading

[1] IMF (2013), ‘Cyprus: Letter of intent, memorandum of economic and financial policies, and technical memorandum of understanding’, 29 April 2013, p. 3. https://www.imf.org/external/np/loi/2013/cyp/042913.pdf; Demetriades, P. (2017) A Diary of the Euro Crisis in Cyprus. Lessons for Bank Recovery and Resolution, Switzerland, Palgrave MacMillan

[2] Eurostat (n.d.), ‘General government gross debt – % of GDP and million EUR’. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=sdg_17_40&plugin=1

[3] Statement by the president of the Eurogroup, 25 June 2012. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ecofin/131195.pdf

[4] Statement by the president of the Eurogroup, 3 December 2012. https://www.eerstekamer.nl/eu/overig/20121210/statement_by_the_president_of_the/document

[5] European Commission (2013), ‘Speech: Vice-President Rehn’s remarks at the Eurogroup Press Conference’, 21 January 2013. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-13-41_en.htm

[6] Cyprus, Ministry of the Interior (2013), ‘Presidential run-off elections 2013: Official results’, February 2013. http://results.elections.moi.gov.cy/English/PRESIDENTIAL__EPANALIPTIKI_EKLOGI_ELECTIONS_2013/Islandwide

[7] Eurogroup statement on Cyprus, 4 March 2013. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ecofin/135809.pdf

[8] Cyprus, Central Bank of Cyprus (2013), ‘Rescue programme for Laiki Bank’, Announcement, 30 March 2013. https://www.centralbank.cy/en/announcements/30-03-2013; European Commission (2012), ‘State aid: Commission temporarily approves rescue recapitalisation of Cyprus Popular Bank’, Press release, 13 September 2012. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-12-958_en.htm

[9] PIMCO (2013), ‘Independent due diligence of the banking system of Cyprus’, Report, PIMCO Europe Ltd, London, March 2013. https://ftalphaville-cdn.ft.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/reportasws.pdf.pdf

[10] European Commission (2012), ‘Following in-depth reviews, Commission calls on Member States to tackle macroeconomic imbalances’, Memo, 30 May 2012. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-12-388_en.htm

[11] Reuters (2012), ‘Cyprus bailout eyes up to 10 billion euros for banks: Central bank’, 30 November 2012. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cyprus-bailout-banks/cyprus-bailout-eyes-up-to-10-billion-euros-for-banks-central-bank-idUSBRE8AT0I220121130

[12] European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2013), ‘The Economic Adjustment Programme for Cyprus’, European Economy Occasional Papers 149, May 2013. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2013/pdf/ocp149_en.pdf

[13] Economist (2013), ‘The Cyprus bail-in – A bungled bank raid’, 23 March 2013. https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2013/03/23/a-bungled-bank-raid

[14] Statement by the Eurogroup on Cyprus, 16 March 2013. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ecofin/136190.pdf

[15] Reuters (2013), ‘European bank stocks drop on Cyprus contagion fear’, 18 March 2013. https://uk.reuters.com/article/us-eurozone-cyprus-banks-idUKBRE92H0ET20130318

[16] Reuters (2013), ‘Cyprus lawmakers reject bank tax; bailout in disarray’, 19 March 2013. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cyprus-parliament/cyprus-lawmakers-reject-bank-tax-bailout-in-disarray-idUSBRE92G03I20130319?feedType=RSS; Bloomberg (2013), ‘Cyprus loan request spurned by Russia in Moscow: Sarris’, 21 March 2013. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-03-21/cyprus-said-to-seek-…

[17] Reuters (2013), ‘Cyprus seeks Russia investment, loan extension: Finance minister’, 21 March 2013. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eurozone-russia-sarris/cyprus-seeks-russia-investment-loan-extension-finance-minister-idUSBRE92K09220130321

[18] European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs (2013), ‘The Economic Adjustment Programme for Cyprus’, European Economy Occasional Papers 149, May 2013, p. 107. http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/occasional_paper/2013/pdf/ocp149_en.pdf

[19] Eurogroup statement on Cyprus, 25 March 2013.

[20] ESM (2013), ‘ESM Board of Governors grants stability support to Cyprus’, Press release, 24 April 2013. https://www.esm.europa.eu/press-releases/esm-board-governors-grants-stability-support-cyprus

[21] IMF (2013), ‘IMF executive board approves €1 billion arrangement under extended fund facility for Cyprus’, Press release, 15 May 2013. http://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/14/01/49/pr13175

[22] Eurogroup statement on Cyprus, Statement, 25 March 2013.

[23] S&P Global (2013), ‘Research update: Cyprus ratings lowered to “SD” following announced exchange offer on several local law bonds’, 28 June 2013. https://www.standardandpoors.com/en_US/web/guest/article/-/view/sourceId/8086197

[24] European Parliament (2013), ‘Deal reached on bank “bail-in directive”’, Press release, 12 December 2013. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20131212IPR30702/deal-reached-on-bank-bail-in-directive

[25] ‘Directive 2014/59/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 establishing a framework for the recovery and resolution of credit institutions and investment firms and amending Council Directive 82/891/EEC, and Directives 2001/24/EC, 2002/47/EC, 2004/25/EC, 2005/56/EC, 2007/36/EC, 2011/35/EU, 2012/30/EU and 2013/36/EU, and Regulations (EU) No 1093/2010 and (EU) No 648/2012, of the European Parliament and of the Council text with EEA relevance’, L173/190, 12 June 2014. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0059

[26] European Commission (2015), ‘State aid: Commission approves additional aid for Cypriot cooperative banks on the basis of an amended restructuring plan’, Press release, 18 December 2015. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-6365_en.htm

[27] Central Bank of Cyprus (2018), ‘Withdrawal of licence of Cyprus Cooperative Bank’, 5 September 2018. https://www.centralbank.cy/en/announcements/withdrawal-of-licence-of-cyprus-cooperative-bank

[28] IMF (2013), ‘Cyprus: Letter of intent, memorandum of economic and financial policies, and technical memorandum of understanding,’ 29 April 2013, p. 3. https://www.imf.org/external/np/loi/2013/cyp/042913.pdf

[29] European Commission (2015), ‘The Economic Adjustment Programme, Cyprus: 6th Review – spring 2015’, European Economy Institutional paper 004, Spring 2015, p. 23. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/file_import/ip007_en_2.pdf